Tribal history of Malawi (formerly Nyasaland) and the role of David Livingstone then Harry Johnston to end the slave trade

Early history and overview of Nyasaland

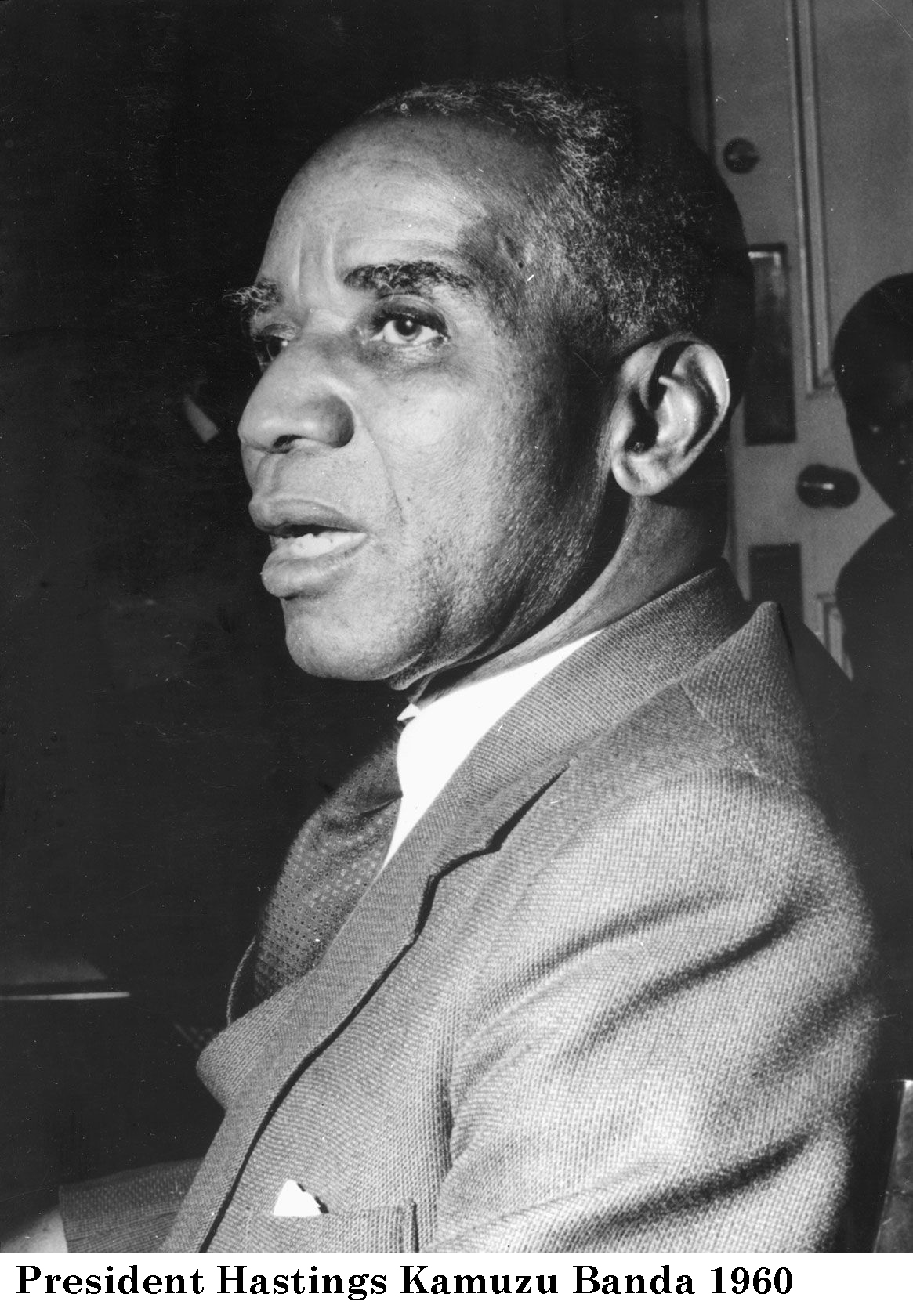

In the literature, the name 'Nyasaland' is used extensively even though the country was  officially called the 'British Central Africa Protectorate' until July 1907. It became Independent from Britain and was renamed 'Malawi' on 6th July 1964; one year after the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was dissolved.

officially called the 'British Central Africa Protectorate' until July 1907. It became Independent from Britain and was renamed 'Malawi' on 6th July 1964; one year after the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was dissolved.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries the Ngonde Kyungu rulers were able to consolidate and extend their power over the indigenous clans that they had conquered, partly by giving them a greater measure of administrative authority in the more centralized kingdom. The kingdom became more integrated, the legitimacy of the Kyungus was strengthened and tribute flowed to the capital at Mbande in inland Tanganyika. The regional prestige of the polity was demonstrated in the early 1840s when Ngonde princes were able to assembly a coalition of regional polities to curb the expansion of the Bemba from the west. However, the economic prosperity of the kingdom led to the decline of royal power after the death of the able Kyungu Mwangonde in about 1839 as the Royal Council reasserted itself by electing weak men to the throne, while the regional princes, supported by the powerful cattle owning class, resisted the Council by withholding tribute and usurping control over trade.

The political fragmentation in the course of the 18th century of the once powerful Maravi chiefdoms (that originated in modern-day Republic of Congo) created a power vacuum that was exploited by new migrants who established new polities in the region. The first of these new comers were the Swahili who followed the trading routes across Lake Nyasa pioneered by ivory hunter and traders such as the lowoka, whom they displaced as middle-men in the expanding ivory trade with the coast. The political power of the Swahili traders was based on their access to firearms and the recruitment of mercenaries who enabled them to establish indirect rule over the commercial territories they staked out for themselves. Of particular importance was the trading post founded near Nkhotakota in central Nyasaland on the shores of Lake Nyasa among the Chewa descendants of the Maravi in about 1840 by Salim bin Abdullah that, through wealth accumulation and diplomacy. He transformed into the Sultanate of Marimba known as Jumbe and dominated the local chiefdoms and became a centre for the diffusion of Islam until 1895.

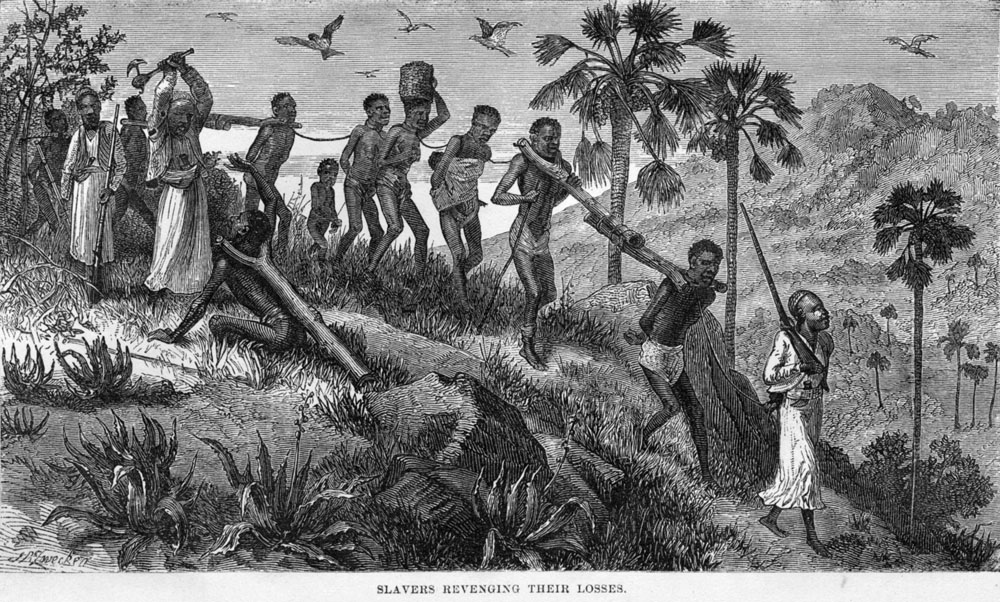

As the 19th century progressed the trade in slaves became an increasingly important  aspect of Swahili trade with the coast, with disastrous consequences for the communities subjected to slave raids, and it led to the transformation of relations of wealth and power within and between the various states and communities. The Swahili ignored the authorities and traded directly with their subjects, undermining their power in many regions, and kidnappings of fellow villagers and raids on neighbours to supply slaves to the traders for self-enrichment became. The decline in the authority of a chief because of the slave trade with the Swahili led to anarchy, chaos, fear, increased charges of sorcery, and increased alienation from the chief, who no longer was able or willing to perform services. On the other hand some polities, such as that on Mkanda, flourished as the result of large scale raiding and trading activities.

aspect of Swahili trade with the coast, with disastrous consequences for the communities subjected to slave raids, and it led to the transformation of relations of wealth and power within and between the various states and communities. The Swahili ignored the authorities and traded directly with their subjects, undermining their power in many regions, and kidnappings of fellow villagers and raids on neighbours to supply slaves to the traders for self-enrichment became. The decline in the authority of a chief because of the slave trade with the Swahili led to anarchy, chaos, fear, increased charges of sorcery, and increased alienation from the chief, who no longer was able or willing to perform services. On the other hand some polities, such as that on Mkanda, flourished as the result of large scale raiding and trading activities.

Matters were further complicated when in 1835 the Ngoni, made up of a core of Ndwande refugees fleeing the expanding Zulu kingdom in south eastern South Africa, crossed the Zambezi River and, using their superior military technology and organization, engaged in widespread raids on their neighbours such as the Chewa of southern Nyasaland. Succession disputes after the death of their leader Zwangendaba in 1848 led to their fragmentation into several small chiefdoms scattered across modern-day Malawi, Zambia and Tanzania. They incorporated the conquered peoples into their structures and engaged in raids on their neighbours for cattle and for people to assimilate into their militaristic societies. The Ngonde kingdoms alone were strong enough to defeat and repel the Ngoni in early 1840s, and they remained a constant threat. In the centre and south, between 1860 and 1885, almost all Chewa chiefs were defeated by the Ngoni and forced to flee to Mwase, Kasungu and Nkhotakota to inaccessible refuge places on mountains or in swamps. Other Chewa chiefs joined the Ngoni. The Chewa in central Nyasaland in particular were subjugated by them, but all parts of the country were subjected to their invasions and raids.

The activities of the Swahili and the Ngoni were mutually exclusive and brought them into conflict with one another as they struggled for control over people and territory, resulting in the Ngoni suppressing trade within the areas they controlled and the Swahili fermenting and supporting rebellion amongst Ngoni subjects through the supply of guns by trade. Over the long run, however, the Ngoni proved too few in numbers and to alien in culture for them to be able to impose their culture on their subjects, and as they settled down from raiding and adopted agriculture they increasingly adopted the language and culture of their subjects.

The weakness of the Chewa, as a result of the progressive disintegration of the ancestral Maravi nation, saw the infiltration of their territories by the Yao from their Rovuma homeland in Mozambique. Middlemen in the ivory trade between the Maravis and the Swahili settlements on the Indian Ocean coast in the 18th century, they settled in small groups in the highlands of southern Nyasaland from about the 1830s onwards amongst the Chewa, to whom they were culturally related, pushed by Lolo/Makua raids from the south. In the early 1860s Yao began to move into the highlands in large numbers, driven to raiding their Chewa neighbours by a severe famine and attracted by Chewa political and military weakness, where they resumed their trade in ivory and, increasingly also, slaves. The monopolisation of the ivory trade by Yao chiefs in the 18th century, and that of slaves in the 19th, led to the centralization of wealth and military power in their hands that facilitated the conquest of the Chewa.

The rise of the trader-chiefs, and the insecurity in the countryside as a result of slave raids, stimulated the development of towns around their seats of activity. These in turn, under the influence of the settlements on the coast, facilitated the adoption of Swahili culture (such as dress), technology (such as dhow building) and literacy amongst the Yao. The cultural similarities between the Yao and their Chewa subjects enabled their mutual assimilation to one another, especially the adoption of the Yao language by many Chewa and the co-option of Chewa chiefs into Yao political structures. The slow spread of Islam amongst the Yao, through the influence of Swahili scribes and traders at the courts of Yao chiefs, proceeded from the top with the conversion of the chiefs themselves in the 1870s and 1880s.

On leaving the Shirè Valley for the coast in 1861 David Livingstone left behind a small group that he had recruited from Barotseland the previous year that elected to settle in the area. Armed with firearms and a knowledge of military tactics and strategy, and with the support of the local chief on whose land they settled, the small group of interlopers raided their neighbours and passing slave caravans and, combining ruthlessness against their opponents with giving shelter to the weak, they took advantages of the prevailing drought and the disarray caused by the Yao incursions to establish mastery over the middle parts of the valley. Access to guns also provided the means to hunt ivory for trade by which they could buy more ordinance and other goods. By the middle of the 1860s they had eliminated their opponents and established the Kololo polity that was to endure until the establishment of British rule in 1891. Chewa resistance to these invasions from all sides was rallied by the Mwase Kasungu chiefdom which established control over key trade routes and warded off Ngoni raids through diplomatic initiatives with the Swahili and the Portuguese. The chiefdom provided refuge for those of the south and a focal point for the retention of cultural and religious forms elsewhere, particularly the nyau secret societies, which enabled the maintenance of Chewa identity in the 19th century and beyond.

Despite Livingstone's perceived lack of success as a missionary, his books inspired High Church Anglicans to form the Universities' Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) that eventually, after an abortive attempt at Magomero in 1861, founded a mission station amongst the Nyanja on the eastern shore of Lake Malawi in 1885. They were joined by the Free Church of Scotland's mission established at Cape Maclear on southern Lake Malawi in 1875 but the mission was moved to Bandawe in the north in 1882 and finally relocated inland to Livingstonia in 1894. In 1875 the established Church of Scotland founded a mission of its own at Blantyre. A Dutch Reformed Church Mission (DRCM) from the Cape Colony was founded in 1889 in central Nyasaland amongst the Ngoni and their Chewa subjects and over the next few years missions were planted by a plethora of Protestant denominations. Only in 1902 were the White Fathers able to establish the first successful Catholic mission at Mua after being forced to abandon their mission established at Mponda in 1891 as a result of jurisdictional conflict between the British and the Portuguese, but though late starters they were well funded and expanded rapidly across the country.

On the heels of the first missionaries followed White traders and settlers who, from the 1870s onwards, began to acquire land from local chiefs. Europeans were able to alienate large amounts of land and mining concessions in a very short period of time. By 1891 Europeans claimed title to 15% of the land area of Nyasaland through the willingness of the chiefs to allow European to utilize the land. The usage rights did not imply ownership rights, which in customary law were inalienable, and that in exchange British protection from the endemic violence would be forthcoming. Since much of the land had its own inhabitants the settlers defined these as "tenants" who were required to pay "rent", not in cash or kind, but in the labour legitimated by the term “thangata”.

In the Ngonde Kyungu kingdom of the north the decentralizing tendencies described above led to a situation where the regional princes were virtually autonomous, paying little more than lip service to the monarchy by the mid-1880s, their power being founded on control of northern trade routes. The Ngonde were threatened from the west by the expansion of the Nyakyusa and the south by the Ngoni that had settled in the Kasito valley and who made periodic raids to extract cattle tribute from them. In around 1879 the Ngonde princes took advantage of the rebellion of the warlike Henga-Kamanga, Ngoni subjects, to settle the Henga-Kamanga on the northwest border as a buffer between themselves and the Nyakyusa. New Swahili settlements emerged in the last quarter of the 19th century. A post was established in the Luangwa valley among the Senga in the late 1870s that engaged in trade in slaves and ivory with the expanding Bemba chiefdoms of north eastern Northern Rhodesia.

In 1880 the Luangwa traders posted an agent named Mlozi on the Lake Nyasa shore to take advantage of the steamer operations of the Scottish run African Lakes Company. The new Swahili arrivals under Mlozi were welcomed by the Kyungu and his counsellors, the latter in reality controlling the former, since they opened new trade routes to rival those of the regional princes and brought weapons and military organization that could potentially be used to reduce the princes to tributaries once more and to repel potential raids by the Ngoni. The regional princes worked to counter the power of the Kyungu's court by wooing both Mlozi in the south and the African Lakes Company representatives in the north. The African Lakes Company included as part of its raison d'être the facilitation of Christian mission work at Bandawe, adding a new complicating element to the situation.

Mlozi was able to consolidate his power rapidly through alliance with the Henga-Kamanga, creating a network of trading stockades, and in 1887 proclaimed himself Sultan of the Ngonde. The expansion of Swahili power, the predatory activities of Swahili caravans and the increasingly independent raiding activities of the Henga-Kamanga were viewed with misgiving by the Ngonde princes, the traders of the African Lakes Company and the missionaries of Bandawe, the latter being especially concerned with the slave trading activities that continued illicitly across Lake Malawi. Moreover, relations between the Ngondi and the Nyakyusa had improved as a result of trade and the Ngoni military threat had subsided so that the Swahili and Henga-Kamanga had become military liabilities rather than assets, while direct trade with the Europeans, with whom the princes had formed warm relations, further reduced the value of the Swahili traders. Attempts by one of the Ngondi princes to eliminate the Henga-Kamanga through a general massacre in 1887 failed when the Swahili who were to execute the plan betrayed it instead and the conflict escalated into a war that drew the African Lakes Company in on the side of the Ngondi against the Swahili and the Henga-Kamanga, which culminated in the defeat of the latter by mid 1889.

The increasing presence of Presbyterian missionaries throughout the territory, their conflict with the Muslim Swahili as conductors of slave raids and as religious competitors and the intrusion from the south by their accomplices in the slave trade, (Catholic) Portugal, led to an orchestrated campaign in Scotland to pressure the British government to intervene in the territory. The British government had been reluctant to incur any costs in southern Africa was so swayed by an offer by Cecil John Rhodes in 1889 that his British South African Company would undertake the cost of the administration of the territory for three years in exchange for a Royal Charter providing it rights to occupy and exploit Southern and Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Thus reassured, the British government pressured the Portuguese to withdraw their troops from the Shirè Valley, where they were in any case experiencing fierce resistance from the Kololo, and to negotiate a settlement with the British that permitted the latter to annex the territory in May 1891 as the British Central African Protectorate.

The slave routes in Nyasaland at the time of Livingstone's travels

The slave trade in Nyasaland spread over most of the country.

Nkhotakota is a port town among the Chewa descendants of the Maravi in the middle of Nyasaland on the shore of Lake Nyasa. Salim bin Abdullah, known as “Jumbe”, one of the Swahili-Arab slave traders set up his headquarters there in the 1840s. From here he organized his expeditions to obtain slaves and ship them across the lake to East African markets at Kilwa. About 20, 000 slaves were annually shipped by Jumbe. The captives were held there until they numbered 1,000, taken across the lake and then forced to walk for three to four months to Kilwa where they were sold.

Dr David Livingstone was a Scottish missionary and explorer. In 1861 he visited Nkhotakota and this was 20 years after his arrival in Africa. Here he saw the slave trade that was at its peak along the East Coast after international bans were curtailing activities on the West Coast. Livingstone was mortified in the way slaves were handled at the stockade and he described it as "a place of bloodshed and lawlessness". In 1864 he returned to Nkhotakota and met Jumbe. He was able to secure a treaty between Jumbe and Chewa Chiefs to stop slave trade and hostilities between them. However, the treaty did not last long as one of Jumde's Yao headmen succumbed to the influences of Makajira.

Another slave route was at Karonga, 450 km further north up the Lake Nyasa shore. Mlozi, another Swahili-Arab, settled in the trading centre and terrorized the Nkhonde people,seizing them as slaves for transport from Zanzibar. He organized surprise raids as far as Chitipa, 100 km inland and into Zambia. He also employed a number of the Swahili from Tanzania who accompanied him on these expeditions. It was estimated that 2,000 slaves came annually from the Luangwa valley in Northern Rhodesia. Mlozi came into conflict with African Lakes Company, formed by Scottish businessmen and brothers John and Fredrick Moir in 1878. The Moir brothers supplied transport and trade for the missions working in the country. The African Lakes Company and Mlozi fought each other. Mlozi, and his Awemba allies on the other, had been reasonably tranquil following Johnston's arrival in 1889 when Mlozi had signed a treaty promising to keep the peace but was rescinded within a few years.

The slave trade was active along the southern shores of Lake Nyasa into the Tete Province and Zambezi valley in Mozambique. Here the controllers of the route were the Mangochi Yao chiefs namely Mponda, Jalasi and Makanjira. These Yao chiefs terrorized the peaceful Nyanja, a branch of the Maravi people who lived in the Upper Shire and Southern shores of Lake Malawi. They captured them as slaves, plundering their property and disrupting their agricultural economy. They were sold as slaves to the Arabs on the east coast. Dr David Livingstone visited the compound of one Yao chief, Jalasi, where he witnessed the suffering of the captured slaves.

The other slave trade route passed through the southern highlands and was also controlled by the Yao chiefs. Nyezerera and Mkanda controlled the sub route passing between Mulanje Mountain and Michesi Hill in what is now Phalombe District. Two other Yao chiefs, Chikumbu and Matipwiri, controlled the sub route passing through the southern part of Mulanje Mountain. They terrorized the Nyanja people in the Shirè highlands and those of the Lower Shire valley. Dr David Livingstone witnessed the suffering of these people and burning of their villages as he was traveling along the Shirè River and around Lake Chilwa in April 1859.

Britain's commissioner destroys the slave trade in Nyasaland

Portugal had been the first European power to sail around the Horn of Africa in the search to find a route to secure spices from India. They subsequently took over natural ports in Sofala and Mozambique Island from Arabs and traded in the hinterland. A dream to link their colony in Angola in the west with Mozambique in the east encountered hurdles when the British South Africa Company secured a treaty with Lobengula and this resulted in conflict in Manicaland. There was also rivalry between Britain and Portugal in the southern region of Nyasaland.

Portuguese Serpa Pinto led an expedition into Nyasaland in 1885 and this was followed in  1888 by Antonio Cardoso. This prompted Britain to appoint Henry Hamilton Johnston “Harry” to be Her Majesty's Commissioner for British Central Africa in November 1888. His instructions were to suppress the slave trade by every legitimate means in his power and to evaluate progress being made by the competitors from Portugal. Johnston arrived in Blantyre in March 1889. Johnston confronted Pinto in August 1889 near the confluence of the Shirè and Ruo rivers during a third exploration and it took until 1891 before final agreement was reached between Britain and Portugal for the borders of the British Central Africa Protectorate.

1888 by Antonio Cardoso. This prompted Britain to appoint Henry Hamilton Johnston “Harry” to be Her Majesty's Commissioner for British Central Africa in November 1888. His instructions were to suppress the slave trade by every legitimate means in his power and to evaluate progress being made by the competitors from Portugal. Johnston arrived in Blantyre in March 1889. Johnston confronted Pinto in August 1889 near the confluence of the Shirè and Ruo rivers during a third exploration and it took until 1891 before final agreement was reached between Britain and Portugal for the borders of the British Central Africa Protectorate.

To assist Johnston in the formidable task of terminating the Nyasaland slave trade, he had a small force of seventy one Indian soldiers from the 23rd and 32nd Sikh regiments and the Hyderabad Lancers, who had been seconded from the Indian Army for a three year tour of service, and ten Swahili police. The force was commanded by Captain Cecil Maguire of the Indian Army, brother of the Rochefort Maguire who had helped Rudd to negotiate the Concession from Lobengula. Its armament consisted of Snider rifles, two 9 pounder and one 7 pounder cannon, and a Maxim gun. The cost of maintaining this force came out of the allocation of up to £10,000 that was provided by the British South Africa Company. Cecil Rhodes was as anxious as Johnston to bring peace to Nyasaland. Livingstone’s anti-slave trade activism was gaining traction.

Johnston commenced operations during 1890 but the complexity of this role is best described in his own words in a report to the Foreign Office dated 24th November, 1891: "I feel bound to make our Protectorate in Nyasaland a reality to the unfortunate mass of the people who are robbed, raided and carried into captivity to satisfy the greed and lust of bloodshed prevailing among a few chiefs of the Yao race which is being unceasingly incited to engage in internecine war or slave raiding forays by the Arab and Swahili slave traders who travel between Nyasaland and the German and Portuguese littoral.

"Wherever it is possible by peaceable means to induce a chief to renounce the slave trade I have done so, and a considerable number of the lesser potentates have been brought to agree to give up adjusting their internecine quarrels by resort to arms, to cease selling their subjects into slavery and to close their territories to the passage of slave caravans. Their agreement, however, was in most cases a sullen one and their eyes were turned to the nearest big chief to see how he was dealt with. If he also accepted the gospel of peace and goodwill towards men they were ready enough to co-operate; but if the powerful potentate - the champion man of war of the district - held aloof and preserved a watchful or menacing attitude towards the Administration by ignoring or rejecting our proposals for a friendly understanding, then the little chiefs began to relax in their good behaviour and once more to capture and sell their neighbours' subjects or to allow the coast caravans with their troops of slaves bound for Kilwa, Ibo or Quilimane to pass through.

"Consequently I soon realized that certain notabilities in Nyasaland would have to be compelled to give up the slave trade before our Protectorate could become a reality."

The first of his targets to receive attention was the Yao chief, Chikumbu, who for some years had been raiding the mission caravans between Blantyre and the Upper Shirè and had now settled down on Mount Mlanje to a steady career of slave trading. Chikumbu and his people were aliens from the north who had imposed themselves on the local people, and the principal local chief, Chipoka, had sought the Queen's protection to prevent his country from being completely dominated by the Yaos. Chikumbu, however, was not concerned. Europeans passing through his territory were maltreated and robbed and one Englishman, named Pidder, who could not afford to pay the "present" demanded by Chikumbu, was flogged and put in the stocks. Mr Fred Moir of the African Lakes Corporation gathered a force of Europeans and natives and marched to Bidder's rescue, but came to a halt when Chikumbu threatened that unless they did so he would cut Pidder's head off. Fortunately, with the help of some friendly natives, Pidder managed to free himself and escape.

Chikumbu then began to threaten the lives of some British planters who with his permission had settled in or near his territory, and their position became critical. Johnston sent Maguire with a force of fifty Sikhs to discipline Chikumbu, and they reached his town on 21st July 1890. They were repeatedly attacked by the Yaos and during the fighting the Church of Scotland mission house was burnt down. The next day, however, Maguire captured Chikumbu's town and defeated his forces. A large number of slaves found in the town were released. The chief was badly wounded in the fighting and disappeared. His people were told that they could return to their homes provided they undertook to keep the peace, and in the absence of Chikumbu they settled down quietly. The missionaries rebuilt their house and extended their work among them, and more European settlers acquired estates for the cultivation of coffee.

Johnston next turned his attention to the slave raiders in the vicinity of Lake Nyasa and Lake Shirwa. Here again the Yao chiefs were the culprits, encouraged by the Arab and Swahili ivory merchants wanting slave porters. The principal villain in this region was Makanjira, who had repeatedly carried off boats from the Universities Mission stations on the east shore of Lake Nyasa and on one occasion had murdered a native boatman employed by the Mission. Mr Buchanan, Her Majesty's Acting Consul, had been flogged two years before. Makanjira had been quite unrepentent and had ignored Johnston's demand for ten tusks of ivory as a fine for the insult.

Setting out from Zomba at the end of September, 1890, with the Indian contingent of the British Central Africa Police, Johnston decided to take action against Mponda, a powerful Yao chief on the Upper Shirè, whose district was on the way to Makanjira's. Mponda was fond of raiding his neighbours and selling them as slaves. When the little force marched through Liwonde's area they received a cool reception, for it lay on one of the great slave routes of Africa - from the Angoni country west of the Shirè and Lake Nyasa and through the territories of Liwonde and Kawinga where they crossed the Shirè and then round the northern and southern ends of Lake Shirwa and so to the coast. Liwonde's country was full of Arabs and coastal people connected with the slave trade, and they resented the advent of a force that threatened their way of life. Liwonde was like putty in their hands. He would have been a good native chief had it not been for his taste for pombe, the heady native beer made from millet and maize.

Johnston was not concerned with Liwonde, however, and marched up the west bank of the Shirè until he came opposite Mponda's town, about a mile in length, and about three miles below Lake Nyasa. One of the reasons for Johnston's desire to deal with Mponda was that a local chief, Chikusi, had appealed to him for protection against the slave raider. As a gesture of defiance Mponda had beheaded fourteen of Chikusi's people who had not been sold to the slavers and had stuck their heads on posts round his stockade, which was already decorated with the skulls of at least a hundred other victims. When Captain Maguire visited the town the day after their arrival the blood of Chikusi's people still stained the ground.

Johnston's arrival had caught Mponda unprepared. The chief immediately began mustering his forces, but the work of mobilization went slowly. In the meantime Johnston and his force were busy fortifying their position. Captain Maguire designed a fort and in six days Fort Johnston was established. It was a circular redoubt with an internal diameter of ninety feet. The centre was occupied by a low circular house used as a provision store and cooking place. The magazine, on the side nearest the river, was dug partly underground and protected by a strong platform of earth heaped over a stout wooden framework. On this platform, which was about eight feet above the level of the fort, a sentry was stationed day and night, looking over the immense stretch of flat plain towards Lake Nyasa. The fort was defended by a rampart of bamboo and sand, surrounded by a deep ditch. It was a secure position.

But trouble suddenly faced Johnston from another direction. A slave caravan bound for Kilwa had recently arrived in Southern Nyasaland and had rested at Makanjira's for a few days before being ferried across the Shirè to Mponda's in one of Makanjira's dhows. The dhow had been caught in the act by the Universities Mission steamer, Charles Janson, who reported the incident to Johnston. A Yao chief, Chindamba, who had called upon Johnston to mediate between him and Mponda, changed his attitude. Like other local chiefs he wanted to sell all the slaves he could lay hands on while the Kilwa traders were in the area in return for cotton goods and gunpowder, and he resented Johnston's obvious intention to upset the trade. When Johnston sent two Swahili police to him with a message he imprisoned both of them. To prevent a league of hostile Yao chiefs being formed against him, Johnston decided to punish Chindamba immediately and sent Maguire and a force of sepoys and Zanzibaris to free the two Swahili. They succeeded, and then drove Chindamba's people into the hills and destroyed part of his town.

Mponda's reaction was typically African. As soon as he knew that the police had attacked Chindamba, he gathered all his canoes and ferried a force of some two thousand men across the Shirè. Johnston thought, logically, that Mponda was about to attack his depleted force, but instead Mponda had welcomed the opportunity to deal his old enemy, Chindamba, a crushing blow. Since most of the latter's men were in the hills they had no difficulty in capturing the women and children in the outlying villages, and started taking them back across the Shirè to be sold as slaves.

Mponda crossed the river to congratulate his men and Johnston remonstrated with him, demanding that the women and children be released at once. Mponda found himself in a quandary. His men were flushed with success and he had no control over them, and at the same time he was in no position to defy the Commissioner. He asked for three days' grace. "When my men are drunk with pombe I will take the slaves away and send them to you," he promised Johnston. The three days passed with no sign of the captives being surrendered. Johnston issued an ultimatum that unless the slaves were delivered by nine o'clock that evening he would attack the town. At nine o'clock he waited another hour, and then gave the order to fire. Captain Maguire fired incendiary shells from the 7 pounder and set most of Mponda's town on fire. Early next morning the sepoys crossed the river, drove the Yaos out of town and destroyed the stockades.

On 22nd October 1890 Mponda handed over Chindamba's people and also a large number of Angoni and other slaves who were to have been sold to the Kilwa traders. Three days later he came over to Fort Johnston and signed a treaty abolishing the slave trade in his territory. Chindamba and a number of other chiefs followed his example, promising to amend their ways and to support the efforts of the Administration to maintain law and order.

Captain Maguire pursued the Kilwa traders, captured seven of them and released 165 slaves. He took the slave sticks off the women, put them on to the slavers' necks and marched them back to Fort Johnston. Altogether the slaves rescued from the caravan and released at Mponda's numbered 268. Some of them had come from the Luangwa Valley, nearly three hundred miles to the west.

Mponda's troubles were not yet over. The seven Kilwa traders managed to escape and made their way to Makanjira, who was furious when he learnt that Mponda had decided to tread the path of virtue. He threatened that unless he renewed his war against the British he would descend on him with five dhows.

Johnston decided to tackle Makanjira. On October 28 he embarked his force on the African Lakes Corporation steamer, Domira, to sail up the Shirè and attack Makanjira's town the following afternoon. It extended for over a mile along the shore and had a population of six thousand. "It consists of the best houses we have met with in this part of Africa," wrote Johnston, "owing to the large number of slave traders and foreigners connected with the trade who have settled here because Makanjira's dhows give him a monopoly of the transport of slaves across the southern end of Lake Nyasa".

Makanjira's men opened fire on the steamer as soon as it approached the shore, and Maguire replied with incendiary shells from the 7-pounder which set the town alight in four places. Johnston and thirty-four sepoys boarded the barge which had been towed behind the steamer and landed on the west side of the town while Maguire bombarded the eastern side. When it became too dark to serve the gun Maguire landed in the Domira's boat with six men and made straight for two guns in the hands of the slavers. He captured them and before withdrawing set fire to a new dhow that was almost ready for launching. Next day Maguire renewed his attack on the town, defeated the Yaos in a pitch battle, saw to it that the town was completely burnt to the ground and also destroyed another two dhows, all for the loss of three men severely wounded.

Another notorious slave trader was Kawinga, a powerful Yao chief who lived on the north-west shore of Lake Shirwa and commanded an important slave route to the coast. In 1889 he was reputed to have sent as many as a thousand slaves to the markets at Kilwa and Quilimane. He had signed a treaty with John Buchanan when he was Acting Consul (before Johnston's arrival) putting his territory under British protection and promised to give up slavery. But he had slipped back into his old ways. Johnston sent Buchanan to see him with an escort of Captain Maguire and thirty sepoys. They were attacked by a subsidiary headman and there were casualties on both sides, but they destroyed the headman's village and Buchanan made it clear to Kawinga that he was serious. Kawinga was duly repentent and paid a fine of five tusks. In return Johnston sent him wheat, oats and barley and twelve different kinds of vegetable seeds and urged him to go in for agriculture.

Reporting to the Foreign Secretary on the results of four months' continuous campaigning against the slavers in Southern Nyasaland (up to November, 1890), Johnston was inclined to be prematurely jubilant. "It will soon become patent to the unscrupulous rascals of the East African littoral, from Kilwa to Quilimane, that slave trading in the Shirè province is a dangerous and unprofitable pursuit. We have also brought the powerful Yao chiefs to accept British domination, except the irreconcilable Makanjira who will probably remain an implacable but I hope impotent foe for the rest of his days. But appearances tend to show that there will be important defections from his rule and it is not unlikely that in time his own people may eject him from power when they find friendship with the British more profitable than enmity."

Johnston had by no means finished with Makanjira. The stage was set for tragedy.

Soon after Johnston and Maguire had returned to Zomba they received news that Makanjira was planning to attack the garrison at Fort Johnston. They took the threat seriously and decided to reinforce the garrison, complete the defence works and replenish the ammunition supplies. Maguire insisted on starting immediately to finish the work before Christmas.

When he reached Fort Johnston Maguire received word from a Yao chief, Kazembe, who had promised to do all he could to stop the slave trading, that he had detained a slave caravan of one of Makanjira's raiders, Saidi Mwazungu, a Swahili half-caste from Kilwa, and would hand it over to the British. But Maguire must first destroy two of Makanjira's dhows which were preparing to attack him for helping the Administration. Maguire at once set off with thirty sepoys and six Zanzibaris, accompanied by the Parsee surgeon to the Indian contingent, Dr Boyce.

With a guide provided by Kazembe to show them where the dhows were hidden, the force crossed the Lake in the Domira to a point on the south-east shore about ten miles north of Makanjira's main town which had been destroyed at the end of October. The approach to the shore was a twisting channel between rocks and sandbanks. A wind sprang up and the waves became alarmingly rough. Maguire could see the dhows and was determined that they should not be left unscathed. He ordered his troops into the Domira's barge and made for the shore, but it was driven on to a sandbank. Maguire and his men jumped out and waded for some distance to the dhows, which were in a sheltered cove. They were hotly attacked by Makanjira's men hidden among the rocks and reeds of the shoreline, but pressed on to the dhows. One was set on fire and the other badly damaged before Maguire, seeing a large force of Makanjira's men streaming down to the beach, called off the attack and waded back to the barge. But in their absence the barge had been lifted off the sandbank by the storm and dashed to pieces on the rocks.

All this time Maguire and his men were exposed to a continuous hail of bullets from the shore, and three sepoys were killed. Maguire signalled to the Domira to launch the dinghy and although it was repeatedly swamped he managed to get most of his force on board. He and the rest started to wade out to the steamer. They were about ten yards from it, and in deep water, when, just as Maguire reached out to grasp a rope thrown to him by the ship's engineer, MacEwan, a bullet struck him in the head and killed him instantly.

MacEwan and eight of the sepoys tried to reach his body. But the worsening storm increased to gale force and they had to give all their attention to the ship. The Domira, was torn from her anchorage and driven on to a sandbank near the shore. At this point the rope that had been thrown to Maguire wound itself round the propeller and stopped the engines. The vessel drifted into shallow water and was swept by fierce fire from the beach at close range. The sepoys put up a barricade of bags and bolts of cloth on the landward side of the ship and this gave them little protection. The captain, Mr Keiller, was severely wounded in the head on the first day. On the second day MacEwan was wounded in the thigh and the second engineer, Urquhart, in the face.

The Domira lay in this terrible predicament for six days, from December 15 to 20, and all the time those on board were exposed to fire from the beach. On the morning of the 18th their attackers proposed a truce and offered, in return for sixty lengths of calico, to send sixty men to help get the steamer off its sandbank. But they insisted that two of the white men should first come ashore to draw up a peace agreement.

Dr Boyce at once offered to go. After the day of the storm the waves had washed Maguire's body on to the beach and there it had lain exposed for five days, with near it the bodies of the three sepoys who had been killed. Boyce had a strong personal regard for Maguire and wanted to give him a decent burial. MacEwan agreed to go with him in spite of his wounded thigh, and they went ashore with an escort of three Swahili police and three Anyanja steamer boys. They were taken to a house where they understood the negotiations were to be held, and there they waited for over an hour. Messengers had been sent to Makanjira to tell him that the deputation was waiting to see him. They returned with the order that the whole party was to be killed, and it was carried out at once. MacEwan was shot in three places and Dr Boyce, the three Swahili police and two of the steamer boys were speared to death. The third steamer boy managed to escape and hide in dense reeds on the shore until he was able to wade out to the Domira and tell them of the massacre.

The two remaining Europeans, Keiller and Urquhart, knew that their survival depended entirely on their own effort. During the next two nights, with the aid of the sepoys and Swahilis on board, they toiled unceasingly to get the steamer off the sandbank by digging under her keel and laying out anchors. On the night of the 20th the Domira floated off the bank into deep water. They quickly got up steam. As they drew away from that terrible shore the Indian gunners loaded the 7-pounder with an incendiary shell, took careful aim at the nearby village where Makanjira's men were noisily celebrating, and put the shell in their midst. The rejoicings abruptly ended.

The loss of Captain Maguire was a heavy blow to the Commissioner. He thought very highly of him, both as an officer of considerable ability and as a man of character and charm. Johnston named a point on the south-east coast of Lake Nyasa near the Portuguese border, Fort Maguire in his memory.

His death was not in vain. It induced the Foreign Office to prevail upon the Admiralty to provide three gunboats for service on the Upper Shirè and on Lake Nyasa to deal with the slave dhows. They arrived in 1892 and worked in co-operation with a steamer that had also been placed on the lake by the German Anti-Slavery Society and was called the "Hermann von Wissman" after the leader of the German expedition. These measures were effective in checking the immense traffic in slaves from the regions west of the Lake, and particularly along the middle course of the Luangwa River which Johnston estimated provided the slavers with more than two thousand victims every year. The ships made it difficult for them to be ferried across the Lake in dhows, and the establishment of Fort Johnston at the southern end of the Lake closed the route through Mponda's country.

But there was plenty of trouble elsewhere. Travellers on the road from Blantyre to Zomba were liable to robbery at the hands of the Yaos living in the vicinity of Chiradzulu, and no one was safe on the route through Mlanje Mountain to Portuguese territory and the east coast. The establishment of Fort Lister at the northern and Fort Anderson at the southern end of the range curbed their activities, but it took some time to convince the Yao chiefs in this region that crime did not pay. The Yaos on the Upper Shirè, inspired and led by Liwonde, were another thorn in the Commissioner's side. In the campaign against him the plucky little "Domira" again found herself in an unenviable position when she went aground in the Shirè opposite one of Liwonde's towns and the crew was trapped in the fire between defenders and attackers. The arrival of reinforcements for the Administration's forces relieved the position and Liwonde's capital town was captured and burnt down. The chief himself escaped, however, and he gave occasional trouble for the next few years.

The original contingent of Indian soldiers who had given valiant service returned to their homeland at the end of their three-year period and were replaced during 1893 by two hundred Sikhs. At the same time the Zanzibaris who had formed part of the police force were disbanded and replaced by Atonga from West Nyasa and Makua tribesmen from Portuguese East Africa. As time went on Johnston recruited more and more natives from the recognized fighting tribes as these became pacified to assist him preserve law and order.

The main trouble spot during 1893 was Nkhotakota, on the western shore of Lake Nyasa, which was a sultanate originally established by the Sultan of Zanzibar and ruled by an independent potentate called the Jumbe. Puffed up by his victory over Captain Maguire, which because of his preoccupation with more urgent matters in other parts of the Protectorate Johnston had had to leave unavenged, the troublesome Makanjira attacked the Jumbe, who was friendly to the British, and by the middle of 1893 had captured most of his territory until the Jumbe was penned in Nkhotakota itself. He was having difficulty holding out, and since the gunboats were now ready Johnston decided that the time had come to settle accounts.

The first objective was to take the Jumbe. The Yao headmen who had gone rogue was bombarded by Johnston and his Sihk soldiers five miles from the lake shore in 1894 and taken by storm and killed. Jumbe was tried and banished to Zanzibar.

The remaining relics along this slave route include a mosque which was the first to be constructed in the country, graves of three Jumbe chiefs and also the graves of the lieutenants of Jumbe. The fig trees where Jumbe and Dr David Livingstone met and agreed to stop slave trade still stood. Other features include the site where the slave market stood, the village of descendants of slave traders and slaves who were freed by the British, and also the Anglican Church was built to offer them education and Christianity.

The expedition then crossed the Lake and meted out similar treatment to Makanjira's town and a number of smaller towns and villages, including the village where Maguire, Boyce and MacEwan had met their deaths. Fort Maguire was erected on the Lake shore and garrisoned by Sikhs. Early in 1894 Makanjira attacked the fort but was defeated with heavy loss. His power at last was broken and he sought refuge in Portuguese territory.

The year 1895 saw success crown Johnston's grim, tenacious efforts to teach the slavers the error of their ways and win them over to the Administration. Matipwiri was an Arabised Yao who held the pleasant, well-watered country to the east of Mlanje and the Ruo river commanding the route from Lake Nyasa to Quilimane. He had grown rich by taking toll of the ivory exported to the coast and of the goods brought into Nyasaland, an African robber baron. When he heard that Matipwiri was planning to attack Fort Lister on Mlanje and the scattered European settlement in the vicinity of the mountain, Johnston took action against him in September, and Matipwiri surrendered unconditionally.

Another chief who had to be brought to book was Zarafi who dominated the territory to the east of the Upper Shirè and had long been an active slaver. Johnston set out with a force consisting of 65 Sikhs and 230 native soldiers commanded by Major C. A. Edwards. Their objective was Zarafi's capital on Mangoche Mountain, entailing a march of 78 miles from Zomba of which 50 were through enemy country. Porters were provided by friendly chiefs of the Mlanje district. Their conduct was admirable. Although repeatedly under fire they never once abandoned their loads or attempted to run away.

Mangoche Mountain was a great ridge about twelve miles long and a mile broad and rose to 5,500 feet at its highest point. It was difficult country, ideal for ambush, but two guides provided by a rival chief, Kawinga, led the force by a little known route to within fifteen miles of Zarafi's town. The first attack came when they entered a wooded gorge leading up to the south-eastern base of the mountain, and the fire was directed chiefly against the porters. The fire was wild and none of the porters was hit but an Atonga soldier was wounded. A charge by the Atongas, led by Major Bradshaw and Captain Cavendish, scattered the enemy before they could reload.

Shortly afterwards the force reached a natural castle of rocks crowning a hill which dominated the route. Zarafi had expected them to come from another direction, and the castle was unoccupied. As soon as he discovered his error he sent a large body of men to defend the hill. Not knowing that the police had already arrived they advanced openly and suffered many casualties. The porters rested at this spot while Major Edwards and the majority of his force pushed on for three miles along the ridge. The terrain was all in the enemy's favour - steep hillsides and enormous boulders from behind which Zarafi's men poured a galling fire on the soldiers toiling up the narrow path. Casualties, however, were few because most of the natives aimed too high and the damage was done by a few good marksmen armed with Snider rifles. The officers with the force who were armed with Lee-Metford rifles did great execution and killed about thirty-five of the enemy, whose total losses before the day's fighting ended was more than a hundred men. As a result of this encounter the police seized another favourable position for the final assault on Zarafi's stronghold, but the enemy gave them no rest. Snipers got busy and both Johnston and Major Edwards had narrow escapes, but the 7-pounder was brought into action and cleared the hillsides.

Before dawn the next morning (October 28, 1895) the police climbed Mangoche Mountain without losing a single man. The enemy was completely routed and Zarafi's town was captured without difficulty. Zarafi had already fled, having taken the precaution of sending his ivory, cattle, most of his women and his reserve gunpowder to a Yao chief in Portuguese territory for safe keeping. Only a few slaves were found in the town, and Johnston was disappointed to learn that a large number of slaves had been sold to caravans bound for the coast a few days before. There was very little loot, but one item which pleased Johnston greatly was a 7-pounder gun which Zarafi had captured from a small force sent against him three years previously, one of the few defeats suffered by his police in six years of almost incessant campaigning. The gun was a welcome addition to his armament.

The bulk of Zarafi's people were of Anyanja stock who had been dominated by the Yaos. Now that most of the Yaos had fled with Zarafi to their original homeland beyond the Portuguese border, the local people returned and settled down quietly in their old homes. The power of another Yao tyrant had been broken.

The north end of Lake Nyasa, which had been the scene of so much bitter fighting between the African Lakes Corporation on the one side and the Arab half-caste, Mlozi, and his Awemba allies on the other, had been reasonably tranquil following Johnston's arrival in 1889 when Mlozi had signed a treaty promising to keep the peace and at Johnston's request had destroyed an Arab fort, known as Mselemu's stockade, which had commanded the Stevenson road to Lake Tanganyika. But towards the end of 1894 the trouble flared up again. Two large villages which provided porters for the African Lakes Corporation's traffic on the Tanganyika road were attacked by the Arab slave traders and the Awemba, and the occupants were almost entirely exterminated. They also blocked the road with tree trunks and began rebuilding Mselemu's stockade in open defiance of the 1889 treaty.

The unrest in the area affected the adjacent German territory of Tanganyika and the German commandant placed a steamer at Johnston's disposal to help him deal with the insurgents. The missionaries and the agents of the African Lakes Corporation, fearing attacks on their stations, urged the Commissioner to take immediate action to end the trouble, and the trusty little Domira was again employed as a troopship.

The North Nyasa Arabs had overreached themselves. They were up against an entirely different adversary now. Six years before they had had to contend with gallant amateurs assisted by unreliable native allies, all of them inadequately armed. Now they found themselves attacked by disciplined troops, capably led by professional officers and armed with modern weapons. The attack on the Arab forces was launched on December 1, 1894, and after two and a half days' fighting was completely successful. All the stockades were taken and destroyed. The principal culprit, Mlozi, was captured. During the fighting in and around Mlozi's stockade, the Arabs lost more than two hundred men, against Johnston's losses of one European officer severely wounded, one Indian and three native soldiers killed and six Indian and four native soldiers wounded. They released 569 slaves. The Arabs had intended to make a big stand at Mlozi's and had turned the town into a powder magazine. Early in the fighting the house in which the gunpowder was stored was hit by a shell, with satisfactory results. Mlozi was tried by the Nkhonde chiefs and hanged.

Johnston has given an interesting description of Mlozi's town as typifying the stockade erected by the leading slavers. It covered an area of just over twenty acres and was surrounded by walls in which there were five gateways. The outer wall, eight feet high, was made of logs planted firmly in the ground and almost touching, wattled with strong twigs and plastered inside and out with mud until the total thickness of the wall was about two feet. Parallel with the outer wall and about twelve feet away from it was another similar wall seven feet high. The space between them formed a gallery which was roofed over and divided into partitions by wattle and mud walls every twelve feet. The roof was made of two layers of logs on which grass was spread and then two feet of mud well beaten down. The total circumference of the walls was 1,160 yards.

One last wrong remained to be righted - the treacherous murder of Boyce and MacEwan during Captain Maguire's ill-fated attack on Makanjira's dhows. Makanjira himself had been driven out of Nyasaland, but there remained the man primarily responsible for the treachery that had led to their murder, Makanjira's lieutenant, Saidi Mwazungu. After the final overthrow of Makanjira he had sought refuge with the notorious Angoni slaver, Mwasi Kazungu, in the Marimba district. Many of Makanjira's fighting men had joined Saidi and he had built a strong stockade in Kazungu's country. With a loyalty typical of the Arab slave trader, Saidi was conspiring with Angoni chiefs to the north and south and with the Mohammedans at Nkhotakota to take control of his benefactor's territory, after which he proposed to attack Nkhotakota, where the Jumbe was friendly to the British, and drive the garrison into the Lake.

Johnston soon spoilt this little plan. He sent a strong force in December, 1895, and after some severe fighting the conspirator's forces were routed. Saidi Mwazungu was captured and the foul crime committed five years before was avenged.

In a letter to Lord Salisbury dated January 24, 1896, Commissioner Harry Johnston was able to report that as a result of his actions "there does not exist a single independent avowedly slave trading chief within the British Central African Protectorate, nor anyone who is known to be inimical to British rule. Those enemies whom we have conquered, like all with whom we have fought since our assumption of the Protectorate, were not natives of the country fighting for their independence but aliens of Arab, Yao or Zulu race who were contesting with us for the supremacy over the natives of Nyasaland."

The traffic in human flesh and blood from Nyasaland had ended.

References

Beck, Sanderson, 2010. Mideast & Africa 1700 – 1950. Ethics of Civilisation, Volume 16.

Bone, D S, 1982. Islam in Malawi, Journal of Religion in Africa, 13(2), 126-138.

Chisholm, Hugh, 1911. Serpa Pinto, Alexandre Alberto de la Rocha. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol 24 (11th ed). Cambridge University Press.

EISA, African Democracy Encyclopaedia, 2010. Malawi: Invasions from all sides - the Swahili to the British (1800-1891).

Kalinga, O J M, 1980 "The Karonga War: Commercial Rivalry and Politics of Survival", Journal of African History, 21(2), 209-218.

Kalinga, O J M, 1983. Cultural and Political Change in Northern Malawi c. 1350-1800, African Study Monographs, 3, March, 49-58.

Kalinga, O J M, 1984. Towards a Better Understanding of Socio-Economic Change in 18th- and 19th-Century, Cahiers d'Études Africaines, 24(93), 87-100.

Langworthy, H W, 1971. Swahili Influence in the Area between Lake Malawi and the Luangwa River, African Historical Studies, 4(3), 575-602

Livingstone, David (1857). Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa: Including a Sketch of Sixteen Years' Residence in the Interior of Africa. London: Murray.

Maritime Heritage, 2017. Mozambique. Maritime Nations.

McCracken, John (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859-1966. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.

Newitt, M. D. D. (1995). A history of Mozambique. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

Nowell, Charles E. (1947). Portugal and the Partition of Africa. The Journal of Modern History. University of Chicago Press. 19 (1): 1–17.

Pike, John (1968). Malawi: a political and economic history. London: Pall Mall P. rhodesia.nl. Fighting the slavers. www.rhodesia.nl/Slavers

UNESCO, World Heritage Convention. Malawi Slave Routes and Dr David Livingstone Trail