Opposing forces during Rhodesian Bush War - ideology, strength and casualties; and impact on civilians.

The ideology behind the conflict and major timelines

During a recent review of the conflict, academic and one of the early White Nationalists, Professor Terry Ranger stated “It is too simplistic to interpret Rhodesian history in binary terms - white versus black; or colonialism versus anti-colonialism.” In understanding the course and dynamic of the conflict in Rhodesia, it is crucial to appreciate the impact of the Cold War upon the perceptions of Rhodesian rulers and their responses; and the actions of the various nationalist and liberation movements themselves, who looked for external assistance and support in their mission. The influence within the region of South Africa on the one hand and that of the Frontline States on the other contributed to varying degrees.

The Rhodesian rulers regarded that domestic African opposition and guerrilla  warfare were the product of an external, communist threat - rather than seeing it as home-grown resistance to white rule. Opposition white liberals did themselves no favours by failing to produce a coherent, consistent alternative so the Rhodesian Front (RF) party retained political control. The RF had a surprising and narrow win of 54.9% in 1962 under Winston Field who was replaced as party leader and Prime Minister by Ian Smith two years later (photo on the left). In subsequent elections RF secured a minimum of 76% of the votes.

warfare were the product of an external, communist threat - rather than seeing it as home-grown resistance to white rule. Opposition white liberals did themselves no favours by failing to produce a coherent, consistent alternative so the Rhodesian Front (RF) party retained political control. The RF had a surprising and narrow win of 54.9% in 1962 under Winston Field who was replaced as party leader and Prime Minister by Ian Smith two years later (photo on the left). In subsequent elections RF secured a minimum of 76% of the votes.

The government and supporting civil service, and wider opinion within the country, believed that they were building a stable, prosperous multi-racial society, founded on sustained economic growth and the gradual transference of skills. This reform was not swift enough for the radicalized African nationalists.

Reports by refugees that were fleeing south from the Congo Crisis about attacks on white officers and civilians, looting and the rape of white women that occurred after independence was granted by Belgium in June 1960 - without a period of transition - contributed to the widespread belief among whites in Rhodesia that nationalists were not ready to govern. Tens of thousands of African lives were lost in the Congo over the next five years.

In Rhodesia from 1966, and especially from 1972, the rulers adopted a military response to the insurgency due to the loss of lives of innocent people in the rural areas. The police response to criminal acts was through the civil courts.

Pressure was exerted by the Organization for African Unity (OAU) and the host countries (Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia) of the forces belonging to both Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU) and Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) that were operating from their territories, to  cooperate in the political sphere. This led to the façade of the Patriotic Front being formed in 1976 that was a nominal political alliance between the two, brokered for the Geneva Conference. However, the discord persisted between ZAPU’s military wing Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA or ZPRA) and ZANU’s Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA).

cooperate in the political sphere. This led to the façade of the Patriotic Front being formed in 1976 that was a nominal political alliance between the two, brokered for the Geneva Conference. However, the discord persisted between ZAPU’s military wing Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA or ZPRA) and ZANU’s Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA).

The emphasis by Rhodesia remained on the military sphere, as the state became fixated upon “body counts” of eliminated insurgents as the measure of success. Communiques referred to them as Communist Terrorists (CT). Notebooks taken from political officers attached to insurgent groups, as well as uniforms and weaponry from the Eastern bloc confirmed Russian and Chinese sponsorship and ideology. This was further substantiated by the apprehension of a KGB General by Rhodesian troops during the pre-emptive strike to the ZANLA operated base at “New Farm” at Chimoio, Mozambique in November 1977.

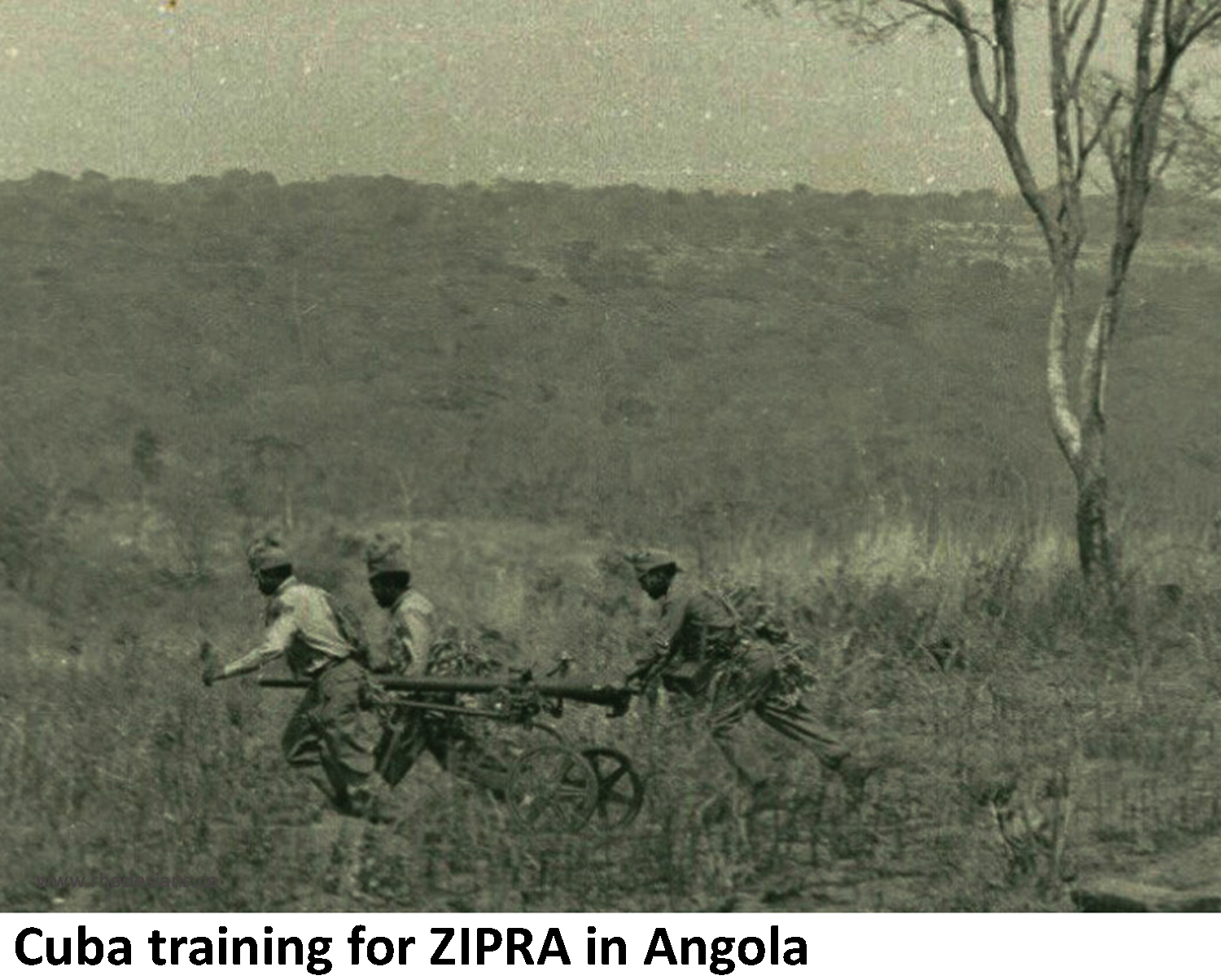

ZAPU’s strategy shifted to plans for conventional warfare in 1977–79, backed by Soviet logistical guidance and Cuban training of 6,000 ZIPRA in batches of 2,000 from 1977 onwards at Boma and Lupea (formerly Vila Luso) in eastern Angola.

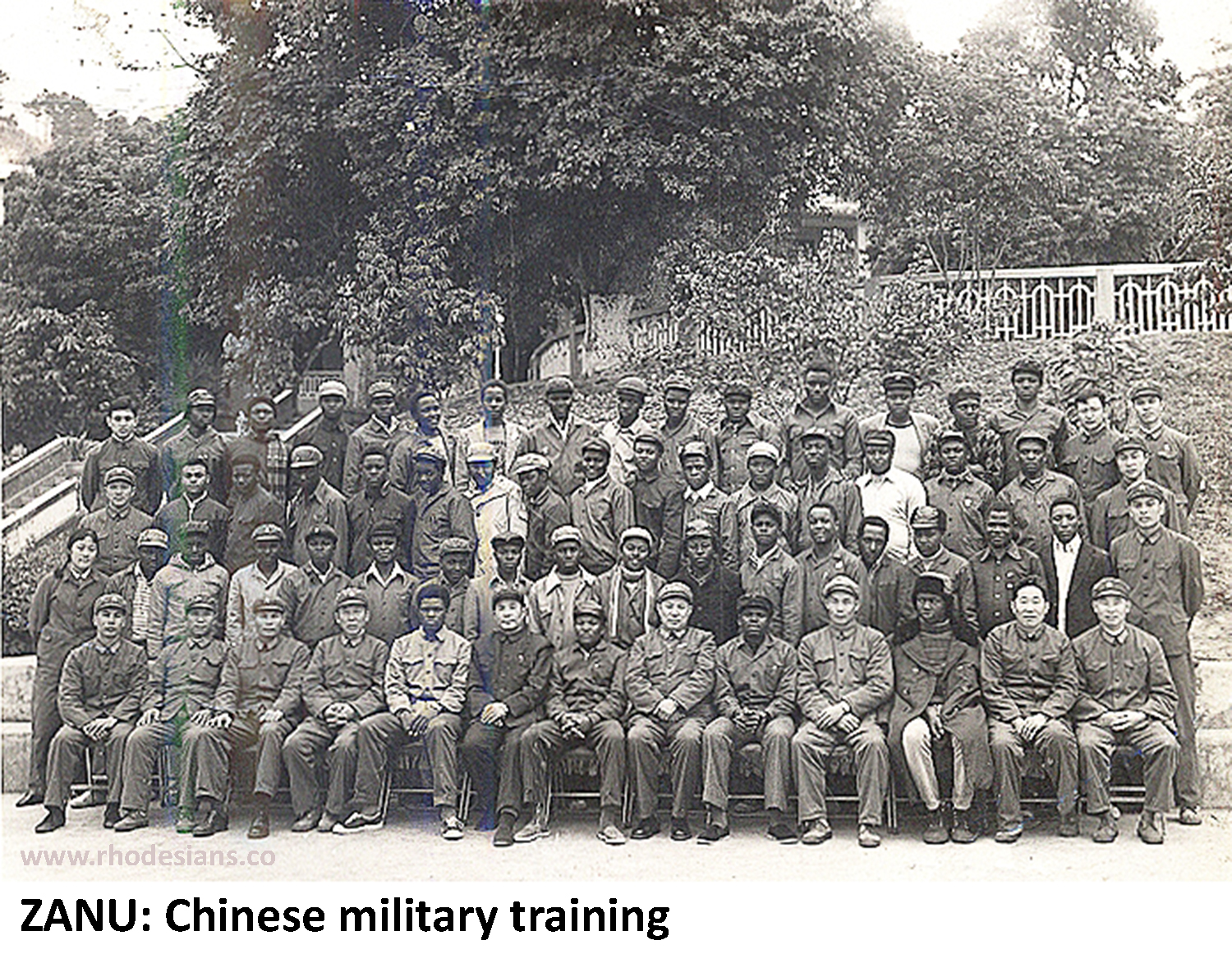

Concurrently, the ZANU army, based principally in Mozambique, relied increasingly upon the People’s Republic of China, and Maoist strategies of mobilization and revolutionary warfare. By 1976, Ethiopia, Yugoslavia and Rumania were also offering more training facilities to ZANU.

After the 1976 Kissinger Initiative then the 1977 Owen/Vance Proposals were both rejected by the Rhodesians and the Nationalist groups, there was a perceptible shift in South Africa towards the Rhodesian government’s plan for the transition to majority rule through an internal settlement that marginalized the Patriotic Front. While this was progressing, Amnesty International warned in an annual report that there could be “perhaps a civil war between rival nationalist organisations”.

Subsequently the Rhodesian government announced that agreement had been reached between  White leader, Ian Smith, with moderate African nationalist parties that were not involved in the Communist insurgency. They were the UANC headed by Bishop Abel Muzorewa, a ZANU splinter group that was led by Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole and domestic Chief Jeremiah Chirau. (In 1969 Sithole had renounced violence so had fallen out as a candidate for presidency of ZANU. Muzorewa lost credibility when he criticized the formation of ZIPA in late 1975.)

White leader, Ian Smith, with moderate African nationalist parties that were not involved in the Communist insurgency. They were the UANC headed by Bishop Abel Muzorewa, a ZANU splinter group that was led by Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole and domestic Chief Jeremiah Chirau. (In 1969 Sithole had renounced violence so had fallen out as a candidate for presidency of ZANU. Muzorewa lost credibility when he criticized the formation of ZIPA in late 1975.)

This internal settlement led to multiracial elections being held in June 1979. Muzorewa, the electoral victor, took office as the country's first black Prime Minister at the head of a coalition Cabinet. 64.5% of the electorate had voted, and Muzorewa had won an absolute majority. The new Thatcher government in Britain was more favourably disposed toward Muzorewa’s government than the Labour party had been, but the USA Carter Administration retained economic sanctions despite a US Senate resolution declaring that the May 1979 elections were free and fair, and that conditions for black majority rule had been met. The African nations threatened a trade boycott if the UK recognized the Muzorewa government. The Thatcher government rejected the new administration.

The civil war continued with ongoing armed resistance from both Soviet- and Chinese-backed insurgents. Support for the Rhodesian security forces was costing the South African government £1m a day so South Africans put new pressure on Muzorewa and Smith to attend fresh negotiations. A brutal round of external military raids by Muzorewa renewed pressure from the neighbouring Mozambique and Zambia hosts on ZANU and ZAPU to participate too. Negotiations commenced at Lancaster House in December 1979. The UK suspended the constitution and vested full executive and legislative powers in a new Governor, Lord Soames, who oversaw a ‘ceasefire’.

The ceasefire only existed on paper as the loss of life by combatants and civilians continued into 1980.

Despite cases of intimidation in the build up to and during the 1980 election that was blatant to anyone resident there, the conclusion was reached by the British that the outcome had not been compromised. The British government under Callaghan had covered up Mugabe's ZANLA atrocities against British missionaries that had been murdered in Rhodesia to protect his image in the build up to negotiations that ultimately led to the Lancaster House Agreement. Nkomo had sealed his fate when he gloated during an interview after his force ZIPRA had shot the first civilian aircraft with a heat seeking missile that prompted political analysts at that time started to consider Nkomo to be more of a threat to stability post-Independence than Mugabe.

As the countdown to Independence was ticking, the commander of the Zimbabwe Rhodesia army voiced his displeasure in a letter to the British Prime Minister after the three days of voting. Walls stated that the governor Load Soames had failed to implement the solemn promise given by Margaret Thatcher and Lord Carrington to him and the Zimbabwe-Rhodesian government delegation despite the political sacrifice that they had made by conceeding power at Lancaster. The despair that resulted from indifference and inadequacy by Lord Soames resulted in "intimidation, breaches of the ceasefire, and sheer terror accepted pathetically by your representatives". Such breaches were considered to have made the most inevitable result to be a victory by Mugabe. General Walls proposed scenarios depending on three outcomes that could result from the election in a letter that he had allegedly writtien to the Bristish Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher on 1st March 1980.

The British pressed on and the votes were counted from the election that had been marred by intimidation. In a ceremony Lord Soames and Prince Charles lowered the Union Jack and Robert Gabriel Mugabe became the Prime Minister of Zimbabwe on 18th April 1980.

History of African Nationalism

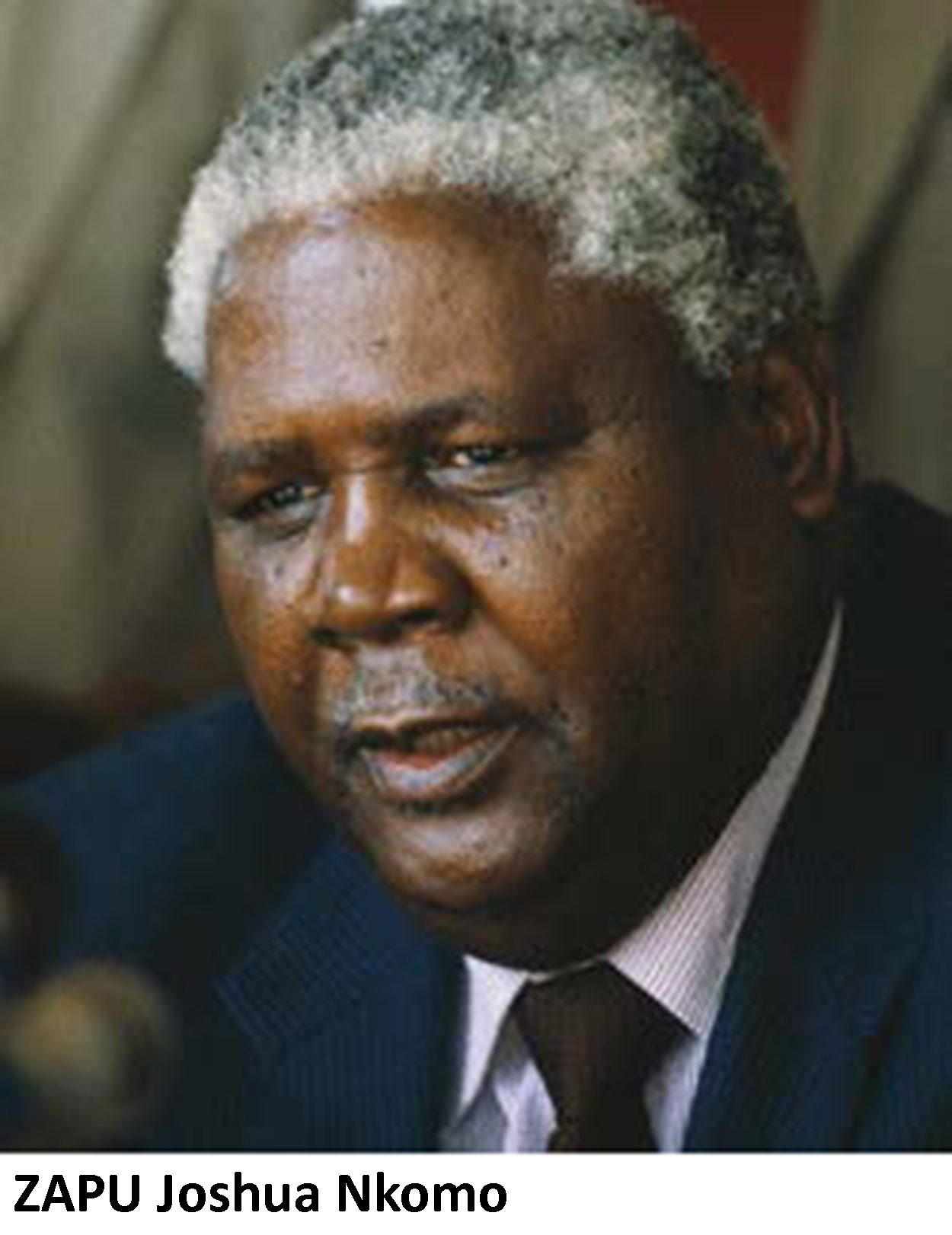

There are several names and parties that are associated with Nationalism. Joshua Nkomo  was amongst the first from the era that used the slogan ‘One Man, One Vote’. He stood for the Federal seat for Matabeleland in the January 1954 election without success but became president of the reformed Southern Rhodesia African National Congress (SRANC and then ANC) in 1957 that had absorbed the Youth League under James Chikerema and George Nyandoro. After being banned, it then became the National Democratic Party (NDP). In July 1960, protests in Bulawayo escalated into urban unrest. Civil unrest then spread throughout the country until more rioters were shot during protests. In 1961, Robert Mugabe had spearheaded a cultural revival programme which saw ordinary members of the NDP being asked to reject European culture in favour of traditional African practices. This had been initiated by white nationalist Terence Ranger’s public removal of his shoes. A series of protests at the start of December saw more arrests. Subsequent riots resulted in one death, more injuries and detentions. After banning in December, NDP was renamed the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU).

was amongst the first from the era that used the slogan ‘One Man, One Vote’. He stood for the Federal seat for Matabeleland in the January 1954 election without success but became president of the reformed Southern Rhodesia African National Congress (SRANC and then ANC) in 1957 that had absorbed the Youth League under James Chikerema and George Nyandoro. After being banned, it then became the National Democratic Party (NDP). In July 1960, protests in Bulawayo escalated into urban unrest. Civil unrest then spread throughout the country until more rioters were shot during protests. In 1961, Robert Mugabe had spearheaded a cultural revival programme which saw ordinary members of the NDP being asked to reject European culture in favour of traditional African practices. This had been initiated by white nationalist Terence Ranger’s public removal of his shoes. A series of protests at the start of December saw more arrests. Subsequent riots resulted in one death, more injuries and detentions. After banning in December, NDP was renamed the Zimbabwe African Peoples Union (ZAPU).

In August 1962, ZAPU's executive agreed to procure weapons in Cairo for the struggle. This was a watershed moment and the party was promptly banned. Prime Minister Edgar Whitehead from the liberal United Federal Party said: “ZAPU was not banned because of its political opinions. It was banned because its members adopted terrorism as a weapon to force people to support its cause ... What I will not tolerate is a Party which ... communicates with foreign powers with a view to overthrowing the legitimate government of the country; stirs up racial feelings and encourages hostility between the races.”

The potential independence of Southern Rhodesia was being debated between the  British and conservative Winston Field (who had replaced Whitehead) the Rhodesia leader at the Victoria Falls Conference in June/July 1963. Conflicting visions for the future were generating tensions within the nationalist movement. Over the course of four weeks, two factions of ZAPU moved against each other in a series of coups and counter-coups. Since the flight of the ZAPU executive from the country in February 1963, the two 'elders' (Joshua Nkomo and Ndabaningi Sithole) found themselves in a struggle for power amid attempts to draw members of the executive with common ideals to their camps.

British and conservative Winston Field (who had replaced Whitehead) the Rhodesia leader at the Victoria Falls Conference in June/July 1963. Conflicting visions for the future were generating tensions within the nationalist movement. Over the course of four weeks, two factions of ZAPU moved against each other in a series of coups and counter-coups. Since the flight of the ZAPU executive from the country in February 1963, the two 'elders' (Joshua Nkomo and Ndabaningi Sithole) found themselves in a struggle for power amid attempts to draw members of the executive with common ideals to their camps.

The split between Nkomo and Sithole became irrevocable by the end of July, despite the failed attempts by Todd and Clutton-Brock (White Nationalists) to heal the rift. Sithole had drawn to his side Mugabe and others as well as a dozen other leading nationalists.

The official announcement of a new African party named the Zimbabwean African National Union (ZANU) was made on 8 August 1963.

As a consequence of this split, there were two competing parties that sought the support of sponsors that were competing politically yet ideologically similar.

As the Cold War was raging at this time, the Soviet Union sought to weaken Western influence in the region, and to promote the emergence of radical black governments in Rhodesia, South West Africa, South Africa, and the former Portuguese colonies was seen as a means to increase Soviet influence in the region. Lastly, the Sino-Soviet split and Chinese support for a variety of African liberation movements forced the Soviets’ hand, as the Chinese presence, in addition to challenging the Soviet position as the leader of the global Communist movement, also threatened Soviet efforts to be seen as the chief benefactor of liberation and revolutionary movements throughout Africa.

The Soviets adopted a flexible approach to Third World liberation movements. Instead of  only supporting leaders who were committed Marxist-Leninists, Khrushchev acknowledged the emergence of a nonaligned group of leaders who, by virtue of their emphasis on national liberation and anti-imperialism, were worthy of Soviet aid and support. As long as they were genuinely “anti-imperialist” they merited Soviet support. Thus, it was not by coincidence that the first contacts between Joshua Nkomo, the leader of ZAPU, and Soviet authorities occurred while Khrushchev was leader of the Soviet Union. This appears to have occurred in late 1959 or early 1960, when Nkomo first requested aid from the Soviet embassy in London. In 1961 the Soviet government decided to use the KGB in a worldwide campaign to support national liberation movements against Western interests. At the same time, Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai (who subsequently went on to become Leader) declared that Africa was “ripe for revolution.”

China’s support to African liberation movements was largely rhetorical and symbolic at that time. It lacked the financial resources to fully support ZANU and other African liberation movements, and the weapons it provided were seen as inferior relative to Soviet military aid. Yet for Africans, the Peoples’ Republic of China served as a model for what can be achieved by a backward agrarian economy in a relatively short period. China did not rule out aiding ZAPU in the early 1960s, but considered that the sponsorship of ZANU was perhaps a better fit because ZANU was not tainted by the Soviet influence that had been instigated by Nkomo.

The table below shows the alignment of Soviet and Chinese aid to liberation factions across southern Africa:

only supporting leaders who were committed Marxist-Leninists, Khrushchev acknowledged the emergence of a nonaligned group of leaders who, by virtue of their emphasis on national liberation and anti-imperialism, were worthy of Soviet aid and support. As long as they were genuinely “anti-imperialist” they merited Soviet support. Thus, it was not by coincidence that the first contacts between Joshua Nkomo, the leader of ZAPU, and Soviet authorities occurred while Khrushchev was leader of the Soviet Union. This appears to have occurred in late 1959 or early 1960, when Nkomo first requested aid from the Soviet embassy in London. In 1961 the Soviet government decided to use the KGB in a worldwide campaign to support national liberation movements against Western interests. At the same time, Chinese Foreign Minister Chou Enlai (who subsequently went on to become Leader) declared that Africa was “ripe for revolution.”

China’s support to African liberation movements was largely rhetorical and symbolic at that time. It lacked the financial resources to fully support ZANU and other African liberation movements, and the weapons it provided were seen as inferior relative to Soviet military aid. Yet for Africans, the Peoples’ Republic of China served as a model for what can be achieved by a backward agrarian economy in a relatively short period. China did not rule out aiding ZAPU in the early 1960s, but considered that the sponsorship of ZANU was perhaps a better fit because ZANU was not tainted by the Soviet influence that had been instigated by Nkomo.

The table below shows the alignment of Soviet and Chinese aid to liberation factions across southern Africa:

| Country | Russia support | China support | Final winner |

| Angola | M P L A | U N I T A | M P L A |

| Mozambique | FRELIMO | COREMO/FRELIMO | FRELIMO |

| Rhodesia | Z A P U | Z A N U | Z A N U |

| South Africa | A N C | P A C | A N C |

| South West Africa | SWAPO | S W A N U | SWAPO |

Ultimately the Soviet Union had sponsored the ruling party that went on to rule in all countries - except in Rhodesia where they had aligned with ZAPU after the approach by Joshua Nkomo.

Sweden advised both ZANU and ZAPU, that it had decided ”not to give financial support through a fund-raising campaign to any of the two liberation movements of Zimbabwe”, adding that "we are sorry to say that we have not found it possible for one organisation, without the cooperation of the other, to work effectively... Neither have we found the cooperation terms between the two organizations in a state that we had expected them to be. We appeal to you to solve the cooperation problems that now prevent you from performing your more important aim and duty”.

ZANU’s first contingent of five men, including Emmerson Mnangagwa - who went on the replace Mugabe as President after instigating the military coup d'etat in 2017 - was sent for military training to the People's Republic of China in September 1963.

Mnangagwa was in the gang that infiltrated the country. A White forestry worker was killed by stabbing  multiple times at a road block in July 1964 near Melsetter on the eastern border. He was returning home after dropping two of his daughters off at boarding school but his wife and other daughter were rescued by a passing motorist.

multiple times at a road block in July 1964 near Melsetter on the eastern border. He was returning home after dropping two of his daughters off at boarding school but his wife and other daughter were rescued by a passing motorist.

From January to March 1965, 54 members of ZANU received training in Ghana. They infiltrated into Rhodesia in May 1965 and most were arrested over a period of time. Between March 1964 and October 1965, 76 ZAPU were trained in Moscow, Nanking and Pyongong (North Korea). At least 24 were arrested shortly after crossing the border.

These events preceded Ian Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) from the British in November 1965. Some historians state that UDI triggered the armed struggle in Rhodesia but nationalists decided to take up arms in 1962.

ZANLA infiltrated in a few groups near Chirundu in March 1996 and each had different objectives. One gang attempted to sabotage powerlines near Chinhoyi (then Sinoia) where they were engaged in a sustained contact and all were killed by the Police. Documents found on one body showed that training had been undertaken in Nanking at the end of the previous year. This date, 28th April 1966, marks the beginning of the 'Second Chimurenga' by nationalists.

The second gang that was based in the Zwimba area shot a farmer and his wife in their isolated  farmhouse after knocking on the door near the Beri River outside Gadzema in the early hours of a Monday morning a few weeks later. Two young children were unharmed by the volley of gunfire directed that was towards their crib.

farmhouse after knocking on the door near the Beri River outside Gadzema in the early hours of a Monday morning a few weeks later. Two young children were unharmed by the volley of gunfire directed that was towards their crib.

The section of two men from the 1966 incursion headed for the Fort Victoria area and another of five men had orders to sabotage the Beira-Umtali oil pipe-line and attack white farmers. All seven were arrested before accomplishing their objectives.

Another seven men headed for the Midlands area and it is possible that their purpose was to make contact with their President, Sithole, who was under restriction at Sikombela, near Gwelo.

Initially both ZAPU and ZANU were hosted by Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia that had recently been recently awarded independence as Northern Rhodesia. Each Nationalist group fought a separate war against the Rhodesian security forces, and the two groups had the odd clash with each other over time. Initially tension flared up during training and this resulted in up to 200 casualties in Zambia and Tanzania in seperate incidents.

After the military coup in Portugal in 1974, Portuguese troops hastily departed from Mozambique and FRELIMO took over government. A civil war ensued until 1992 but Robert Mugabe's ZANU movement, and its military wing ZANLA, infiltrated from bases that were established in Mozambique with protection that was provided by FRELIMO troops.

When Mugabe was questioned about ZANU/ZANLA internal disputes, he acknowledged that there was ideological infighting in 1974-5 which led to the formation of the Zimbabwe Independent People's Army (ZIPA) by young left-wing cadres in Mozambique who were frustrated by inactivity. ZIPA represented a youthful ideological challenge to the older and less well educated generation of ZANLA guerrilla commanders. Originally, ZIPA had a High Command of 18 leaders - 9 from ZANU and 9 from ZAPU. Tension flared and 50 ZIPRA were killed by ZANLA in two camps in Tanzania in August 1976. ZAPU withdrew from the combined army. Those that remained in Mozambique were incarcerated.

The People's Republic of China remained the primary external source of training and weaponry, although from 1977 ZANLA fighters were also the recipients of training in Ethiopia; and support from Romania and Yugoslavia.

Recruitment by Nationalists

The Nationalist leaders lacked foot soldiers when the campaign of violence was instigated. Academic Fay Chung joined ZANU in Lusaka and wrote that between 1965 and 1972, there was a shortage of ZANLA recruits in Zambia. Initially, only poor youths from Mumbwa - where 90,000 small holder farmers mainly of the Karanga tribe had immigrated from the southwestern part of Rhodesia into the fertile farming area in Central West Zambia - were prepared to enrol. As a result, the oldest and most experienced ZANLA were not highly educated. Many of them had only received a few years of primary education. Some were illiterate.

Both ZANU and ZAPU used forced conscription around 1973. Young Blacks from Rhodesia that had settled in Zambia were captured and forced to join up - such as conscript Josiah Tungamirai who joined ZANLA and rose through the ranks to become Political Commissar. He went on to head the Air Force and became a minister in Mugabe’s government.

ZANLA consisted of a dozen dedicated guerrillas then a number of ZIPRA joined them in the late 1960s. By 1972, ZANLA numbered a few hundred after as many had been captured or killed.

At that time, women contributed significantly because they were better suited for the long walk from the Mozambican and Zambian borders into Rhodesia carrying loads of weapons on their heads, not only because they were already accustomed to carrying heavy loads of water and firewood, but also because the RSF were less suspicious of women.

The first report of abductions of schoolchildren was in mid-1973 when ZANLA took 350 students from St Albert's Roman Catholic mission in north-eastern Rhodesia. All but 25 were returned by Rhodesian security forces.

'Zambianization' in Zambia whereby law prevented non-Zambians from owning a business, proved to be another factor that forced disadvantaged former Rhodesians in Zambia to enrol as recruits. There was a surge of recruits and Chung wrote that ZANLA numbers swelled to over 3,000 in Zambia by 1974.

ZIPRA abducted 400 African pupils (including 170 females) from the previously Swedish run Manama Lutheran Mission's secondary school with five teachers, two nurses and a clerk in January 1977. They were taken to neighbouring Botswana for training and $20,000 school fees were also stolen. Five students and two teachers managed to escape the kidnapping.

Adverse publicity after the latest forced abduction of school children to take up arms for Nationalism prompted a different approach to recruitment. Josiah Tungamirai, former conscript, explained in an interview from his time as ZANU/ZANLA Political Commissar: "... in Mashonaland Centre and part of Mashonaland East there were areas where we had fought the war and everybody had gone into the bush. The cultivation of the land had come to a standstill... In the years from 1977 to 1979, the numbers of homeless from Zimbabwe increased greatly and at the end of the day we had over 40,000 refugees in Mozambique... Because at that stage we were ... recruiting ... from the refugee camps and if the refugees had not been fed... then our source of recruitment would have dried up." The link that is revealed in that interview between Nationalist recruitment and refugees explains the reported presence of refugees in or around ZANLA training and staging camps. This wave of trainees received food, medicines and clothing from Aid that had been donated primarily from the Nordic countries.

Women were not mere porters as they were trained in combat and there are reports that some were effective adversaries in battle.

According to Tanya Lyons who interviewed former female cadres: “ZANU wanted (to raise) soldiers, so no family planning was allowed.” This was a problem for women who wanted to participate in the struggle without the burden of pregnancy, birth and mothering. To be caught with condoms resulted in imprisonment. A former female cadre said that it was acceptable to go through hardship and go without food for four days, but “sex for soap” or the luxury of sugar was an option in training camps. The party policy was for women to either remain pure or become mothers of the next generation of soldiers. The maternity camp for ZANU was Osibisa at Chimoio.

‘Rufaro’ explained that in ZIPRA: “When women were not pregnant they were just soldiers like the men, and soldiers take orders. The commanders didn’t want women to have children in the bush. They treated us like their children... The women who got pregnant were sent to Victory Camp at Lusaka.”

New Farm (formerly Adriano’s Farm) in Chimoio (formerly Villa Perry) had been abandoned  by the owner in 1975 and it was handed over to ZANU. It was transformed into multiple camps for training, the accommodation of hard-core cadres that had trained in China, Yugoslavia and Tanzania and as a launch base into Rhodesia. ZANLA commander Josiah Tongogara resided in the original homestead ‘The White House’ with others of the general staff. Takawira Camps were for general military training, engineering, anti-aircraft training and accommodation of experienced fighters. Mbuya Nehanda A was for female military training and Mbuya Nehanda B (the other name given to Osibisa) was a maternity wing for expectant and young mothers. It was notorious for bathing in icy cold water in an attempt to increase strength and determination. Chung wrote that experienced female guerrillas also stayed there in between their deployments. There was a camp for internal security/intelligence/prison, a camp for military stores/vehicles and piggery. There was a college of ideology, a general school and camp hospital.

by the owner in 1975 and it was handed over to ZANU. It was transformed into multiple camps for training, the accommodation of hard-core cadres that had trained in China, Yugoslavia and Tanzania and as a launch base into Rhodesia. ZANLA commander Josiah Tongogara resided in the original homestead ‘The White House’ with others of the general staff. Takawira Camps were for general military training, engineering, anti-aircraft training and accommodation of experienced fighters. Mbuya Nehanda A was for female military training and Mbuya Nehanda B (the other name given to Osibisa) was a maternity wing for expectant and young mothers. It was notorious for bathing in icy cold water in an attempt to increase strength and determination. Chung wrote that experienced female guerrillas also stayed there in between their deployments. There was a camp for internal security/intelligence/prison, a camp for military stores/vehicles and piggery. There was a college of ideology, a general school and camp hospital.

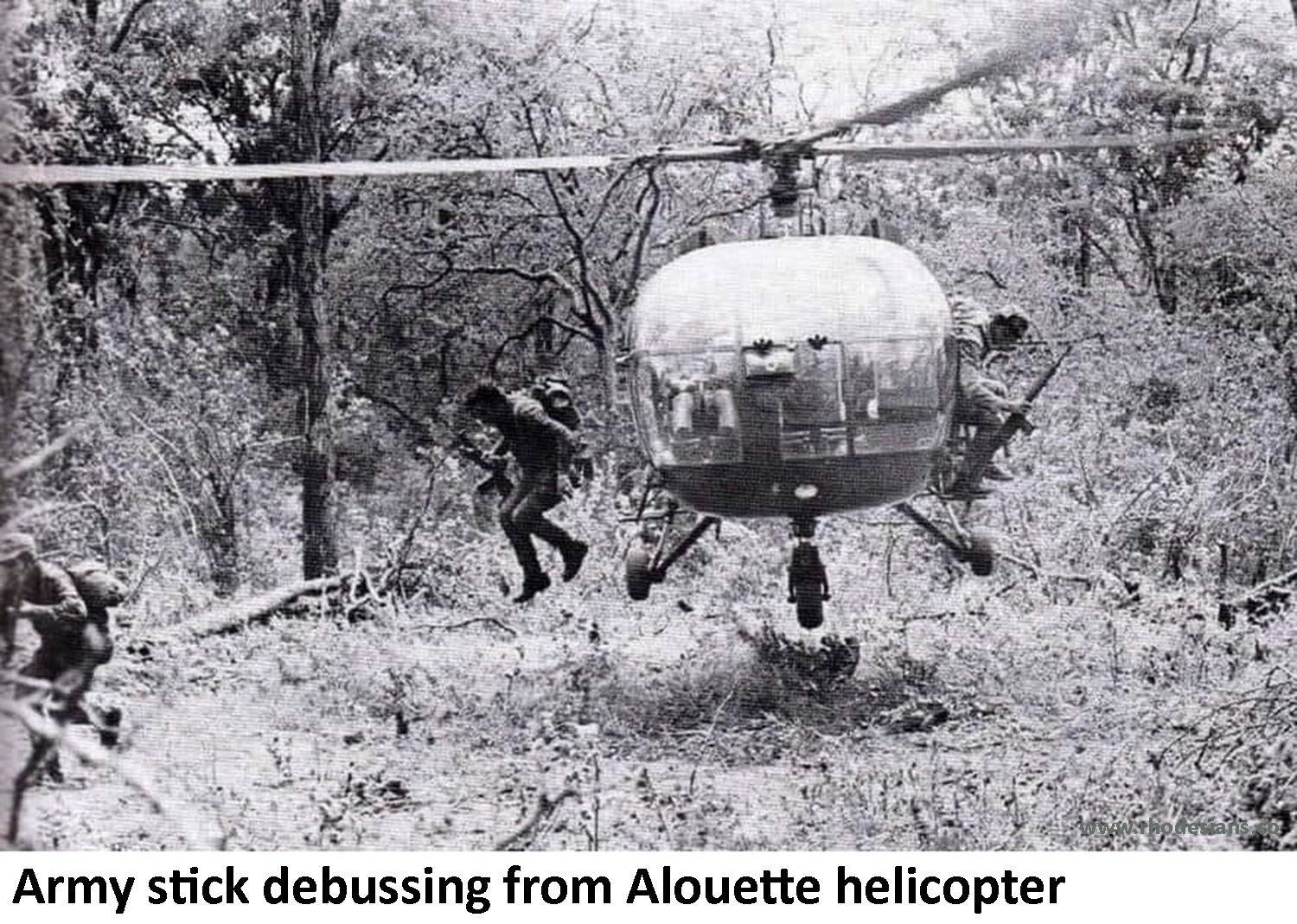

Housing 10,000 ZANLA plus political/civilian elements, Adriano’s Farm was attacked for three days from 23 November 1977 in a pre-emptive strike. 145 ground forces parachuted in and 48 were dropped by helicopters after air strikes.

In the battle they encountered unarmed cadres and seasoned veterans alike.

A KGB General was apprehended by Rhodesian ground troops and was found to speak impeccable English as though he had grown up in the United Kingdom.

One RLI machine gunner fired through a closed door at the end of a latrine when it transpired that people were hiding there. Belt after belt was fired then women and children came tumbling out when the door was shattered. The RLI gunner could not differentiate active guerrilla from someone who had been exploited by a ZANLA instructor during a moment of weakness. Camp Commander, Joice Mujuru (nom-de-guerre Teurai Ropa) who happened also to be married to Solomon Mujuru (Rex Nhongo) survived by hiding deep inside the pit latrine.

Afterwards Rhodesians claimed that more than 1,200 ZANLA were killed with uncounted women and children to the loss of one SAS trooper, one pilot and eight wounded. Peter Baxter independently wrote that 3,000 ZANLA were killed with another 5,000 wounded.

There was a predominance of members of the Karanga tribe amongst the early recruits. ZANU had become increasingly dominated by them and the process had been completed in the High Command by March 1975, when all five of the elected members were from the Karanga tribe. This included Josiah Tongorara who was the popular commander of ZANLA. During the Lancaster House negotiations he favoured a joint ZANU/ZAPU campaign in the forthcoming election. This was contrary to Mugabe's plans who told Nkomo "We have fought together but we go to the elections on our own". Tongorara was sent back to Mozambique and was killed in a motor accident when he drove into a stationary vehicle only days after the ceasefire in December 1979. Mugabe assumed his military title as the conflict was wrapping up.

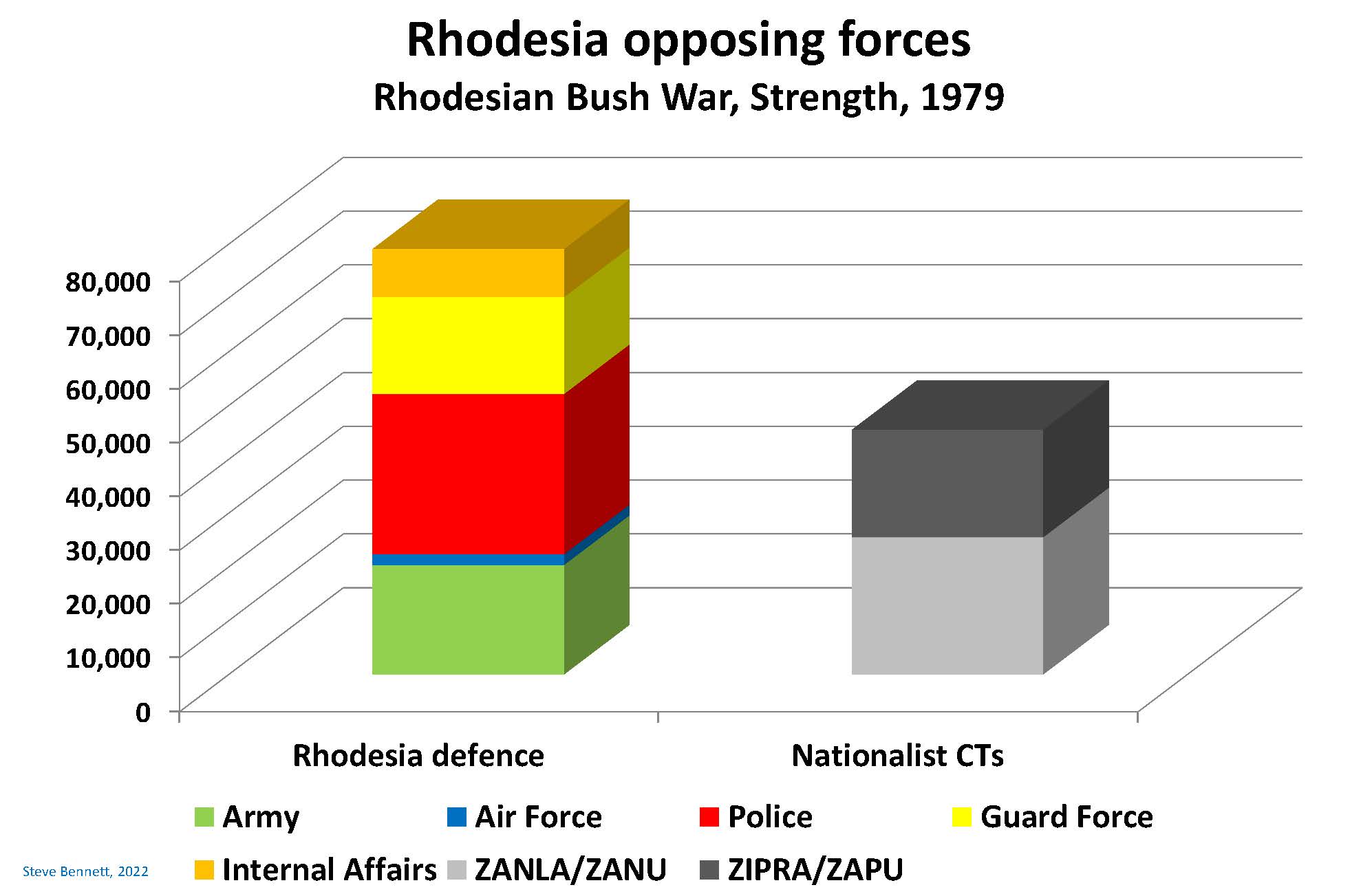

During 1979 ZIPRA had accumulated a force of 20,000 in Zambia and ZANLA had strength of 25,500 in Mozambique.

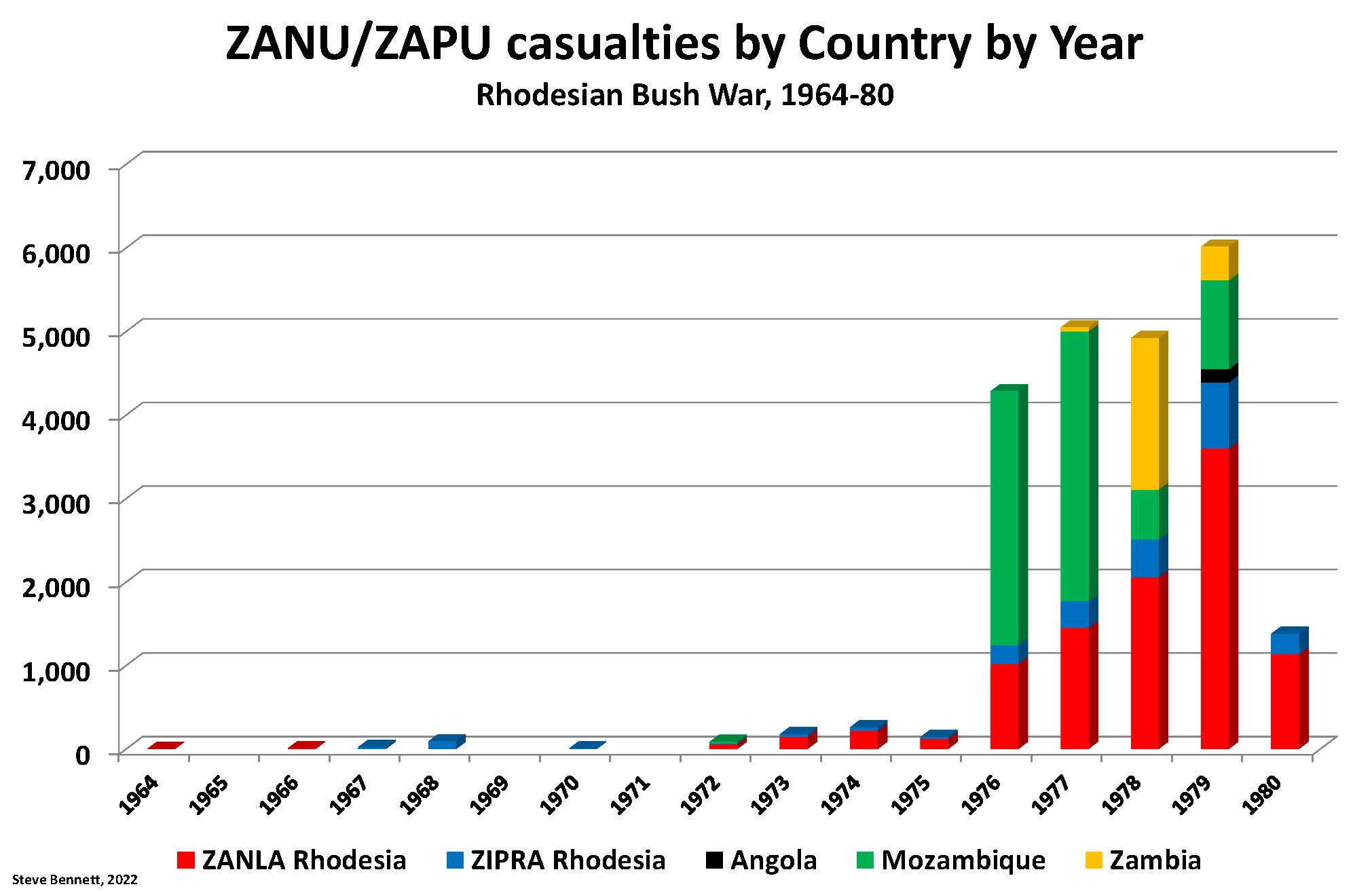

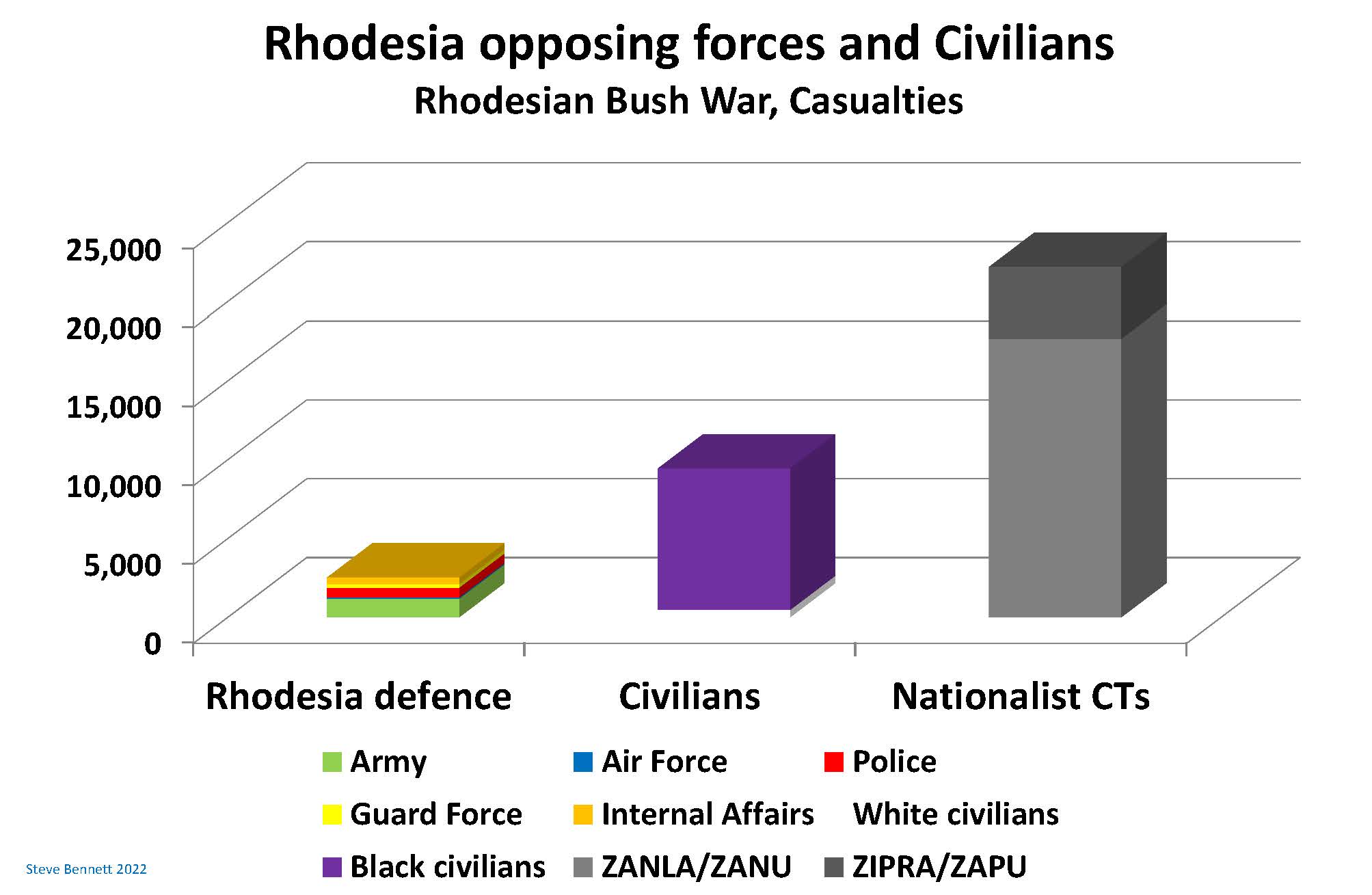

During the conflict, combined Nationalist casualties were twenty two thousand of which approximately 80% were ZANU/ZANLA.

Rhodesian defence

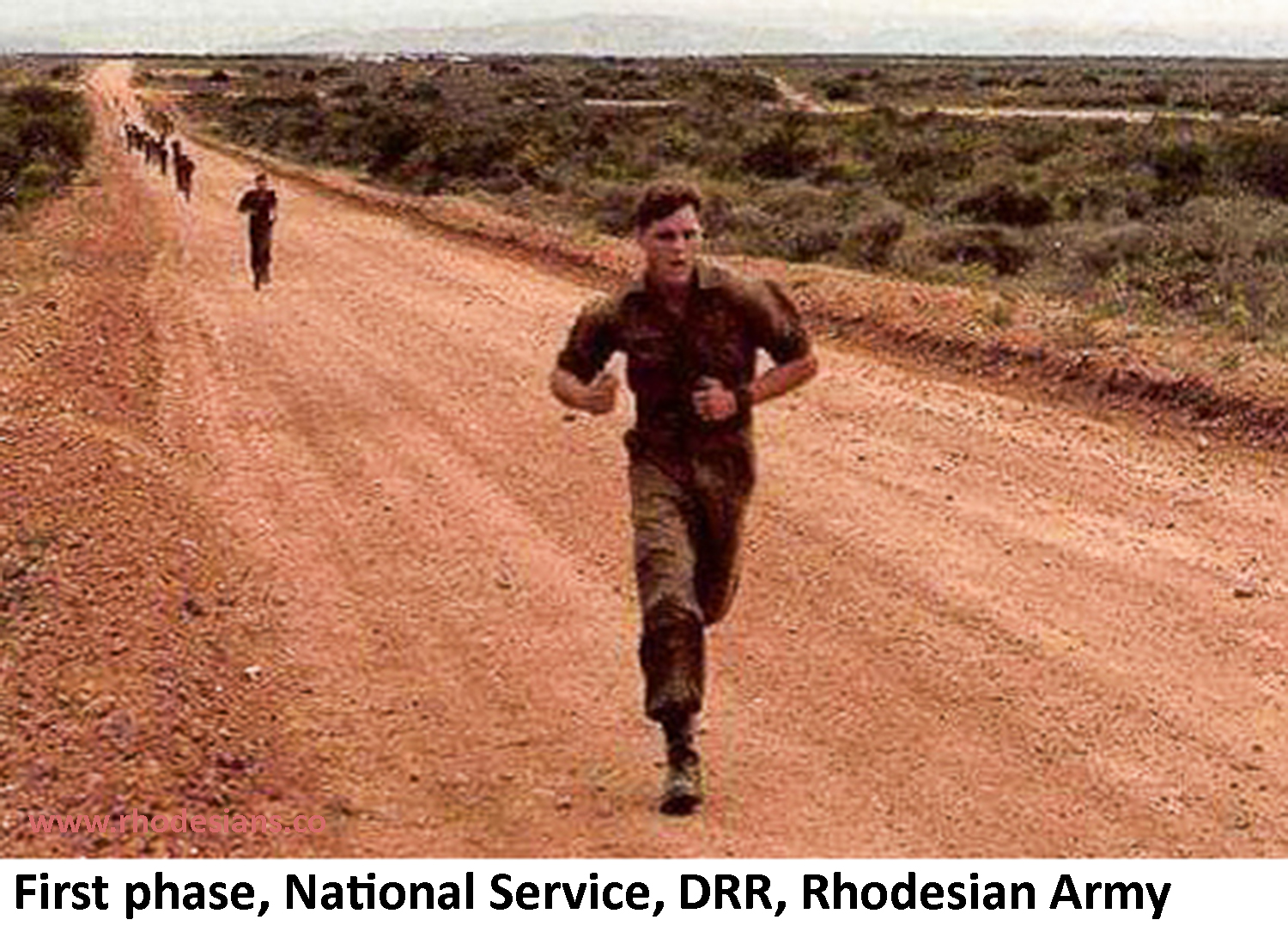

After the Second World War there had been a few occasions when requests had been made by Britain for military support from Southern Rhodesia/Rhodesia. The Federation of  Rhodesia and Nyasaland was disbanded to revert back to Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland on 31st December 1963 after only ten years. The Southern Rhodesian Army numbered 3 400 regulars and 8 400 reservists in Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR), Special Air Services (SAS), Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) and Rhodesia Regiment (RR). The Air Force numbered 1 000 and there were 100 aircraft.

Rhodesia and Nyasaland was disbanded to revert back to Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland on 31st December 1963 after only ten years. The Southern Rhodesian Army numbered 3 400 regulars and 8 400 reservists in Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR), Special Air Services (SAS), Rhodesian Light Infantry (RLI) and Rhodesia Regiment (RR). The Air Force numbered 1 000 and there were 100 aircraft.

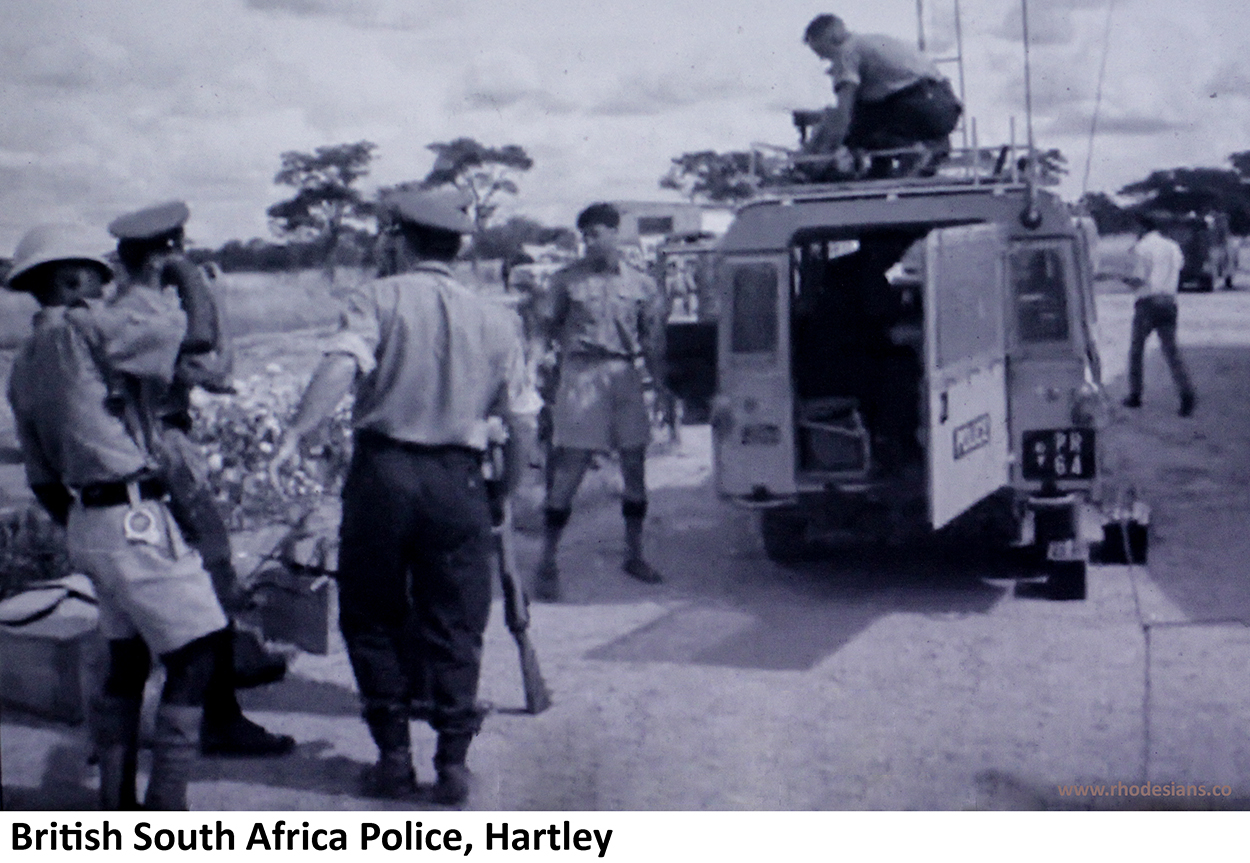

In addition, the large police force enforced law and order but BSAP officers had trained both as policemen and soldiers until 1954.

The murder of Andrew Oberholzer in July 1964 is the first fatality that resulted from violence by Nationalists. Nyasaland was granted independence by the British on 6th July 1964 and was named Malawi. Northern Rhodesia was granted independence on 24th October 1964 and was named Zambia. Southern Rhodesia had been a self-governing colony since 1923 after a referendum had been held and it was determined that it would not join the Union of South Africa. The Southern Rhodesian government announced that when Northern Rhodesia achieved independence as Zambia, the Southern Rhodesian government would officially become known as the Rhodesian Government and the colony would become known as Rhodesia. This change was never ratified by the British. Discussions with the British failed to progress to independence and concerns about a repetition of the Congo Crisis culminated in an unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) on 11th November 1965.

There had been Nationalist incursions but the first contact between ZANLA and the police in Chinoyi (formerly Sinoia) was in 1966 after a failed attempt of sabotage. The follow-up after the Viljoen murders at Gadzema a month later was commanded by the local police in  Chegutu (formerly Hartley) in the tradition that dated back to their origins. The British South Africa Company’s Police was formed by the BSAC in 1889 as a paramilitary, mounted infantry force to protect the Pioneer Column which moved into Mashonaland during the following year. After renaming to become the British South Africa Police (BSAP) in 1896 their role was mainly of law enforcement and the line between police and military was significantly blurred. However, after the police operation in Hartley, the Rhodesian Security Forces (RSF) became the government's primary instrument for conducting counter insurgency operations.

Chegutu (formerly Hartley) in the tradition that dated back to their origins. The British South Africa Company’s Police was formed by the BSAC in 1889 as a paramilitary, mounted infantry force to protect the Pioneer Column which moved into Mashonaland during the following year. After renaming to become the British South Africa Police (BSAP) in 1896 their role was mainly of law enforcement and the line between police and military was significantly blurred. However, after the police operation in Hartley, the Rhodesian Security Forces (RSF) became the government's primary instrument for conducting counter insurgency operations.

Rhodesia was declared to be a republic in 1970 so it was no longer a member of the British Commonwealth.

Initially the Nationalist incursions were successfully contained by RSF who quickly adapted to contacts in the rural areas. South Africa provided support and personnel serving with South Africa Police are reported in casualty rolls between 1968 and 1975.

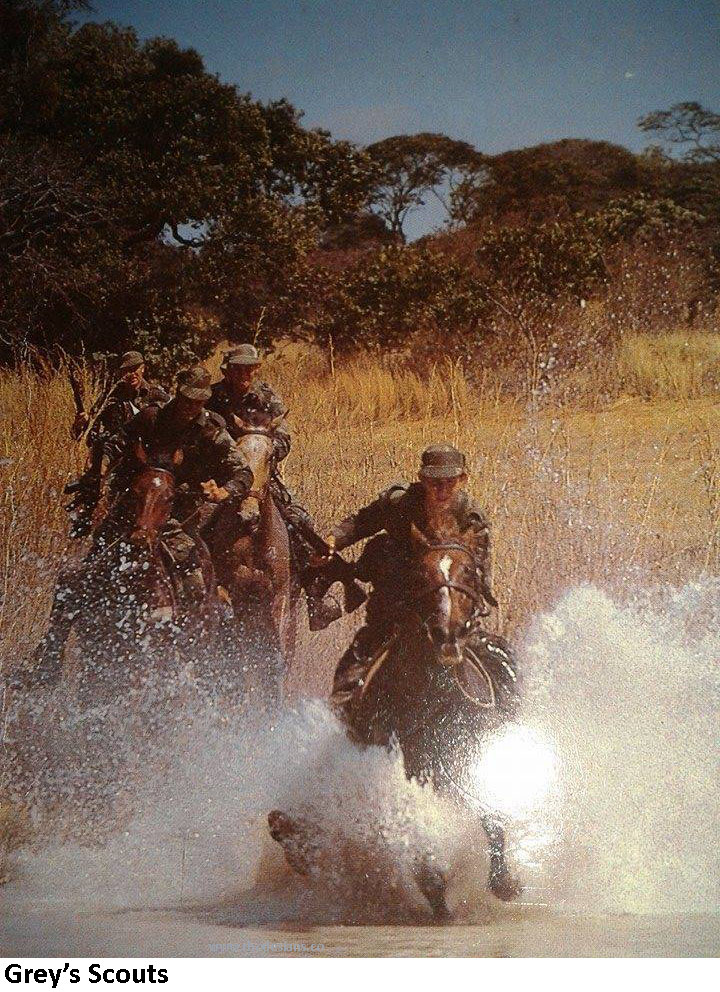

Two of the founding units, the RLI and SAS, were both specialized White units and the RAR comprised Black soldiers that were led by White officers. All other units were of mixed race. The Selous Scouts operated under the guise of being trackers but their role was primarily ‘pseudo’. A number of their force was captured insurgents that changed sides and most proved themselves to be loyal when defending Rhodesia. Selous Scouts were mainly Black and some specialized police units were predominantly Black – such as the Support Unit and Ground Coverage.

Operationally, Special Forces (RLI, SAS, Selous Scouts and Grey’s Scouts) relied on the core of regulars and they were engaged on pre-emptive external strikes at the source of incursions from Mozambique and Zambia. The RLI and RAR were deployed by parachute or helicopters into domestic Fire Force contacts.

Domestic forces were boosted with increases in the length of National Service and the Territorial reservists were called up more frequently when the number of insurgents increased. Whites had been required to report for National Service since Intake 1 for four and a half months in 1955 as soon as education had been completed. This was increased to nine months in 1966 and to a year in 1973. National Service was extended to include Black conscripts from 1978 and the Independent Companies absorbed the mixed race reserves.

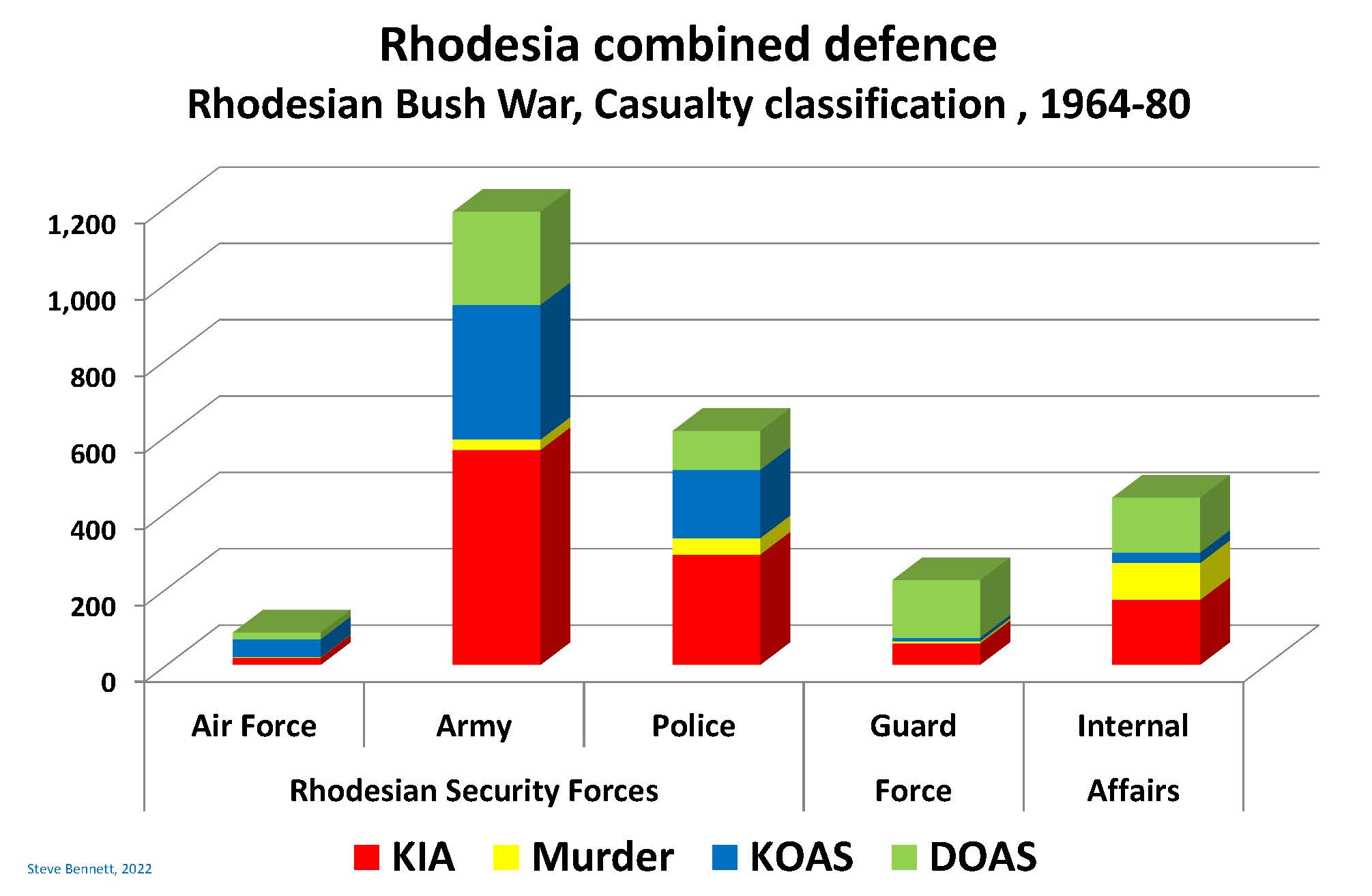

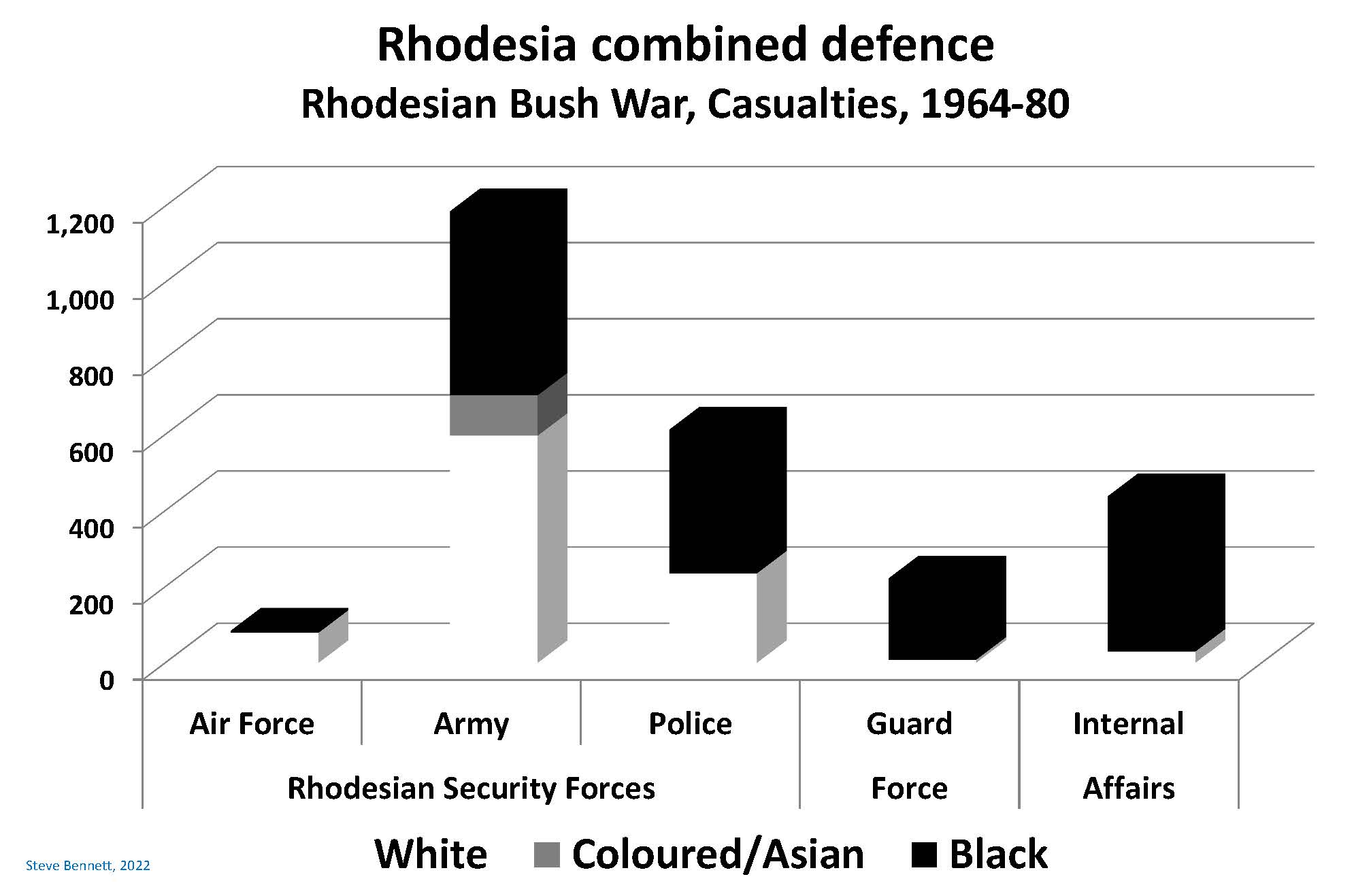

Casualties of Rhodesian defence forces between 1964 and April 1980 were 2,500. 1,900 of these were from Rhodesian Security Forces.

Rhodesian defence strength and casualties of opposing forces

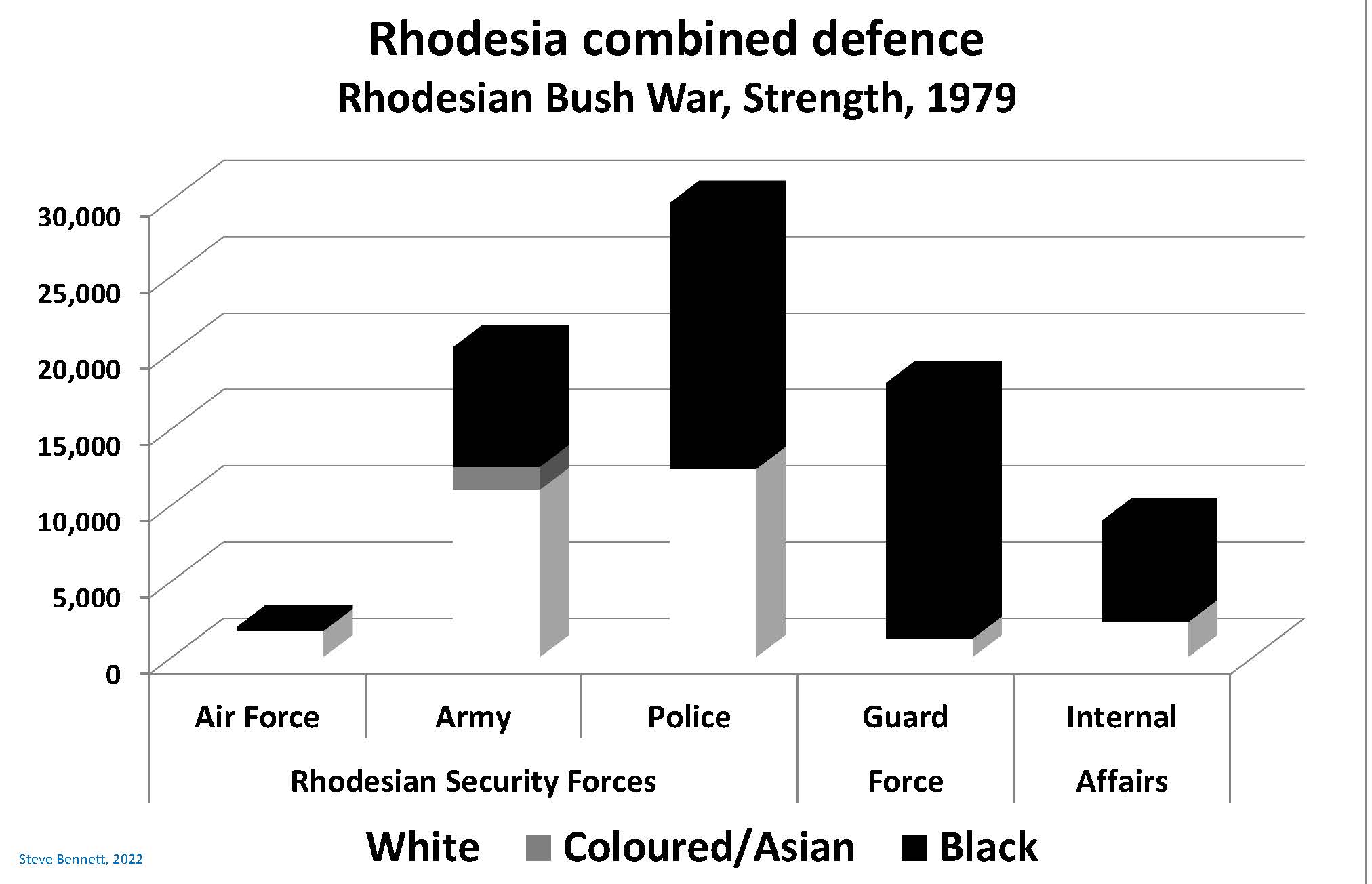

By 1974 the police had contributed 16 companies to counter-insurgency effort. In 1979 they were the largest force with 57% of RSF strength while the Army only made up 39%. The small but effective Air Force despite antiquated aircraft had fewer than 150 pilots.

The Rhodesian defence strength was 79,000 but many of these were reservists so the equivalent number on a fulltime basis was 56,000. The only occasion that there was a full mobilisation was for the election that Bishop Muzorewa won in 1979 when a total of 60,000 were deployed. Despite opposition from ZANU and ZAPU who did not compete, there was no violence, intimidation nor disruption because of the blanket of security.

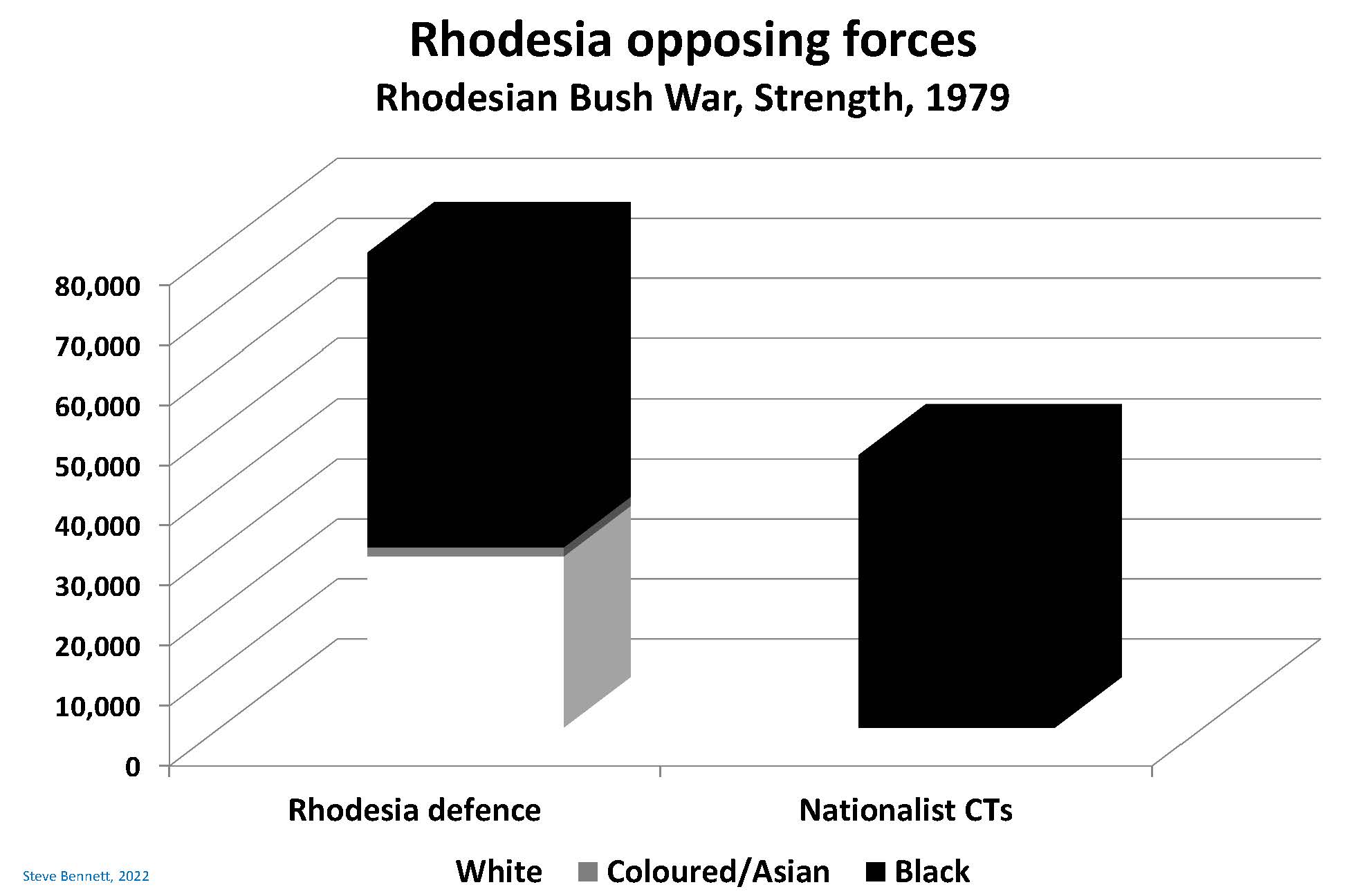

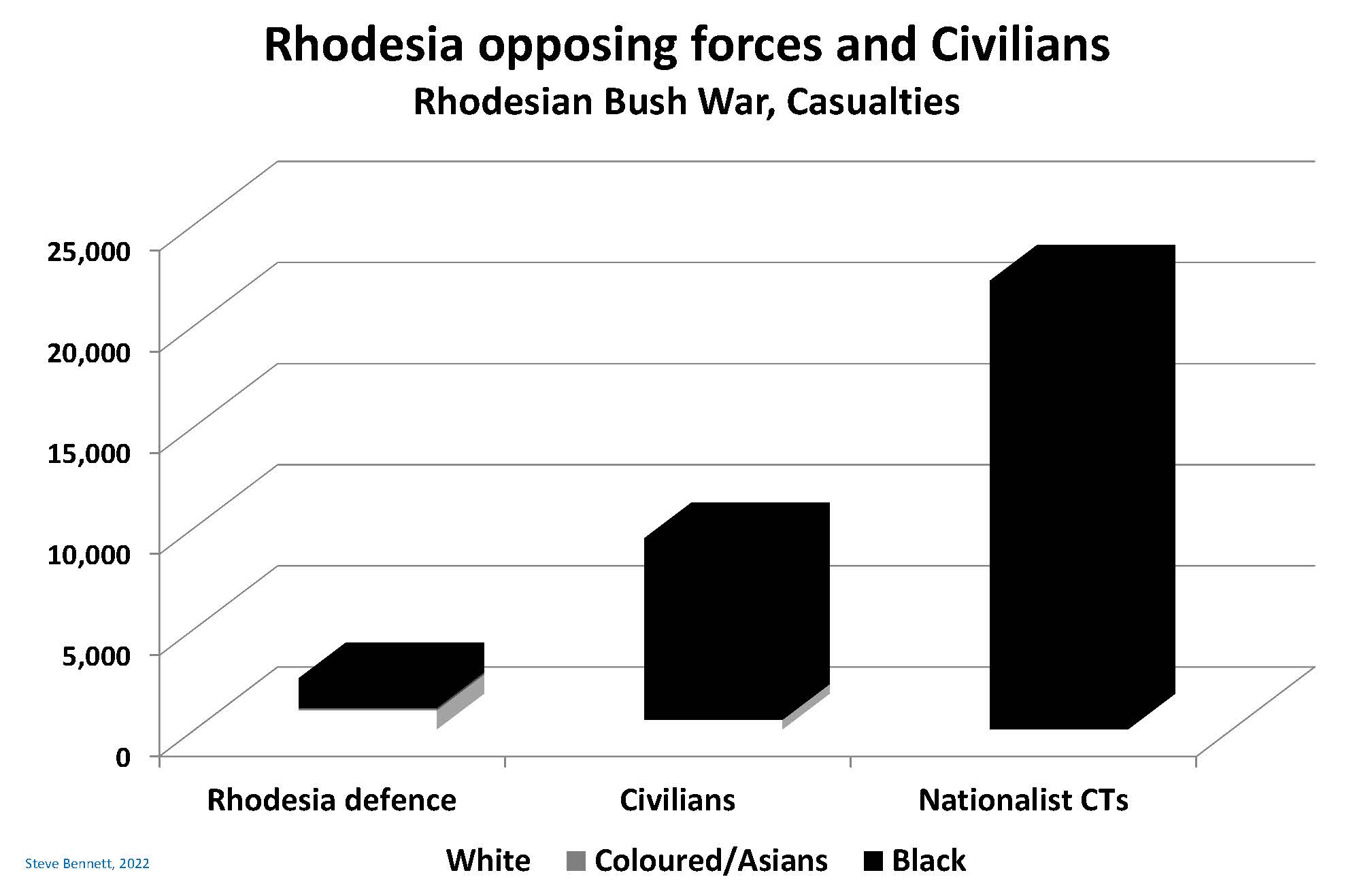

Despite public perceptions, this was not a White versus Black conflict. 49% of RSF across the police, air force and army were Black. Whites comprised 48%. Coloured and Asians reservists were mainly consolidated in the Rhodesia Defence Regiment but their contribution was less than 3% of the total RSF.

The tradition of natives bearing arms for Rhodesia that had commenced in 1916 with the  formation of Rhodesian Native Regiment has continued. Guard Force and The Ministry of Internal Affairs provided defence to the Black communities. Their contribution is recognised from casualties of one quarter of total Rhodesian defence casualties from one third of total defence strength. Guard Force were known for their role with the 200 Protected Villages but their role in providing protection for commercial farmers and for rail transport was not so widely acknowledged. The Black contingent involved in the defence of Rhodesians and infrastructure was 62% of the total. Europeans made up 38% and Coloured/Asians the remaining 2%.

formation of Rhodesian Native Regiment has continued. Guard Force and The Ministry of Internal Affairs provided defence to the Black communities. Their contribution is recognised from casualties of one quarter of total Rhodesian defence casualties from one third of total defence strength. Guard Force were known for their role with the 200 Protected Villages but their role in providing protection for commercial farmers and for rail transport was not so widely acknowledged. The Black contingent involved in the defence of Rhodesians and infrastructure was 62% of the total. Europeans made up 38% and Coloured/Asians the remaining 2%.

White personnel made up 48% of RSF strength, and they also accounted for 48% of the casualties. Coloured/Asians comprised 2.9% of RSF strength and 5.6% of the casualties.

Whites comprised 38% of the forces involved with Defence and 37% of all Casualties.

The following criteria were applied to the classification of casualties for the charts:

'KIA' is the total from enemy action - from gunshot, mortars and rockets in ambushes and contacts; and land mines.

'KOAS' is the total from accidents - vehicular, accidental gunshot discharges and laying of land mines, "friendly fire" and mistaken identity etc.

'DOAS' are deaths on service from natural causes, illness, self-inflicted etc.

'Murder' is individuals or pairs that were apprehended and murdered by Nationalist CTs on home leave/beer halls or travel. It is also used in the case of Selous Scouts when "turned" Nationalist CTs shot sleeping members of their patrol when they were on guard duty.

In general, hostile action was incurred in almost half of all casualties. When 'Murder' is added to 'KIA' they reach 50%. Accidents almost took a third with 30% in 'KOAS'. Two thirds of these were in the operational area. 20% were 'DOAS' which is mainly from illness and within this group 40% were from natural causes and cancers.

Rhodesian defence force casualties numbered 2,500. Nationalist CT casualties were twenty two thousand bringing a ratio of 9:1. They are illustrated by unit and by race in the following charts.

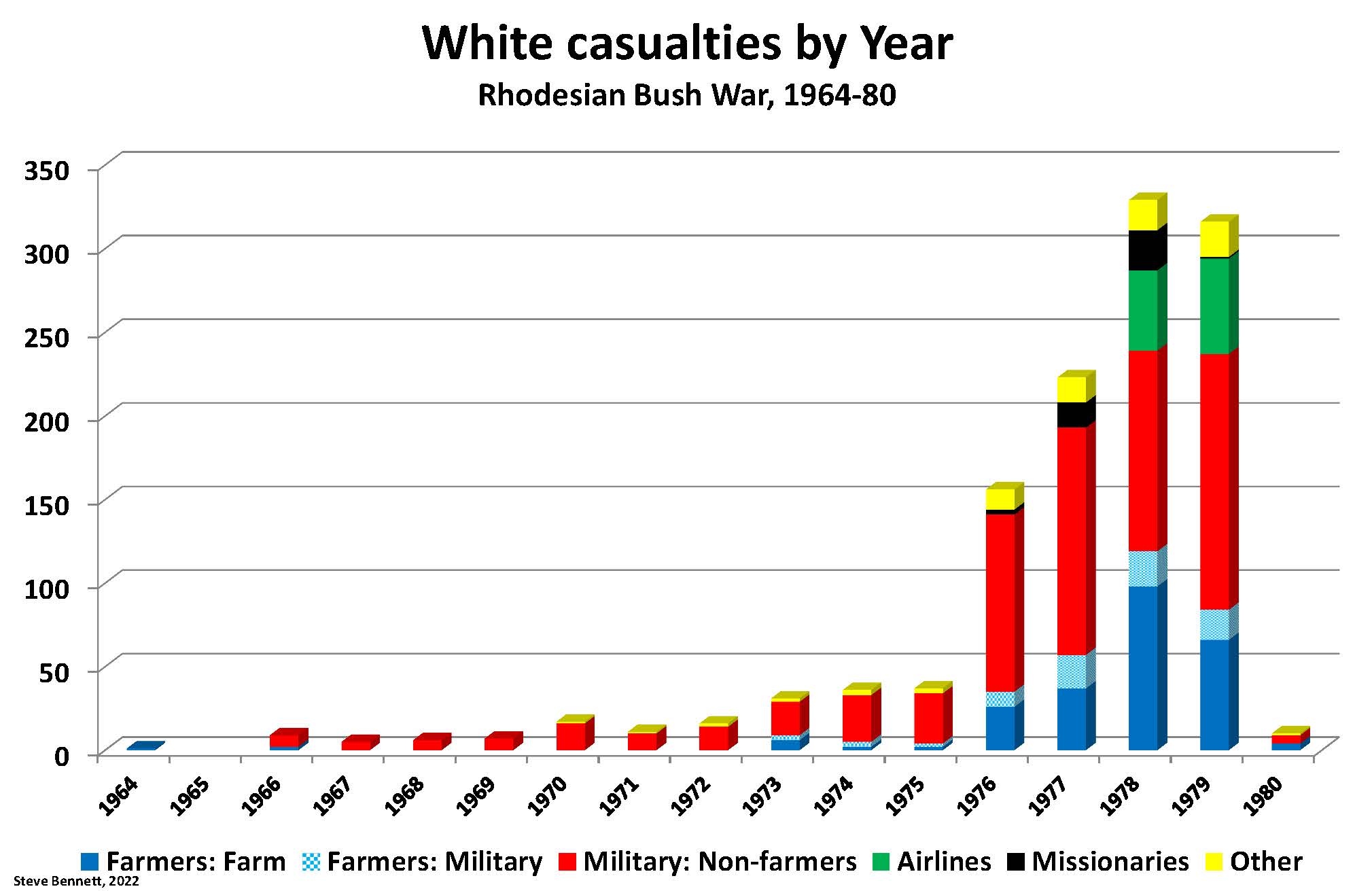

Almost 500 White civilians were killed. Half of these were farmers and more than 100 civilian White passengers perished when two passenger aircraft were struck by SAM-7 missiles fired by ZIPRA. The few survivors from one crash landing were massacred at the site. White casualties included a few dozen missionaries that were murdered in remote locations where they were ironically serving rural communities.

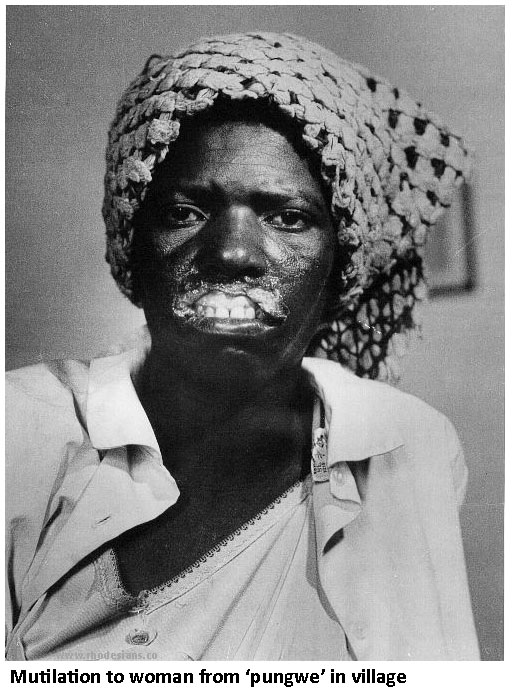

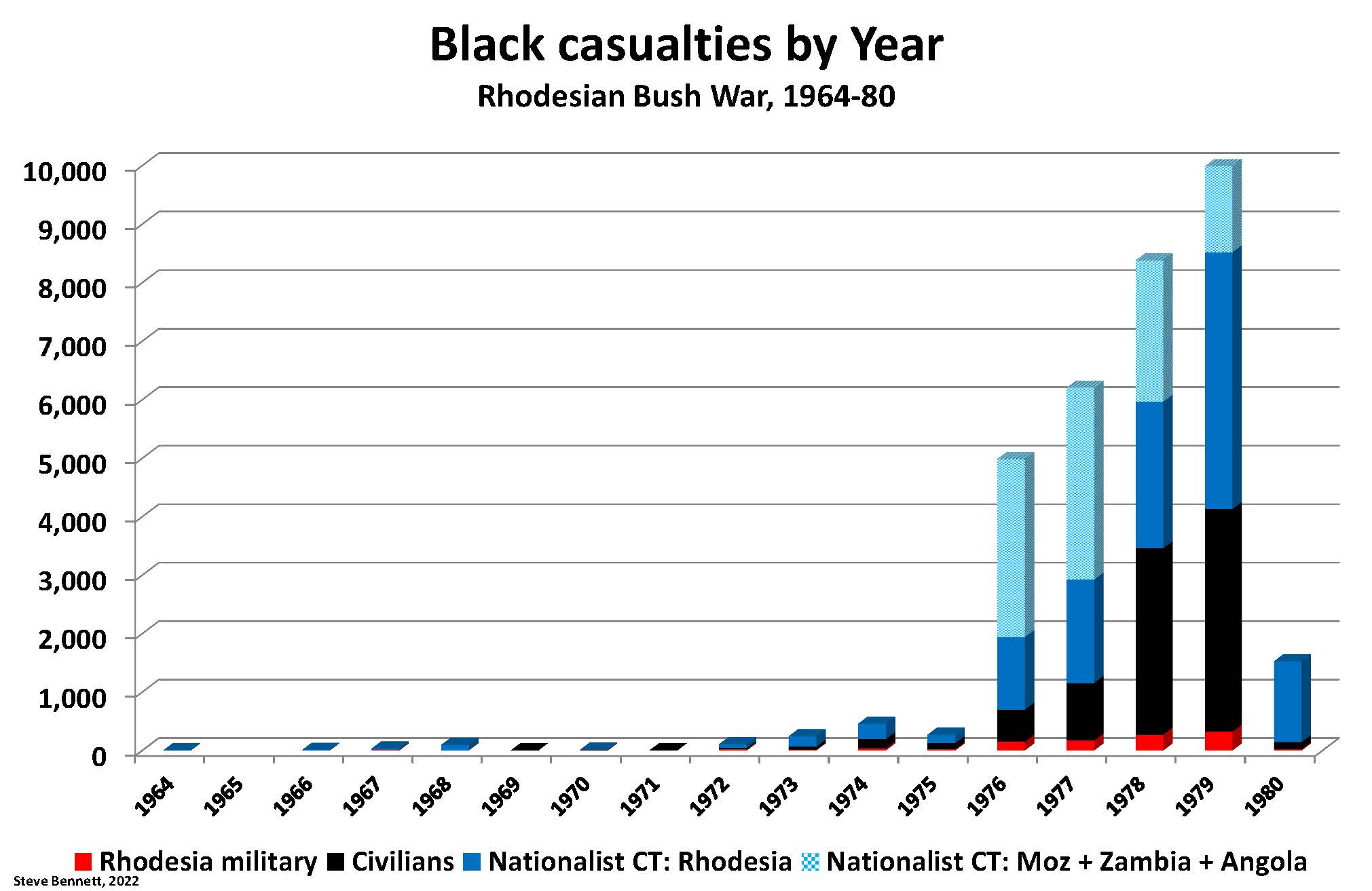

There was an unexpectedly high casualty count of Black Civilians. According to the Government, 7,000 civilians had died over eight years. 3,750 of the black victims were killed by guerrillas, mostly as ‘sell-outs’ - a term the guerrillas use for anyone from teachers or village headmen to those who resisted demands for food, shelter or information about the movement of Government troops. Many targeted victims, like the woman in the photo below, were mutilated. Family members were forced to eat flesh from lips or ears. Seeing the ghastly mutilations in the community were stark reminders about the message from the 'pungwe' (the overnight assembly of insurgents with villagers where liberation war songs that denounced the government were taught. During these, examples were made of those that were deemed to be disloyal through murder or brutal disfigurement). In addition to the sell-outs, some 2,800 others have been listed as killed by Government forces, either as a result of “crossfire” or for breaking curfew, or because, in the words of communiques, they were “running with and actively assisting terrorists.”

Mugabe applied the philosophy of Mao Zedung to ZANLA and the importance of a good

relationship between themselves and the rural population. Researchers Ngwenya and Malopo in 2018 compared the district of Zaka that had been infiltrated by ZANLA with Bulilima district in Matabeleland that had been under ZIPRA.

relationship between themselves and the rural population. Researchers Ngwenya and Malopo in 2018 compared the district of Zaka that had been infiltrated by ZANLA with Bulilima district in Matabeleland that had been under ZIPRA.

ZANLA maintained contact with the masses and their mode of politicising them was through 'pungwes'. Given that the youth and villagers spent sleepless nights under political indoctrination, it goes without saying that they found it hard to cope with their daily chores. The irony is that the same guerrillas who subjected peasants to pungwes needed food and other services from the same peasants daily. “We usually finished singing around 5–6 in the morning. Thereafter, we were expected to cook, wash and do other guerrilla errands such as patrolling communities and moving war materials like landmines from one community to another” elaborated one villager. The Soviet Union Lenin’s perspective on the guerrilla war was that guerrillas should concentrate on fighting the enemy forces as partisans. Accordingly, in ZIPRA operated areas, there were no pungwes. “ZIPRA guerrillas kept to themselves, away from the villagers” said one Matabele as they experienced little or no interference from ZIPRA.

The endless interaction between ZANLA and the Shona villagers during indoctrination increased their risk as villagers were invariably caught in cross-fire when security forces opened fire on sighted insurgents.

Black civilian casualties are estimated to total 9,000 from 1964 through to Independence in 1980. With a higher proportion of ZANLA within Rhodesia for most of the time, and the proximity that they had with the population, it is possible that a higher ratio of Shona speaking civilians would be within the number of Black casualties that were caught up in “cross-fire” during operations or as “sell-outs” by insurgents. The coercion from the pungwes may have endured within those rural communities for beyond the first election which ZANU won very convincingly and still are. Opposition political parties come and go but ZANU-PF has won every election since 1980.

Nationalist casualties within Rhodesia numbered 12,000 and they are considered to have exceeded 10,000 from pre-emptive raids in Angola, Mozambique and Zambia. Estimates in the literature of external casualties vary considerably and this is due to the very low counts that were released by the government. Conservative counts only reach 6,000 for ZANLA plus ZIPRA in Angola, Zambia and Mozambique. The few raids into Botswana were largely successful abductions so casualties were low. A review of documented operations that were undertaken with estimates of casualties of potential threats to Rhodesian security slightly exceeded 10,000. The numbers of 'refugees' were not included despite Tungamirai stating that 60,000 refugees had been designated to become recruits so it is likely that many were outside the specific target zones during re-emptive strikes so could have been inadvertenly eliminated. They were clothed and fed by NORDIC donations that had been provided to ZANLA.

Nkomo held most of his ZIPRA forces back in Zambia for a conventional assault so they suffered fewer casualties within Rhodesia. The disparity between ZANLA and ZIPRA numbers in the field is demonstrated during the peak mid-summer incursions of 1978-9. 16,533 ZANLA entered whilst ZIPRA despatched 3,602 in those two months.

80% of the twenty two thousand Nationalist CT casualties were expected to be ZANLA. The ratio was roughly similar both internally and externally.

In round numbers, the casualties that combine to bring up 34,000 are:

22,000 Nationalist CTs

9,000 Black Civilians

2,500 Rhodesian defence forces (1,900 Rhodesian Security Forces)

500 White Civilians.

Total White casualties slightly exceed 1,500. Each category is charted by year from 1964 through to 1980. The escalation from 1976 is illustrated by an increase from Farmer and Defence force casualties. Farmers that are killed on their own farms are shown in dark blue and farmers that are casualties while on military call-up are shown in light blue. Defence casualties from non-farmer personnel are red bars. Civilian airline victims are green bars. Combined missionary/nurses and Red Cross casualties are in black bars.

Black casualties have been charted below. Rhodesian defence casualties are comparatively light (red bar) when compared with civilians (black) and Nationalist CT losses (blue). Nationalist CTs within Rhodesia are dark blue and the external pre-emptive strikes in Angola, Mozambique and Zambia have been combined into light blue bars.

The ratio of casualties as a proportion of the population is quite similar for both Blacks and Whites. The highest White casualty count occurred in 1978. They were 0.13% of the estimated White population at that time. Black casualties were at their highest in 1979. This is 0.14% of the total Black population at that time.

Epitaph

The Rhodesian Bush War had taken 34,000 lives over 16 years.

Tragically another 21,000 lives were lost over the next seven years from 1980. It was in 1987 that Prime Minister Robert Mugabe had subjugated the Matabele tribe, replaced the Lancaster House constitution and appointed himself to the role of President.

He remained in power until he was deposed in the military coup d’état in 2017. The trigger point came when he was attempting to elevate his wife to be second-in-command.

References

Alexander, J, 2020. Transnational Military Training in Boma, Eastern Angola. University of Oxford, Military memoir and culture, Studies in Society and History, 62, 3 (2020), 619-50

Amnesty International, 1978. Annual report.

Anonymous, 2022. Former special forces.

Chung, Fay, GlobalSecurity.org. Rhodesian Bush War - Second Chimurenga, Zimbabwe Liberation Struggle.

Cilliers, J K, 1985. Counter insurgency in Rhodesia.

Cocks, C, 1998. Fireforce.

Cole, Barbara. The Elite: The Story of the Rhodesian Special Air Service

Friedman, Herbert A. Rhodesian Psychological Operations 1965-80.

Gondola, 2002. The history of Congo.

Henkin, Yagil, 2013. Stoning the Dogs: Guerilla Mobilization and Violence in Rhodesia. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism Volume 36 (6):503-532.

Lyons, T, 1999. Guns and guerrilla girls. Women in Zimbabwe National Liberation struggle. Thesis. University of South Australia, Adelaide.

Musarurwa, W D. African Nationalism in Rhodesia. Web version of Who’s who by Richard Cary and Diana Mitchell.

Ngwenya, C and Molapo, R R, 2018. The politics and history of the armed struggle in Zimbabwe: The case of ZANU in Zaka and ZAPU in the Bulilima District. Journal for Contemporary History 2018 43(1):70-90

Onslow, Sue. Robert Mugabe and Todor Zhivkov. Wilson Center, Insight and Analaysis. New World Encyclopaedia/Rhodesian Bush War.

Onslow, Sue, 2009. The impact of anti-communism on white Rhodesian political culture, Donal Lowry in Cold War in Southern Africa: White Power, Black Liberation. Routledge.

Onslow, Sue, 2013. Southern Africa in the Cold War, Post-1974. Wilson Center, History and Public Policy Program, Critical Oral History Conference Series

Pritchard, Joshua, 2018. Race, identity, and belonging in early Zimbabwean Nationalism(s), 1957-1965. Robinson College, Cambridge.

Smith, Peter, 2006. Global warming. The fire of Pentocast in World Evangelism. An anecdotal history of Elim Missions (1919-1989).

The Nordic Africa Institute/Liberation Africa/Interviews/Josiah Tungamirai, 1996. ZANU/ZANLA former Political Commissar Air Marshal.

Thornycraft, Peta and James Rothwell, 2017. Callaghan government accused of ignoring evidence Mugabe behind 1978 slaughter of British missionaries. Johannesburg, 20 May 2017, 7:03pm. The Telegraph.

Tompkins, Paul J. Jr. United States Army Special Operations Command/Unconventional Warfare Case Study: The Rhodesian Insurgency and the role of External Support: 1961-1979.

Walls, Peter, 1980. Letter to Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister. Social media.