History of Portuguese East Africa, and Rivalry between Britain and Portugal in Southern Africa in 19th century

Early history of Portuguese East Africa and the hinterland

Mozambique is best known for its extensive coastline, fronting the Mozambique Channel, which separates mainland Africa from the island of Madagascar, offering some of Africa’s best natural harbours. These have allowed Mozambique an important role in the maritime economy of the Indian Ocean.

Bantu tribes moved into the area, part of which is now Mozambique, from central and west Africa during the third century. The 11th century Empire of the fore-bears of Shona, the main ethnic group in modern Zimbabwe, extended into part of Mozambique.

Much of the historical data for this period comes from the records of Arab and Indian traders in the region in the 10th century. Settlements featured stone enclosures, and their inhabitants played an important role in intra-African trade to the west.

Over the next several centuries, traders from north eastern Africa and later from the Middle East and Asia arrived by sea, prompting ports along the Mozambican coast to flourish. Sofala, among the most prominent ports, developed as a trade centre for gold from the interior.

Commercial settlements also developed to the north of Sofala at Angoche, Mozambique Island, the Querimba Islands, and the mouth of the Zambezi River. Beads, cloth, and other goods brought by Arab and Asian traders attracted caravans of agrarian-based traders from inland Mozambique. They in turn distributed the goods to the African interior. A struggle for control of this trade developed, and it was soon won by the cattle-owning chiefs of the Karanga in the south and the Makua in the north. Slave trading was also common throughout this period, in both the coastal and interior regions.

Portugal was the first European power to take an active interest in the southern portion of the African continent before they had sailed there. A map of East Africa in 1460 showed a settlement as low down as at Sofala.

The new king in 1481, John II of Portugal, introduced many reforms. To break the monarch's dependence on the feudal nobility, he needed to build up the royal treasury; he considered royal commerce to be the key to achieving that. Under John II's watch, the gold and slave trade in West Africa was greatly expanded. He was eager to break into the highly profitable spice trade between Europe and Asia, which was conducted chiefly by land.

Bartolomeu Diaz set sail from Portugal in 1487 to find the sea route to India. Eventually in 1488 he rounded the Cape of Good Hope in a storm and probably struck land at the modern day Mossel Bay. He continued up the coast of Algoa Bay but had to return to Portugal after only a few days of exploration because of a mutiny.

Pedro da Covilhoa was then sent on an overland expedition from Alexandria to India and he was able to report on the geography of the east coast of Africa.

This enabled Vasco da Gama to sail with a fleet of four ships on 8th July 1497. On 22nd November he rounded the Cape and passed and named the coast “Natal” around Christmas. He reached Mozambique on 2nd March 1498. He spent four weeks in the vicinity of Mozambique Island that was under Arab control so he claimed to be Muslim but the locals became suspicious so he fled. The expedition resorted to piracy, looting Arab merchant ships that were generally unarmed trading vessels. They docked in the port of Mombasa from 7th April 1498, but were met with hostility and departed one week later. The port of Malindi was friendlier and a pilot was provided to assist with the passage to Calicut, India. The gifts that Da Gama brought were considered to be trivial, and failed to impress so he was treated like an ordinary pirate and not a royal ambassador. The King insisted that da Gama pay customs duty – preferably in gold – like any other trader. This strained the relationship so, annoyed by this; da Gama carried a few Nairs and sixteen fishermen off with him by force. Eager to set sail for home, he ignored the local warnings about monsoon wind at that time and set sail on 29th August 1498. This error resulted in the loss of two ships and only 55 out of the 170 sailors that had started out from Portugal returned home.

One significant result of Da Gama’s voyage was the colonization of Mozambique by the Portuguese Crown. Fundamentally ports were required by ships for the spice trade from India and slaves from the hinterland had to be transported.

Thereafter, Portuguese influence displaced the Arabs and Indians in the trading system in southern Africa in the 16th century but without direct access to gold they were at a disadvantage. The Portuguese gradually moved inland, usurping the local rulers but were unable to expand north.

The first white man that is known to have walked on Rhodesian soil was a criminal, Luis Fernandes, who disembarked on the Mozambique coast in 1514 with instructions to explore the hinterland. He faced native hostility, wild beasts, disease and accident. It is evident that Fernandes travelled on foot over most of Mashonaland and found signs of gold in the Que Que area. He duly caught his ship and returned to Portugal three years after he had been shipped out having earned his freedom by completing this journey.

The Portuguese gradually extended their control up the Zambezi Valley and north and south along the Mozambican coast. In 1727 they founded a trading post at Inhambane, on the southern coast, and in 1781 they permanently occupied Delagoa Bay, an important location farther south on the site of modern Maputo. Dutch and Austrian traders had briefly settled at Delagoa Bay but subsequently Portugal controlled the prosperous ivory trade with the nearby Nguni and Tonga chiefs.

At roughly the same time as the rise of the ivory trade, climatic changes and the rise of the slave trade had even greater effects on Mozambique. The trade in slaves, which had existed at a low level before the arrival of Europeans, continued throughout the colonial period, under the hand of African and European traders. By the late 1700s, however, demand for slaves had grown markedly in response to European colonization of Mauritius and Reunion. When prolonged droughts started in Mozambique in the 1760s and became endemic from the 1790s, crops failed, cattle suffered, chiefdoms faltered, and traditional patterns of long-distance commerce were disrupted. Banditry and slave raiding increased and large numbers of slaves were brought to the coast.

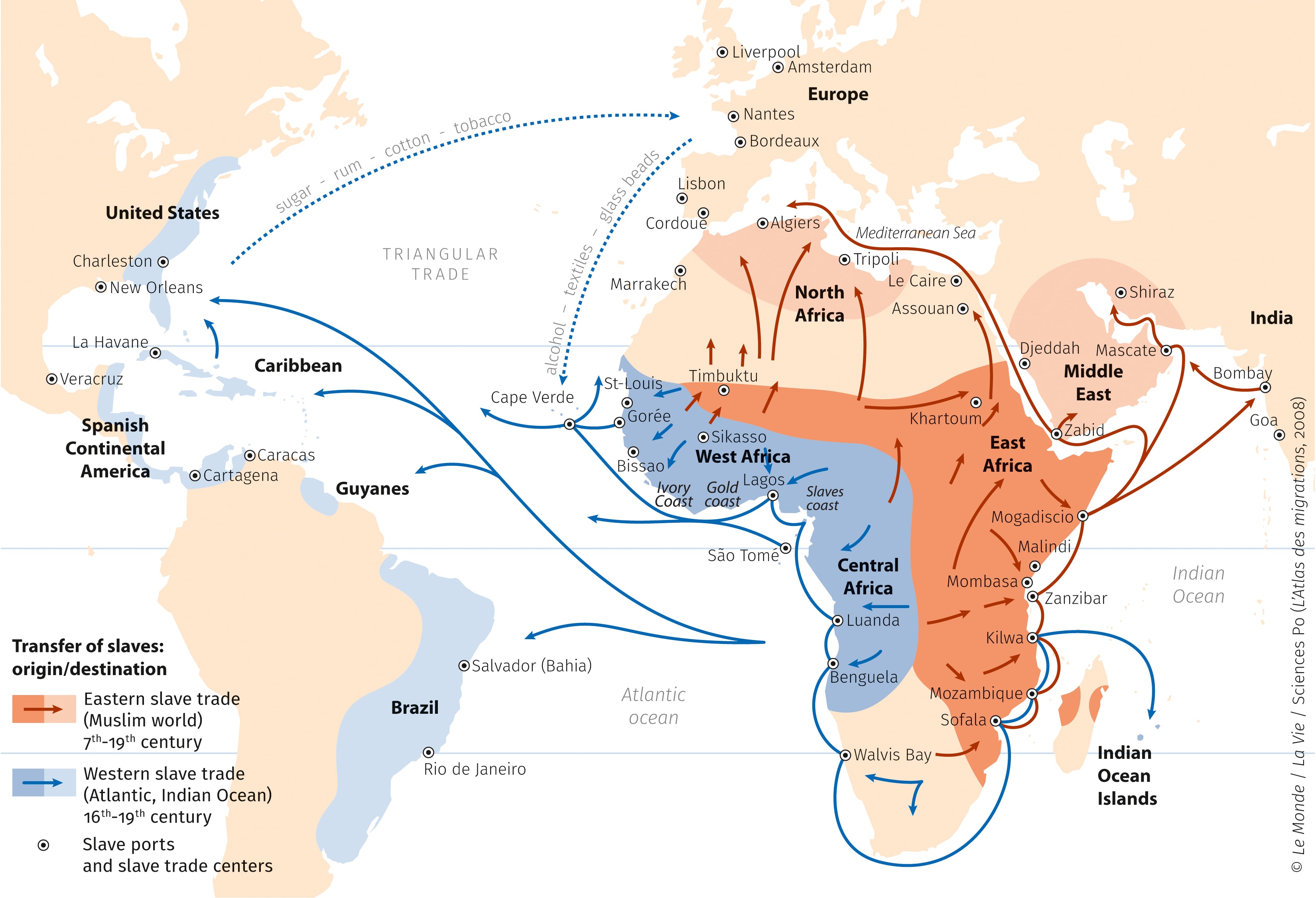

Slaves from the ports of Sofala, Mozambique Island and Kilwa were transported to both the Eastern slave trade to the Muslim world (red line) and to the Western slave trade of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans (blue lines).

The occupation of the British in the Cape in 1795 led Dr Francisco Lacerda to become concerned that the British would venture north and this could endanger the Portuguese dream to link their colony in Angola in the west with Mozambique in the east. He was appointed Governor of the Zambezi and lead an expedition from Mozambique to Angola with the objective of establishing Portuguese sovereignty from coast to coast. Lacerda died near Lake Mweru in October 1798 so the expedition returned to Tete without achieving its objective.

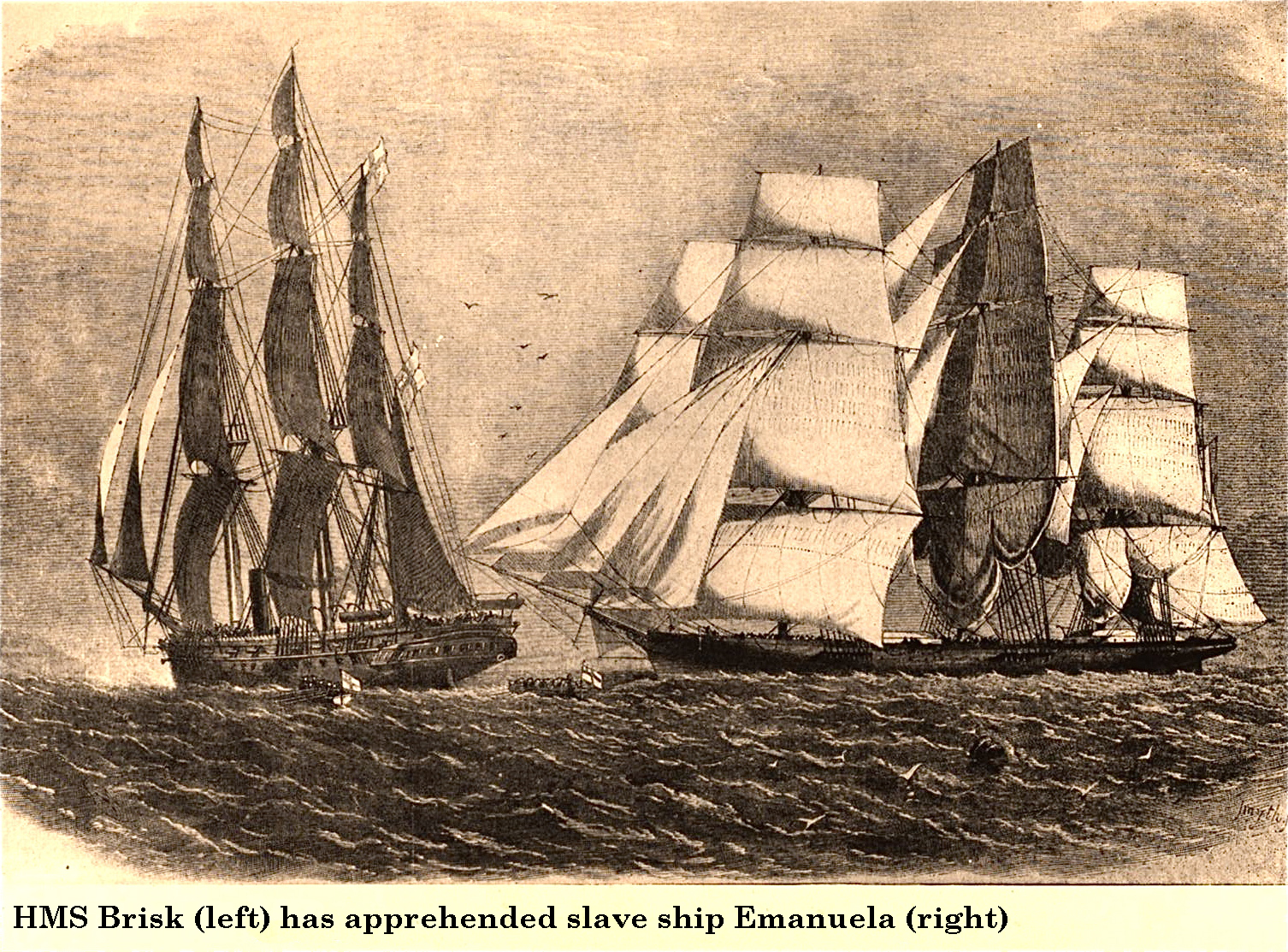

9,000 Africans were being exported as slaves from Mozambique every year in 1790. The  British abolished the slave trade in 1807 and efforts by the Royal Navy suppressed it in western Africa but insatiable demand stimulated the trade in eastern Africa. The numbers exported on the east coast rose dramatically, with approximately 1 million slaves exported from Mozambique during the 1800s as it continued for more than sixty years. Entire areas were depopulated, societies disintegrated and local economies collapsed in the interior. The independence of Brazil from Portugal in 1822 was a large drain to that power and led to renewed interest on the part of the Portuguese in their African possessions.

British abolished the slave trade in 1807 and efforts by the Royal Navy suppressed it in western Africa but insatiable demand stimulated the trade in eastern Africa. The numbers exported on the east coast rose dramatically, with approximately 1 million slaves exported from Mozambique during the 1800s as it continued for more than sixty years. Entire areas were depopulated, societies disintegrated and local economies collapsed in the interior. The independence of Brazil from Portugal in 1822 was a large drain to that power and led to renewed interest on the part of the Portuguese in their African possessions.

Around 1850 those glory-days of Portuguese imperialism from the late 15th century were long gone and the slave trade was virtually its salvation despite being officially banned in 1842.

A prolonged drought brought on famine in the early 1830s so during 1831 the Island of Mozambique was forced to import food from beyond the borders. The rise and expansion of the Zulu kingdom unleashed a series of migrating raiding groups across the sub-continent two of which penetrated Mozambique in the first three decades of the 19th Century. The Zulus killed and plundered as they passed through adding to the misery and economic chaos created by the slave trade and drought. One group under Zwangendaba swept through northwards, crossed the Zambezi and settled west of Mozambique while the other under Soshangane crossed the Limpopo eastwards and settled in southern Mozambique, creating the Gaza kingdom of the Shangaans. In 1833 the Shangaans captured the fort at Lourenço Marques. Succession struggles within the kingdom led to devastating civil wars.

At this stage, Scottish David Livingstone arrived in Kuruman at the age of 28. He had qualified as a doctor and minister. He travelled extensively throughout southern Africa as a missionary.

Lions often attacked herds of the Mabotsa villagers in Bechuanaland. On 16th February 1844, Mebalwe, a deacon, and Livingstone joined a hunt to control them. Livingstone got a clear shot at a large lion, but while he was reloading it attacked, crushing his left arm, and forced him to the ground. His life was saved by Mebalwe diverting its attention by trying to shoot the lion though he too was bitten. A man who tried spearing it was attacked just before it dropped dead from its wounds.

Livingstone's broken bone, even though inexpertly set by himself and Edwards, bonded strongly. He went for recuperation to Kuruman, where he was tended by Moffat's daughter Mary, and they became engaged. His arm healed, enabling him to shoot and lift heavy weights, though it remained a source of much suffering for the rest of his life, and he was not able to lift the arm higher than his shoulder.

Two African traders crossed from Angola to Mozambique around 1800 and two Arabs crossed the continent from Zanzibar, Tanzania to Benguela, Angola between 1853 and 1854. However, the first European to walk the entire coast to coast in fact was David Livingstone shortly after that. He departed from Linyati on 11th November 1853 and reached Luanda (then written as 'Loanda') at the end of May 1854 to commence the long crossing. He only departed in September on the coast-to-coast journey as he needed to recover from the 27 bouts of malaria he suffered during the journey west that almost killed him. Almost a year later he reached Linyati in August 1855 after travelling east then south then proceeded directly east along the Zambezi. He found the natives to be increasingly aggressive as he approached Tete and found out that the Portuguese had been hostile to the local tribes for the past two years but after explaining that he was British and by showing his lighter skin colour he was respected and given lifesaving assistance. He reached Tete on 3rd March and finally reached the coast at Quilimane on 20th May 1856.

Livingstone’s feat was only of interest because of the Britain/Portugal territorial rivalry and during his life he was better known as an explorer and antislavery campaigner. He may have converted fewer to Christianity through the missions that he operated than endless slaves whose suffering he ended.

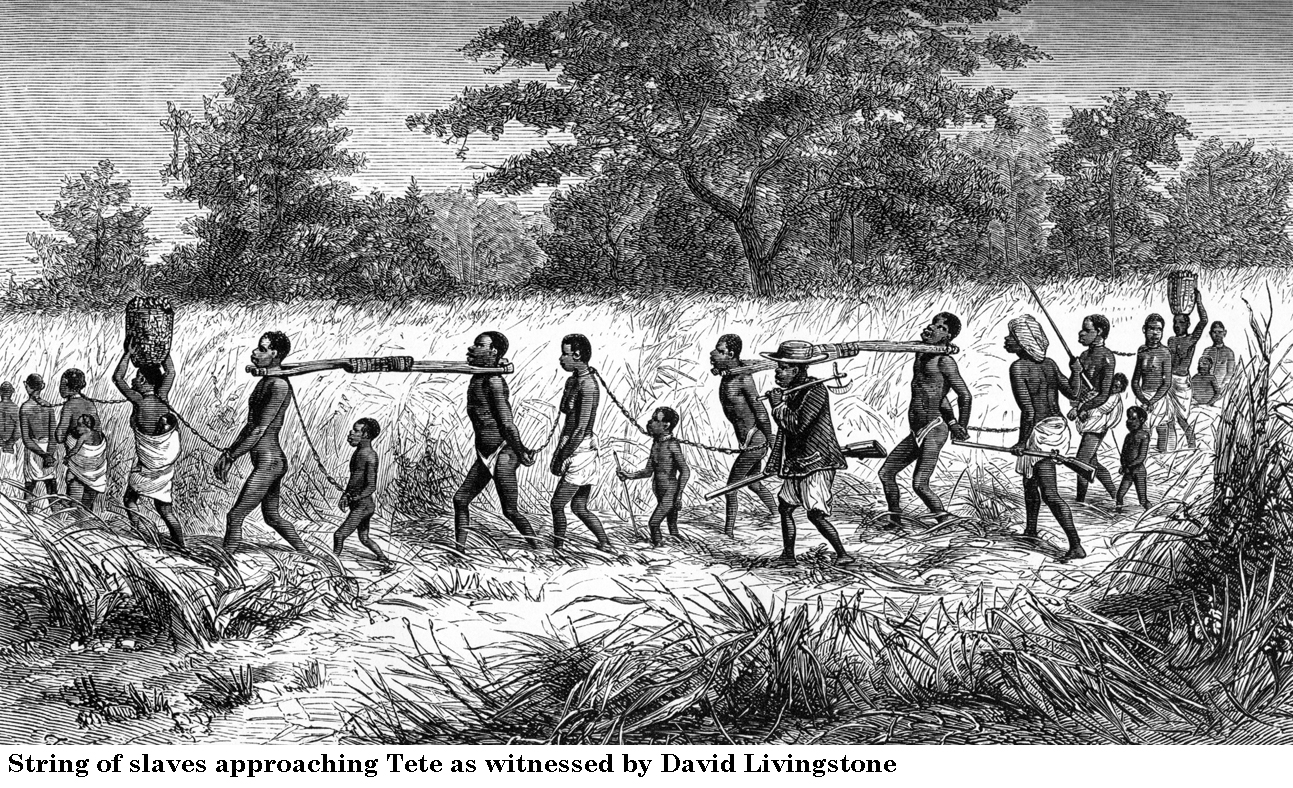

He relates this episode on his way to Tete. "Next forenoon we halted at the village of our  old friend Mbame, to obtain new carriers... After resting a little, Mbame told us that a slave party on its way to Tete would presently pass through his village... [W]e resolved to run all risks, and put a stop, if possible, to the slave-trade, which had now followed on the footsteps of our discoveries. A few minutes after Mbame had spoken to us, the slave party, a long line of manacled men, women, and children, came wending their way round the hill and into the valley, on the side of which the village stood. The black drivers, armed with muskets, and bedecked with various articles of finery, marched jauntily in the front, middle, and rear of the line; some of them blowing exultant notes out of long tin horns. They seemed to feel that they were doing a very noble thing, and might proudly march with an air of triumph. But the instant the fellows caught a glimpse of the English, they darted off like mad into the forest ... The captives knelt down, and, in their way of expressing thanks, clapped their hands with great energy. They were thus left entirely on our hands, and knives were soon busy cutting the women and children loose. It was more difficult to cut the men adrift, as each had his neck in the fork of a stout stick, six or seven feet long, and kept in by an iron rod which was riveted at both ends across the throat. With a saw, luckily in the Bishop’s baggage, one by one the men were sawn out into freedom."

old friend Mbame, to obtain new carriers... After resting a little, Mbame told us that a slave party on its way to Tete would presently pass through his village... [W]e resolved to run all risks, and put a stop, if possible, to the slave-trade, which had now followed on the footsteps of our discoveries. A few minutes after Mbame had spoken to us, the slave party, a long line of manacled men, women, and children, came wending their way round the hill and into the valley, on the side of which the village stood. The black drivers, armed with muskets, and bedecked with various articles of finery, marched jauntily in the front, middle, and rear of the line; some of them blowing exultant notes out of long tin horns. They seemed to feel that they were doing a very noble thing, and might proudly march with an air of triumph. But the instant the fellows caught a glimpse of the English, they darted off like mad into the forest ... The captives knelt down, and, in their way of expressing thanks, clapped their hands with great energy. They were thus left entirely on our hands, and knives were soon busy cutting the women and children loose. It was more difficult to cut the men adrift, as each had his neck in the fork of a stout stick, six or seven feet long, and kept in by an iron rod which was riveted at both ends across the throat. With a saw, luckily in the Bishop’s baggage, one by one the men were sawn out into freedom."

A less favourable outcome is related: “We passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body and lying on the path: a group of men stood about a hundred yards off on one side, and another of the women on the other side, looking on; they said an Arab who passed early that morning had done it in anger at losing the price he had given for her, because she was unable to walk any longer.”

On 27th June 1866: “Today we came upon a man dead from starvation, as he was very thin. One of our men wandered and found many slaves with slave-sticks on, abandoned by their masters from want of food; they were too weak to be able to speak or say where they had come from; some were quite young.”

This is how he summed up his feelings about slavery: “if my disclosures regarding the terrible Ujijian slavery should lead to the suppression of the East Coast slave trade, I shall regard that as a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together.”

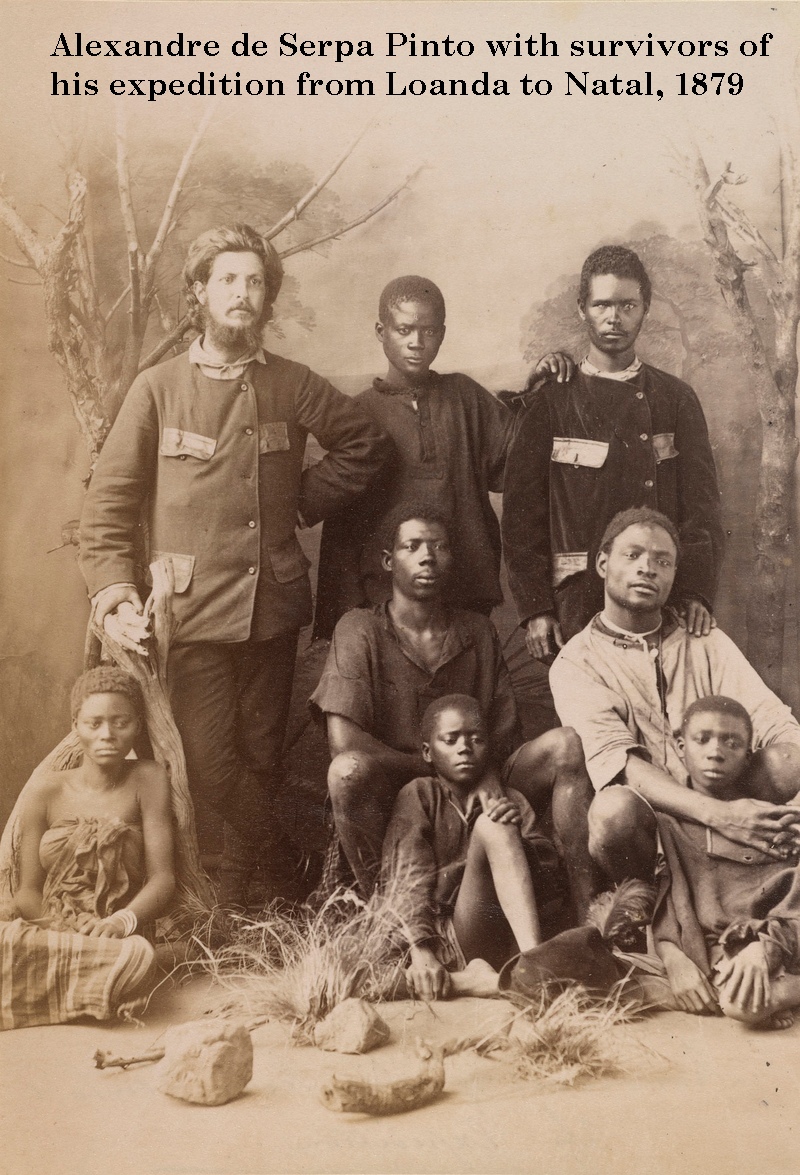

The Portuguese continued to protect their interests. Alexandre de Serpa Pinto “Serpa” was sent from Portugal as Battalion Commander in 1864 after rising through the ranks.  In 1869 he took part in suppressing tribes in revolt around the lower Zambezi. Also in that year he explored the Zambezi River. Eight years later he led an expedition from Benguela, Portuguese Angola, into the basins of the Congo and Zambezi rivers. In 1877, he and Lieutenant Commander Capelo and Lieutenant Ivens, both of the Portuguese navy, were sent independently to explore the southern African interior. Serpa Pinto reached Lealui, the Barotse capital, on the Zambezi, across to the Livingstone Falls, then down to Pretoria and on to Natal. Ten years later he confronted the British in the Shirè Highlands, Nyasaland.

In 1869 he took part in suppressing tribes in revolt around the lower Zambezi. Also in that year he explored the Zambezi River. Eight years later he led an expedition from Benguela, Portuguese Angola, into the basins of the Congo and Zambezi rivers. In 1877, he and Lieutenant Commander Capelo and Lieutenant Ivens, both of the Portuguese navy, were sent independently to explore the southern African interior. Serpa Pinto reached Lealui, the Barotse capital, on the Zambezi, across to the Livingstone Falls, then down to Pretoria and on to Natal. Ten years later he confronted the British in the Shirè Highlands, Nyasaland.

Most of the trading settlements were set up by outcasts from Portuguese society – political offenders and also criminals whose punishment was to be banished to the unhealthy African coast. In Mozambique, the prazo holders, who had dominated the Zambezi area - the central zone of Mozambique - from the 16th to 19th centuries, played a major role in the organized resistance against Portuguese occupation. The prazeiros had accumulated their wealth in the slave and ivory trades, but had also obtained land titles 'prazos da coroa'. The prazeiros used private slave soldiers 'chikunda' to secure their property and collect taxes. Originally the prazeiros were to act as delegates of the Portuguese Crown, but after centuries of intermarriage because of the absence of women of their own kind they developed a degree of autonomy and mixed race identity that turned them into “the chiefs of the newly emerging African peoples”.

David Livingstone encountered them in the middle of the nineteenth century in the form of “Black Portuguese”. He considered that they were of low moral standard and detested by the native tribes of the interior.

On the other hand, Livingstone and other travellers paid frequent tribute to the kindness and hospitality of the Portuguese officials and administrators but they did little to restrain the nefarious activities of the mixed race that brought Portugal’s name into disrepute.

Portugal was fanatically jealous of her past associations in parts of the interior. When Baines was attempting to obtain the concession for Britain from Lobengula, the Ndebele chief at modern day Bulawayo; the Portuguese protested in 1870 and lost no opportunity to proclaim their country’s title to present day Rhodesia, which they based on a 'concession' alleged to have been granted by the Monomotapa to the Portuguese expeditions of the 16th century. The Governor of Quilimane who was also the head of the Portuguese diplomatic mission to the Transvaal Republic wrote to Thomas Baines from Potchefstroom on 11th July, 1870. In the name of “His Majesty the King, my August Sovereign”, he warned that ''the territory north of the Limpopo in which the company is at present conducting its operations belongs to the Crown of Portugal and is an integral part of the District of Sofala in the Province of Mozambique''. No contracts or cessions of land or of any other kind made between Baines and any native chief, he said, could have any validity without the previous sanction of His Most Faithful Majesty.

Baines's reply was courteous and restrained ''Though I am aware of the achievements of your ancient voyagers and honour their memories for the courage and perseverance they displayed, I do not know either from history or tradition or from researches here that the Portuguese ever colonized this country or held such possession of it as to give them a territorial right, or that it was ever inhabited by more than a few widely scattered and solitary individuals who apparently built houses where they settled for purposes of trade in the vicinity of native tribes, an act which would give them no greater right to the country than might be acquired by men of other nations who do the same. Even these have long been abandoned and for forty or fifty years no Portuguese subject has possessed a homestead here, a period quite sufficient to constitute an abandonment of claim if ever the Portuguese nation ever possessed any."

This argument made no impression on the Portuguese. They viewed the events of the next twenty years with growing disquiet - the activities of Cecil Rhodes, the grant of the Charter for the occupation of Mashonaland and the consolidation of the British claim to Nyasaland through the broadening influence of the Scottish and English Missions.

The Berlin Conference of 1884 addressed the territorial issue.

In 1885, immediately after the Berlin conference, the Foreign Ministry in Lisbon circulated the so called ‘Mapa corderosa’ with Portugal’s claims in Central Africa. According to the Portuguese government these claims were based on prior discovery. Yet, the eventual partition of territory became a matter of international diplomacy. After a series of negotiations and movement of troops in present day Manicaland, Lord Salisbury sent an ultimatum to the Portuguese government in 1890, demanding the withdrawal of the Portuguese troops from the areas where Portuguese and British interests overlapped. This ultimatum set the stage for the Anglo-Portuguese treaty of 1891. Portugal retained some of its possessions in sub-Saharan Africa - as well as some smaller colonial enclaves in Asia (e.g. Timor, Macau, Goa) – but it required both British consent and military assistance to sustain its claims. The northern frontier, with German East Africa, was amicably agreed upon in 1894 so the region known as Portuguese East Africa had a clearly defined shape on European maps.

Details of the physical conflicts between Britain and Portugal along the Rhodesian border in Manicaland and along the Nyasaland border at the beginning of the Shire Highlands is given in detail in the following sections on this page.

In the meanwhile the Portuguese lacked the resources to develop the areas that they claimed in Mozambique and they leased out territories to European (especially British) companies. The central regions of Manica and Sofala were handed over to large concession companies such as the ‘Companhia de Mocambique’ and ‘Companhia de Zambezia’. Attempts to develop cotton and sugar plantations and a textile industry were only partially successful and the colony was heavily dependent on remittances by migrant workers and transit goods (a railway line connecting Lourenço Marques to the goldfield in the Transvaal Republic had been built in 1886).

Beira, the city on the Indian Ocean, became a commercial centre beginning in 1891 as the terminus of a railroad into the interior. Subsequently this port handled the foreign trade of Congo (Kinshasa), Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Zambia, and Malawi as well as of Mozambique.

Portugal conflict with Britain along the Rhodesian border

Portuguese explorers like Paiva d' Andrade and Serpa Pinto tried to awaken interest in Africa, but in spite of their efforts little attempt was made to develop the resources of the inland regions. The Portuguese did not populate their colonies with their own people, introduce their own culture, overcome influences among the natives, and build towns or roads or schools. A semblance of law and order was maintained by despotic methods, characterised by periodical reigns of terror to subdue recalcitrants. In short, the Portuguese occupation of South-East Africa could hardly be considered 'effective' in the sense recognised by international law as per the Berlin Conference of 1884.

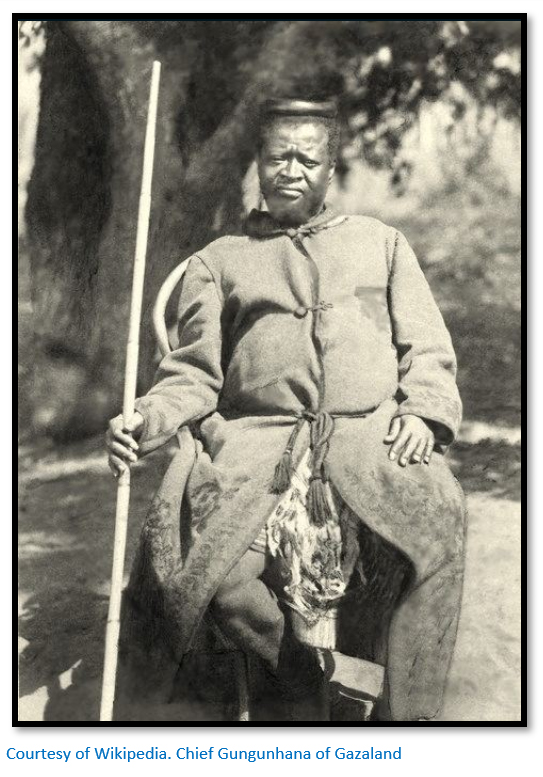

Yet Portugal was fanatically jealous of the interior. The designs of Rhodes perturbed her, the granting of the Concession by Lobengula increased her anxiety, and the start of the Column to occupy Mashonaland alarmed her. The Portuguese believed that they had a definite claim over both Mashonaland and Manicaland as the result of certain alleged "rights" granted to them by Gungunyana, king of Gazaland, the country lying along the eastern seaboard between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers, who, it was maintained, had sworn obedience to the King of Portugal in 1885. Like most of their claims, their ownership was based on doubtful documentary evidence, and the king later repudiated having accepted Portuguese authority at all.

Gungunyana's sway over Manicaland and the eastern portion of Mashonaland was similar  to that of Lobengula over the western portion of Mashonaland. The history of his tribe, the Shangaans, also was somewhat similar to that of the Matabele. Both hailed from the same stock, the Zulus, and both had broken away from the parent nation at about the same time. While Mziligazi had fled north-west, so Shangane and his followers had migrated north-east and, leaving the same trail of death and destruction behind them, settled in the country between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers. There they adopted the typical Zulu methods to establish their supremacy - a ruthless campaign of extermination against all the other, and much weaker, tribes in the country, and the absorption of the young men and women into their own tribe, with the same result as on the Matabele - the vigorous blood of their Zulu origin debased and watered down by the inferior blood of the people they conquered. Compared with their predecessors, the Shangaans were considered to be degenerate.

to that of Lobengula over the western portion of Mashonaland. The history of his tribe, the Shangaans, also was somewhat similar to that of the Matabele. Both hailed from the same stock, the Zulus, and both had broken away from the parent nation at about the same time. While Mziligazi had fled north-west, so Shangane and his followers had migrated north-east and, leaving the same trail of death and destruction behind them, settled in the country between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers. There they adopted the typical Zulu methods to establish their supremacy - a ruthless campaign of extermination against all the other, and much weaker, tribes in the country, and the absorption of the young men and women into their own tribe, with the same result as on the Matabele - the vigorous blood of their Zulu origin debased and watered down by the inferior blood of the people they conquered. Compared with their predecessors, the Shangaans were considered to be degenerate.

Umtasa, the most important chief in the Manica country, was considered by Gungunyana and the Portuguese to be a vassal of the former. Since Gungunyana was considered a vassal of Portugal, it followed that any rights conferred by the king of Gazaland must also apply to Manicaland. But Rhodes thought differently. Umtasa did not admit being a vassal of Gungunyana, or anyone else, and Rhodes regarded him as a paramount chief so to be completely independent. No rights could be claimed over Manicaland unless they had been granted by Umtasa himself, and there was no evidence to show that he had ever entered directly into an arrangement with the Portuguese.

It was therefore important that the Chartered Company, to support the concession obtained from Lobengula (the rights under which stopped short of Manicaland), should obtain a concession from Umtasa to consolidate its authority over the whole of the Mashonaland plateau before the Portuguese brought pressure to bear on him.

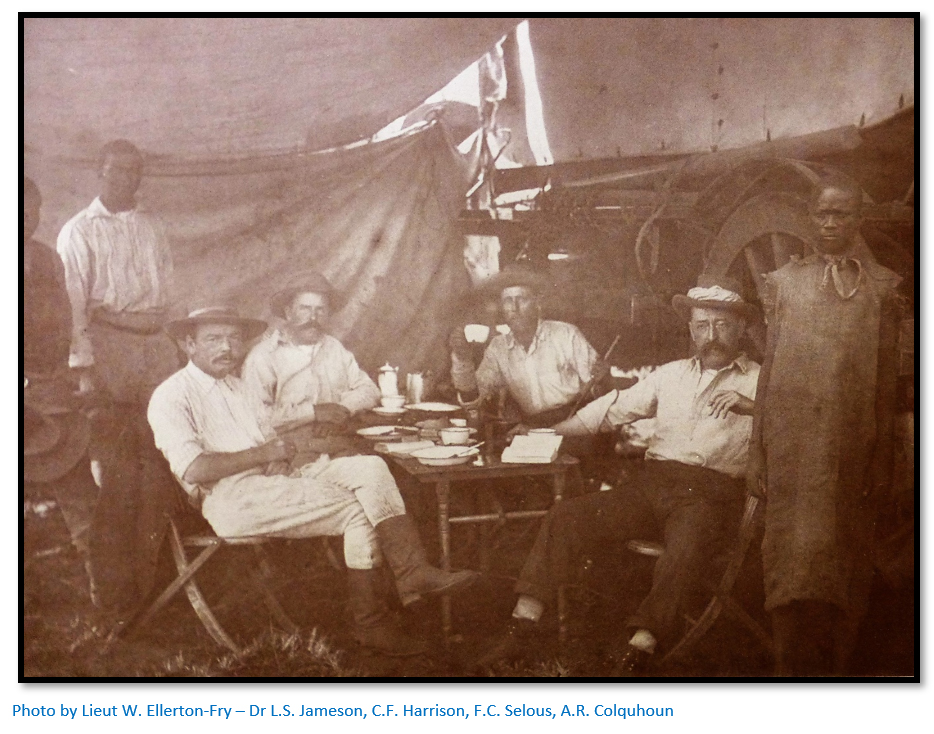

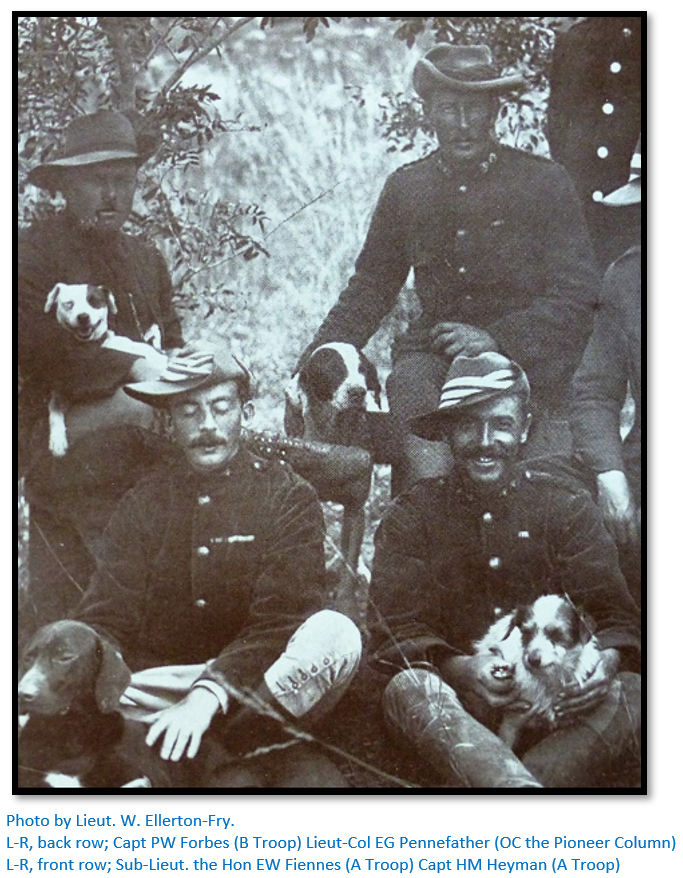

When the Pioneer Column had reached the plains 160 kilometres after leaving Fort Victoria, this was the nearest point to Umtasa’s kraal and it was considered to be safe enough to leave the Column. Dr Jameson, Colquhoun, Selous, Harrison his secretary and an escort of a dozen men hastened east across country.

Three days after setting out, while attempting to jump over a fallen tree, Dr Jameson’s horse stumbled and threw him and this broke two ribs. He insisted on Colquhoun and Selous going on to Umtasa with most of the escort. Dr Jameson was carried in a litter by natives from a nearby kraal until reaching the Pioneer Column that was constructing the fort at Charter.

On September 14th, 1890, Colquhoun entered into a treaty with Umtasa after the chief  had solemnly assured him that no treaty of any sort had been concluded, or arrangement of any kind made, with the Portuguese. He granted to the Chartered Company all the mineral rights in his country, and agreed that no one could possess land in Manicaland without the written consent of the Company. In return; Colquhoun, on behalf of the Company, promised him protection against his enemies, the payment of annual subsidies, and to establish schools.

had solemnly assured him that no treaty of any sort had been concluded, or arrangement of any kind made, with the Portuguese. He granted to the Chartered Company all the mineral rights in his country, and agreed that no one could possess land in Manicaland without the written consent of the Company. In return; Colquhoun, on behalf of the Company, promised him protection against his enemies, the payment of annual subsidies, and to establish schools.

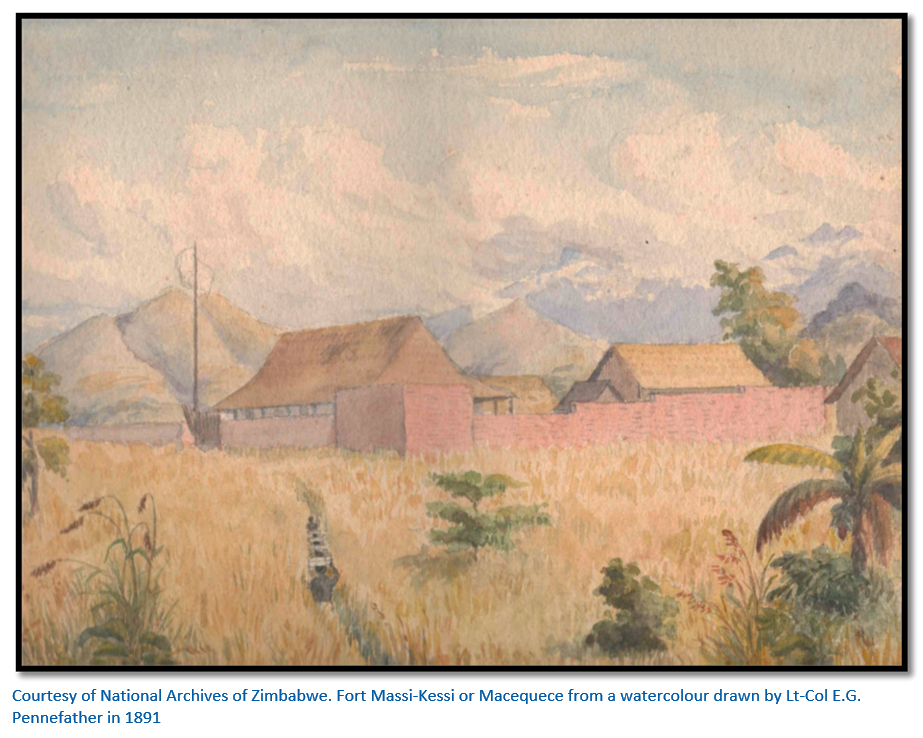

News of the treaty drew an indignant protest from Baron Rezende, the representative of the Mozambique Company ('Companhia de Mocambique' a chartered company formed to exploit the Portuguese possessions in a manner that is similar to the British South Africa Company) residing at Macequece, a few days' march from Umtasa's kraal. The letter, delivered by two Portuguese officers, protested against the occupation of Mashonaland and the ''extraction by force or menace'' of a treaty from Umtasa who (stated the Baron) had already signified his allegiance to Portugal. Colquhoun replied that the occupation of Mashonaland had been carried out strictly in accordance with instructions sanctioned by the High Commissioner, Sir Henry Loch. As regards the treaty, he pointed out that an escort of a dozen men could hardly be considered to constitute "force or menace",and that the treaty had been signed in the presence of Umtasa and his indunas, in the full light of day. It soon became apparent that Portugal was determined to enforce her ''ancient rights'' over the territory. In the eyes of the British, the ''occupation'' claim of the Portuguese was ludicrous. It was based mainly on the visits paid by an armed expedition in the autumn of 1889, to the headmen of half a dozen Mashona kraals in the northern part of the country. At its head had marched Colonel Paiva d'Andrade one of the principal agents of the Mozambique Company, in whom the fire of exploration and adventure still burned, and a half caste Goanese, named Manuel Antonio de Souza, but generally called 'Gouveia' - after the place in the Gorongoza Province where he had his headquarters - Portugal's most valued servant in that part of the continent. They had distributed Portuguese flags and guns with a generous hand, and apparently considered that their liberality bound the headmen and their subjects to the allegiance of Portugal for all time.

With the presentation of the guns and flags the ''effectiveness'' of the occupation ended. In Manicaland itself, the only European residents were the Baron de Rezende, one or two French engineers engaged in surveying the route for a railway which the Portuguese were said to be contemplating, and a few British and American prospectors who had obtained minor gold concessions from the Mozambique Company. From Manicaland to the coast the entire Portuguese population consisted of a few men at Neves Ferreira, about seventy miles from the mouth of the Pungwe river, and at Beira, at the mouth of the river. Not all of them were of pure Portuguese blood; most of those who occupied “official'' positions and conducted the trading stations had a good proportion of native blood in their veins.

Gouveia held the military  rank of a general and had been appointed by the Portuguese Government as military governor 'capitao mor' of the Gorongoza Province. He had been granted exclusive rights over the province in return for a definite contribution to the national treasury, and he obtained his revenue by a system of brutal extortion from the natives under his ''care.'' He had a certain amount of courage and cunning that had drawn around him a force of several thousand desperadoes with whose aid he terrorised a large area of country. His name was held in fear from Tete to the Sabi; he raided and plundered all chiefs who showed the least sign of resistance to him, and he monopolised the trade of the country over which he held sway.

rank of a general and had been appointed by the Portuguese Government as military governor 'capitao mor' of the Gorongoza Province. He had been granted exclusive rights over the province in return for a definite contribution to the national treasury, and he obtained his revenue by a system of brutal extortion from the natives under his ''care.'' He had a certain amount of courage and cunning that had drawn around him a force of several thousand desperadoes with whose aid he terrorised a large area of country. His name was held in fear from Tete to the Sabi; he raided and plundered all chiefs who showed the least sign of resistance to him, and he monopolised the trade of the country over which he held sway.

His harem was composed of young girls selected from native kraals, and slavery was not the least of his villainies. The mere fact that Gouveia perpetrated his outrages without interference by the Portuguese Government or the Mozambique Company is sufficient condemnation of the Portuguese title to '' beneficial” occupation. In fact, the Portuguese had found him and his force of savages useful in keeping recalcitrant tribes in order. Subsidised by an annual payment and supplied with arms, Gouveia and his raiders represented practically the only military force that they possessed in the interior.

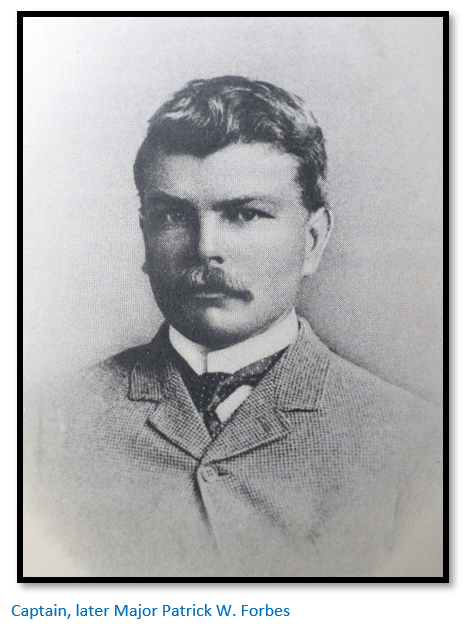

Having signed his treaty with the British, Umtasa began to get nervous about possible retaliation on the part of the Portuguese. He sent a message to Colquhoun asking for protection, and Captain Patrick W Forbes and a small patrol took to the road that had recently been opened by Selous from Salisbury to Umtasa's kraal. He went on a momentous mission, for he had instructions to occupy as much territory under Umtasa's concession as possible and to try to secure further afield. This was because Portugal's claims to the country were in the melting pot as a result of political manoeuvres in the Cortes, which had refused to ratify an agreement with England. Portugal had sovereignty over Manicaland and Gazaland and fixed the Sabi river as the eastern limit of the Chartered Company's sphere. Rhodes determined to take advantage of the confusion to bring as much country within his domain as possible, and to justify his actions afterwards.

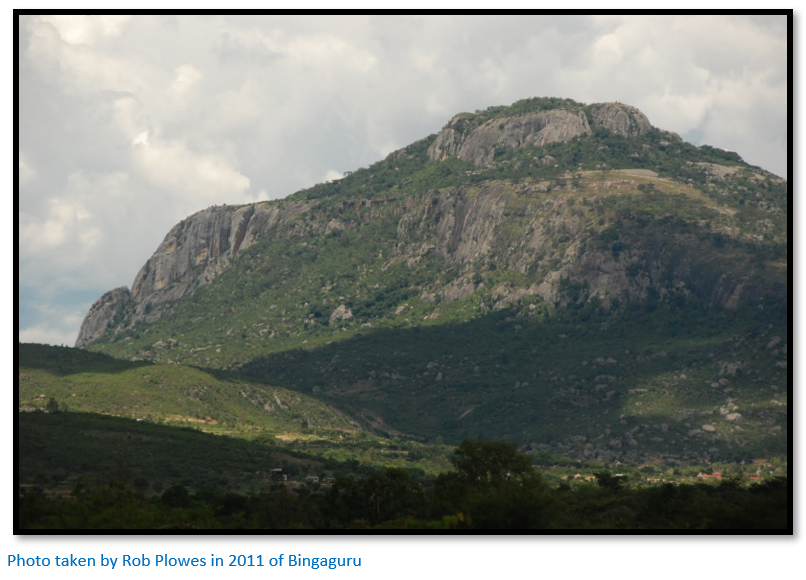

Forbes and his patrol arrived at Umtasa's kraal on 5th November, 1890. The kraal was situated at the top of a pass in the mountains protected from below by sheer masses of rock and from above by a wall of granite 300 feet high. The ground sloped sharply from the kraal for a considerable distance to a river below where Forbes took up his position.

He found Umtasa restless and uneasy. Half a dozen English and American miners who had gathered at the kraal for a meeting with Andrade told him that the Colonel had publicly threatened to drive the English out of Mashonaland unless they recognised Portuguese authority, and to destroy all the British South Africa Company's forts. He had also stated that he had a force of between three hundred and four hundred blacks ready to go anywhere at any time and that he could put Gungunyana's Shangaans against the '' poor Pioneers.'' In fact, said the miners, they had been called together to hear Umtasa declare that he had formally ceded Manicaland to Gouveia on behalf of Portugal twenty years before. When Forbes learned from the natives that a strong force under Andrade and Gouveia was on its way to deal with him he sent a messenger to Salisbury for reinforcements.

Unknown to Forbes, however, Umtasa was playing a double game. His preference for the British was based solely on the probability that they would prove to be stronger than the Portuguese, but, until he was definitely assured on the point, he considered that his wisest course would be to profess allegiance to both sides, and then declare himself on the side of the victor in the inevitable conflict. Accordingly he sent three head of cattle as a present to Andrade, accompanied by a declaration of loyalty. Andrade received them at Macequece, where he was busy with Rezende with regard to mining regulations.

Forbes considered that his presence at Macequece constituted a danger to Umtasa and threatened the peace of Mashonaland. He sent Lieutenant M D Graham with a letter to Andrade stating that since the occupation of the country by the British South Africa Company's forces he (Andrade) had conducted an armed force into British territory and that he must leave at once. Andrade read the letter with contempt, and did not reply. Instead, he and Gouveia set out for Umtasa's stronghold.

They took different routes, and Gouveia reached the kraal on 9th November, followed a few days later by Andrade and Baron Rezende. Forbes and his men were camped in a ravine about two miles away and the only Europeans at the kraal itself when the Portuguese arrived were the English and American concessionnaires, a South African Dutchman, a French engineer and a number of Spanish miners. Forbes had a native spy in Umtasa's kraal to keep him informed of developments.

Two days after his arrival, Andrade proceeded to settle matters with Umtasa. The chief denied having signed any paper placed before him by the British. '' I would have cut my hand off first,'' he declared in pious indignation.

In the meantime, Forbes and his men had stayed quietly in their camp, waiting for the news which the spy periodically brought. The British force consisted of Forbes, Graham, Lieutenant Shepstone, Denis Doyle who was acting as interpreter, a newspaper correspondent named Beaman, ten troopers and four former members of the Pioneer Column, who had wandered down in search of excitement. The spy told Forbes that Andrade and Gouveia had with them one hundred and fifty natives armed with rifles.

Forbes could not take the offensive with so small a force but at breakfast time on the morning of Andrade's meeting with Umtasa, his patrol was strengthened by the arrival of Captain Hoste and Lieutenant Tyndale-Biscoe, former officers of the Pioneer Column, with despatches. Still he waited, wondering when his reinforcements would arrive.

At about one o'clock the spy rushed down the hill from the kraal to report that Andrade was trying to get Umtasa's people to attack them. The position was beginning to look serious. Just at that moment, however, an outpost rode in with the welcome news that Lieutenant the Hon. Eustace Fiennes and fifteen men were in sight. The reinforcements had arrived just in time.

After a hurried conference they decided to capture Andrade and his companions while they were together in a bunch. Fiennes, Biscoe and the fifteen men were ordered to disperse Gouveia's '' army'' which was standing along a ridge between the camp and kraal, without bloodshed, if possible. Graham, who was ill with fever, and the four former Pioneers, were told to look after the camp, and the rest of the force made up the steep hill for the kraal.

Their approach was not observed, for the entire population was inside the high palisade absorbed in a very interesting ceremony. The Portuguese flag had been hoisted on a pole in the centre of the kraal and they were crowded thickly round it, listening to a resounding speech by Andrade. The Portuguese had, apparently, dismissed the possibility of interference, for no guards had been posted, and Forbes, with Hoste, Doyle and his eight men, entered the enclosure unmolested.

The gathering was just breaking up as they arrived. The English and American miners were walking away, and Andrade and Gouveia had entered the chief's hut to celebrate his declaration of loyalty. Rezende had hung back for a moment and he was the first to be arrested.

Ignoring the shouts of the excited natives, who were all carrying assegais and knobkerries, Forbes approached the chief's hut. The cries of ''Ingelsi '' (the English) drew Andrade and Gouveia to the doorway, where they were confronted by Forbes and half a dozen supporters. Andrade drew himself up ''I am Colonel Andrade” he said proudly. '' What do you want here?''

Forbes replied: '' I arrest you for intriguing and conspiring with natives in British territory.''

A menacing situation had in the meantime arisen, however. Umtasa's natives had begun to fear that the troopers had designs on their chief also, and angry shouts rose from them. Gripping their spears and sticks, they began to surge towards the little group of Europeans. But Doyle and Umtasa's head induna (who had no love for the Portuguese) got in front of them, and, shouting at the top of their voices, told them that the English were their friends and had come to deliver them from the Portuguese. The mob quietened down a little and paused uncertainly.

In the meantime Forbes and his men had been making for a gap in the palisade and as the natives paused they pushed their prisoners through. When they were all outside Forbes turned to Hoste. “Take the prisoners to the camp, and if they attempt to escape don't hesitate to shoot. If they get loose they'll raise the whole country against us.” Then he turned back to have a talk to Umtasa. In spite of the threat they had plainly heard, Hoste's prisoners walked unwillingly. Andrade, a neat, dapper little figure, carried himself proudly, his whole bearing expressive of contempt for his captors. His flashing eyes and grimly set mouth were the only outward indications of the anger that seethed within him at the indignity of his position - an officer of the Portuguese army tricked by a scroundrel of a native chief and now held captive by a few men, who in their patched and ragged clothing, looked more like a gang of brigands than the representatives of the British South Africa Company.

Gouveia, a tall, heavy man of about fifty five years of age walked hurriedly. His small, beady eyes rolled uneasily, and his thick lips trembled with apprehension. Baron Rezende gave no clue to his feelings except for the proudly held head.

Hoste placed two sentries at the door of the hut they occupied and took his ''guests” inside. On the bed lay Max Graham, who had delivered Colquhoun's letter to Andrade at Macequece, but Andrade's only greeting was a cold stare. The atmosphere was one of icy hostility. To infuse it with a little of the warmth of goodwill, Hoste produced a half bottle of whiskey and invited them to enjoy what limited hospitality he could offer. Andrade and Rezende haughtily refused, but Gouveia, greatly relieved at this sign of cordiality, accepted with alacrity. Gouveia, also, was the only one of the trio who would accept a cigarette. Hoste had abandoned in despair all attempts to open a conversation when Lieutenant Fiennes, Tyndale-Biscoe and the troopers who had successfully disarmed the Portuguese followers and chased them away, returned to the camp. The first thing they saw as they passed the Portuguese camp close to the kraal on their return was the midday meal laid out in a large tent, and, considering it as the spoils of war, they immediately ate it. Biscoe, also, had captured their drum.

When Forbes arrived Andrade jumped from the box on which he had been sitting, every hair in his trim beard bristling. '' Captain Forbes,'' he exclaimed, '' you are one dam' rascal. In future, when your name is mentioned, the very dogs in the street will bark.''

Astonished at the vehemence of the outburst, Forbes stared at the Colonel, a dull flush mounting to the roots of his hair. But he kept a grip on his temper, and when he had regained full control of himself, replied in a soothing voice: “Sit down, señor, and don’t make a fuss. We'll have some dinner directly, and then perhaps you will feel a little better.”

A meal was soon prepared and the food brought into the hut. Anxious to cause them as little inconvenience as possible, Forbes and two of his officers handed their mess traps to the prisoners, and were consequently obliged to use their fingers. Forbes took the precaution of having an ear kept on the captives' conversation during the meal, and instructed Corporal Morier, son of the British Consul at Lisbon and a fluent Portuguese linguist, to wait at table. But their consideration in the matter of mess traps was apparently misunderstood, for the first remark that Andrade made to Rezende as they sat down was: '' This is like feeding in a robbers' cavern. Look at the disgusting brutes eating with their fingers! ''

The next day Andrade and Gouveia were sent off to Salisbury under escort, while Baron Rezende was kept at the kraal pending instructions in regard to his immediate future. Andrade obtained no satisfaction from Colquhoun when he interviewed him at Salisbury, and he and Gouveia continued their journey to Lisbon by way of Cape Town. Although they were in fact prisoners, Rhodes had given orders that they were to be treated with the utmost courtesy and consideration, and that in no way were they to be made to feel that they actually were prisoners, but more persons whose presence in the country was not desirable. Andrade, however, was determined to give Rhodes no satisfaction on the point. Throughout his journey to the Cape he maintained an attitude of injured dignity and stiff-necked pride that irritated the Chartered Company’s chief officials exceedingly.

Only when he was actually on the road with his ' gaoler," Corporal Mundell, did he relax. Mundell found him a cultured, polished gentleman of high intellectual attainments and with considerable charm of manner. At the beginning of their trip, however, he was remarkably obstinate on the point of his '' status." The wagon had been well packed with everything available to relieve the tedium of travel. Among the provisions was a case of champagne. On the second day from Salisbury, after a long and tiring trek which left their throats parched and dust-laden, Mundell suggested that a bottle of champagne would brighten the outlook. But Andrade drew himself up, and replied: '' Thank you, but I do not think it would be correct for me, a prisoner, to drink champagne with my guard.'' Gouveia's attitude, needless to say, was entirely different.

At Charter they replenished their stores and purchased several tins of green peas and Oxford sausages, which figured largely on the daily menu until they reached Tuli, when they were all heartily sick of them. The wagon was outspanned at the foot of the hill below the fort; but Andrade refused to accept any hospitality from the Police officers or administrative officials. He declined the offer of a large airy hut in which to sleep, and insisted on remaining at the wagon.

Soon after their arrival Dr Jameson, who had been visiting Rhodes, appeared on the scene after a hurried trip from Kimberley at the request of his leader, who had become alarmed at the developments in Manicaland. Mundell introduced the two men, both of them outstanding in their different ways, each anxious for the expansion of his own country in Africa. For a few minutes they regarded each other with interest on the part of Jameson and with a cool reserve on that of Andrade. At first he refused to have anything to do with Jameson, but yielded to the doctor's tact and charm of manner. For nearly half an hour they talked. The Portuguese seemed to monopolise the conversation and his voice, raised high in indignation over his arrest and the occupation of the country which he considered belonged to Portugal, was audible some distance away.

A day or two later Mundell and his prisoners continued their journey down the long, dusty length of Bechuanaland to the railhead at Kimberley. Here they were met by Dr Rutherfoord Harris, the South African secretary of the Chartered Company, who, in an endeavour to appease Andrade, had arranged for an elaborate breakfast at a private dining room at the station. Andrade refused point blank to have anything to do with either Dr Harris or his breakfast, and after bidding Mundell an emotional farewell (the two had become friends) he boarded the train for Cape Town.

As soon as Andrade and Gouveia had left the kraal for Salisbury, Forbes decided that the first thing to do was to get Umtasa down to the camp to explain his recent professions of loyalty to the Portuguese. Colquhoun, the Administrator, had sent a present of blankets, lengths of calico, beads and other trinkets dear to the heart of the native, to be given Umtasa in recognition of his allegiance to the Company. Forbes decided to withhold the presentation until after the interview.

Next day Umtasa descended the hill, supported by about a dozen indunas and a large  crowd of his people. Forbes paraded his little force and made the best show he could. Umtasa, dressed in an ancient and very ragged mackintosh, arrived in an advanced state of intoxication and was obviously almost demented with fear. An attendant placed a stool in position, but Umtasa was so drunk that he had to be lowered on to it by two of his indunas, who throughout the interview stood close behind him to prevent his rolling off. When the natives saw that their chief had accomplished the feat without disaster they began to clap their hands in salutation although to the ears of the troopers it sounded unmistakably like applause as though success did not always attend Umtasa's attempts to sit on his stool.

crowd of his people. Forbes paraded his little force and made the best show he could. Umtasa, dressed in an ancient and very ragged mackintosh, arrived in an advanced state of intoxication and was obviously almost demented with fear. An attendant placed a stool in position, but Umtasa was so drunk that he had to be lowered on to it by two of his indunas, who throughout the interview stood close behind him to prevent his rolling off. When the natives saw that their chief had accomplished the feat without disaster they began to clap their hands in salutation although to the ears of the troopers it sounded unmistakably like applause as though success did not always attend Umtasa's attempts to sit on his stool.

With Doyle as interpreter, Forbes administered a severe rebuke, and impressed on the chief the importance which the British attached to undivided loyalty and the firmness with which they dealt with acts of treason. He was answered principally by the head induna, an elderly native of more than average intelligence, while Umtasa, with his eyes on the ground, nodded his head in befuddled agreement. The talk ended, Forbes handed over the Administrator’s gifts and, to the accompaniment of more hand clapping, the chief and his councillors returned to the kraal.

Forbes’s next move was to capture the fort at Macequece, for with that in Portuguese hands so close to British territory, Mashonaland could not be considered safe. They broke up their camp and, accompanied by Baron Rezende, started off, taking with them a wagon which Fiennes had brought from Salisbury since there was no road and their path was barred by a high range of mountains, the wagon was more of a hindrance than a help, and on the third morning, when they found themselves only twenty miles away from the kraal, they left it among the hills. They hired some carriers from neighbouring villages and rode on for the fort.

Early in the afternoon they caught their first glimpse of its mud walls, with the flag of  Portugal fluttering over it. It looked somewhat like a farmhouse to which had been added a couple of bastions. That morning they had heard from native sources that a Portuguese regiment had moved into the fort a few days before, and the troopers found the task of approaching it a nerve racking business. Every moment they expected to hear the crash of cannon and the rattle of rifle fire, but the hot silence remained unbroken. They had only a few hundred yards to go when a messenger carrying a white flag came out to tell them that the garrison was prepared to capitulate. When they entered the fort they found that it was held by a corporal, a private soldier, and a motley crowd of about forty five Portuguese, French, Spanish and half-caste settlers.

Portugal fluttering over it. It looked somewhat like a farmhouse to which had been added a couple of bastions. That morning they had heard from native sources that a Portuguese regiment had moved into the fort a few days before, and the troopers found the task of approaching it a nerve racking business. Every moment they expected to hear the crash of cannon and the rattle of rifle fire, but the hot silence remained unbroken. They had only a few hundred yards to go when a messenger carrying a white flag came out to tell them that the garrison was prepared to capitulate. When they entered the fort they found that it was held by a corporal, a private soldier, and a motley crowd of about forty five Portuguese, French, Spanish and half-caste settlers.

Forbes hauled down the Portuguese flag and, as he detached it from the lanyard, remarked, “What on earth are we going to fly in its place? We must have colours of some sort.'' Hoste answered the question for him. Before leaving Salisbury he had had a feeling that a Union Jack might come in useful and had stuffed a flag into one of his wallets in place of a spare shirt. With the air of a conjurer he produced the familiar colours, and watched them unfold in the breeze. Their stay at the masthead of Macequece fort, however, was destined to be short lived.

Over a meal of bully beef, ship's biscuits and coffee, the conquerors held a conference to decide their next step. Remembering Rhodes's injunction to capture as much Portuguese territory as he could, Forbes made up his mind to make for the coast, particularly now that the babble of Portuguese military resistance had been so effectively pricked. Accordingly, next morning, accompanied by Doyle, Beauman, and less than a dozen troopers, he marched off to capture Beira, which he considered they should reach in a fortnight. They had to go on foot, with natives carrying their provisions, because the presence of tsetse fly in a large section of the country they had to traverse made animal transport impossible.

Hoste, with Tyndale-Biscoe and four men, was left in charge of Macequece and the surrounding district. His chief anxiety was the prisoners, who outnumbered his little band by ten to one. Baron Rezende and a French engineer named de Lambi cooperated, but the remaining forty were both sullen and antagonistic and Hoste was afraid that they might try to regain possession of the fort. During the day it was easy enough to keep an eye on them to prevent them from escaping, but it was a different matter at night. A lion which had been troubling the district for some days solved the difficulty for him. When the sun sank below the western hills he turned his prisoners out of the fort and made them huddle in the angle formed by one of the bastions and the wall. He placed a sentry on the wall and another at the gate of the fort. The lion did the rest, for the prisoners did not dare to attempt to escape while he was prowling about!

In the meantime Forbes was making rapid progress towards the coast, and in the first two days covered fifty miles. The trip was not without tragedy, however, for while the party was passing through some dense bush, Beauman, who had been walking in the rear, stopped to tie up his bootlace. Half an hour later his half-section, Fermanagh, became anxious at his absence and passed the word to Forbes, who at once turned back to look for him. They searched the bush in vain and eventually had to continue on their way. It was surmised that Beauman had been taken by a lion which had crossed the path in front of them a few minutes before he had stopped.

At Chimoio's kraal, which was just outside the fly belt, Forbes established a post station at which he left a couple of men to act as a connecting link between him and Macequece, and so with the authorities at Salisbury. Then he and the others travelled nearly a hundred miles through dense bush and tropical forest to the banks of the Pungwe river. All the Portuguese forts which they encountered on the way surrendered at the first sign of their approach, and their journey so far had been in the nature of a triumphal march.

They were on the point of embarking in canoes to sail down the Pungwe to capture Beira when a breathless trooper overtook them with a despatch from Colquhoun on behalf of Rhodes recalling them immediately. The events in Manicaland had resulted in a strongly worded protest by the Portuguese Government to the British Government, who in turn had instructed Rhodes to call his men back until an arrangement could be made between Portugal and England.

Had he not been recalled at the critical moment, there is little doubt that Forbes and his half dozen men would, have taken Beira in spite of its armed garrison, for the Portuguese had been thrown into the utmost confusion by the rapid march of events, and were thoroughly alarmed by the exaggerated reports of the British successes emanating from native sources. They, too, would have most probably surrendered on the appearance of the invaders. As it was, however, Forbes had to abandon his project. Macequece was declared the provisional boundary between Portuguese and British territory until a treaty could be concluded. It was accordingly restored to the Portuguese, and the Chartered Company's troops retired to Umtasa's kraal.

This only turned out to be a provisional agreement between England and Portugal. The withdrawal of the Chartered Company's troops from Macequece did not end matters as the most stirring act in this drama was yet to come. For a few months there was an uncertain peace, with the position aggravated by the Portuguese closing the Pungwe river to traffic between Mashonaland and the sea.

During the lull, the Company seized the opportunity to induce a number of prospectors and others in Mashonaland to 'drift' into Manicaland to comply with the essential of "effective occupation." Many of the men who had entered the country either with the Pioneer Column or immediately in its wake, were only too eager to try their luck in fields as yet largely untested and therefore full of promise. At Salisbury they were equipped with wagons, oxen, provisions and ammunition, and made their way into the new territory.

The incidents at Umtasa's kraal, however, had caused intense indignation in Portugal, whose national honour, it seemed, had been seriously slighted by the arrest of Colonel Andrade and Baron Rezende, and by the British occupation of country which she considered belonged to her. On his arrival in Lisbon, Colonel Andrade lost no time in thoroughly discrediting the actions of the Chartered Company's forces.

Andrade’s version roused the country to a high pitch of indignation and excitement particularly among the students that are always intensely patriotic. Hundreds of them flocked to the colours and enlisted in an expedition to avenge the insult to their national pride. They sailed from Lisbon early in 1891, determined to drive the British out of both Manicaland and Mashonaland. Nothing would stop their triumphal progress.

They arrived at Beira towards the end of February, and started off on their long and arduous march to Manicaland. They were badly organised and most of their officers were inexperienced youngsters with no knowledge of tropical conditions. Many of them were left behind at Beira ill with malaria. The others went up the Pungwe, and the further they advanced the fewer became their numbers. When they landed at Neves Ferreira and attempted to force their way through the tropical vegetation they found the fever, the marshes, the torpid atmosphere and the insufficiency of food and medical supplies too much for them. Before the onslaught of tropical Africa at her most inhospitable season, their patriotic fervour wilted. Hundreds of them dropped out and made their way back to the nearest outposts as best they could. There is something pathetic about this crowd of boys, inspired by the highest motives of patriotism, being subjected to trials far too severe for their physical stamina or moral strength. Those who managed to complete the journey took two months to traverse the country from Neves Ferreira to Macequece.

Colonel Pennefather, who was in charge of the Chartered Company's police forces, was visiting Manica towards the end of April when he learned from the natives that a large Portuguese force was advancing on Macequece. He was called away, however, by an urgent message which reached him at about the same time requiring his presence on the southern border, where a party of Boers was about to attempt to cross the Limpopo with the object of seizing the country. He left Captain (now Sir Melville) Heyman in charge of the small British force at Umtali, the little township which had been established among the hills in Manicaland near Umtasa's kraal.

On 6th May the Portuguese force reoccupied Macequece fort. Just before they arrived Heyman took up his position on Chua Hill, which overlooked the fort and guarded the approaches to Umtali, Umtasa's kraal and Mashonaland. His force consisted of thirty three dismounted policemen and fifteen, volunteers, former members of the Pioneer Column who had ''drifted” in as prospectors. They had no horses owing to the ravages of horse-sickness, and all their provisions and material had to be conveyed from Umtali by a contingent of native carriers. Their artillery consisted of only one seven pounder gun.

Three days after the Portuguese had arrived, Heyman and Morier, the interpreter, waving a white flag aloft walked over to the fort to ascertain the reason for the arrival of this force. Their interview with the commanding officer, Colonel Ferreira, who had already adopted the optimistic title of 'Governor of Manica' was brief, but momentous. Ferreira candidly informed them that he had come to drive the English out of Manica but was considerate enough to add that if Heyman would withdraw his men to the west of the Sabi river, which was beyond the Portuguese sphere, he would use his influence to open the Pungwe to British transport. Heyman's reply left Ferreira in no doubt as to his intentions; he would stay where he was.

The next day a deputation of Portuguese officers was seen walking towards them across the valley between the fort and Chua Hill. For a moment Heyman was puzzled. Ferreira already had his answer: nothing was to be gained from another interview. Then it occurred to him that the probable object of the impending visit was to ascertain the strength of his force. He was equal to the occasion. Quickly he ordered the majority of his men to duck down out of sight behind the rocks on the hill top, and to give a hint of their presence. He concealed the seven pounder under a heap of patrol tents, and told the rest of his men to lounge about in careless attitudes. When the Portuguese officers reached the top of the hill Heyman's little deception was complete. All they saw was one officer and a few nonchalant men. They were encouraged to repeat the order to get out of the country at once. Heyman's reply was a blunt refusal. For a few minutes the visitors lingered to dart a few curious glances around the camp and then, satisfied that the British force was negligible in numbers, armament and discipline, jubilantly returned to the fort.

The climax came next day when the Portuguese force consisting of about a hundred Europeans and three hundred native levies, emerged in two bodies and advanced on the hill. Heyman ordered his men to hold their fire until they were well within range. The enemy drew nearer and nearer, the silence broken only by the excited chattering of the natives. Then, when they were a bare five hundred metres away, Heyman gave the order and a hail of lead tore into the Portuguese ranks from all angles. Disconcerted, the attackers halted, and for a moment wavered. They had been told that they would meet only a few men, poorly equipped with arms, yet here they were being faced with a withering fire from a dozen points, indicating that the British force was a large one. The roar of the seven pounder as it belched a canister at them caused temporary havoc. A cannon! For a minute or two it seemed that they would flee in retreat, but the shouting voices of their officers rallied them, and they returned to the attack. As they advanced towards the foot of the hill they left the veld dotted with dead and wounded.

Although he was outnumbered to the extent of eight to one, Heyman had an important geographical advantage in his favour. He was on top of a hill, with his men protected by rocks which enabled them to rest their rifles and shoot with deadly accuracy. The Portuguese, on the other hand, were on open plain, easy targets for men as skilled with the rifle as his police and former Pioneers, and they had the added disadvantage of having to climb a hill and fire upwards, which spoiled the certainty of their aim. Already flustered by the size of the opposing force, the Portuguese were thrown still further out of gear by the insistent fire. As they panted across the plain and tried to mount the lower slopes of the hill, their shooting was wild, and their bullets flew harmlessly over the heads of the defenders. In the early stages of the battle the effectiveness of the seven pounder was reduced by a tree which curtailed its range· of fire and exposed its crew to the pot shots of a Portuguese sniper, who, however, did no damage beyond twice hitting the gun. The obstruction was removed by Trooper A Tullock, who went out with an axe and cut the tree down - a remarkably plucky action, for he was a clear target for anyone of the enemy who cared to take careful aim. A bullet struck the trunk just above his head as he stooped to swing the axe, but that was as close as they got to hitting him. After several minutes of frantic work, Tullock scampered back to cover as the tree toppled over and the seven pounder came into action again.

Although he was confident that, from the point of view of fighting ability, his force was  superior to that of the enemy, Heyman's main fear was that, with their greater numbers, the Portuguese might be able to surround the hill and attack him from the rear. This danger he circumvented by adopting another artful ruse. Standing in a prominent position so that the enemy officers could see him, he made a series of signals to an imaginary force in the hills, leading the Portuguese to think that reinforcements were not far away. Again his deception was effective; no attempt was made to surround him.

superior to that of the enemy, Heyman's main fear was that, with their greater numbers, the Portuguese might be able to surround the hill and attack him from the rear. This danger he circumvented by adopting another artful ruse. Standing in a prominent position so that the enemy officers could see him, he made a series of signals to an imaginary force in the hills, leading the Portuguese to think that reinforcements were not far away. Again his deception was effective; no attempt was made to surround him.

The fight went badly with the Portuguese. The native levies, accustomed to easy victories over tribes unversed in the arts of war, became dismayed at the resistance with which they were meeting. It was the first time they had come under gun fire, and as they saw their fellows dropping on all sides of them; they lost heart. The European troops fought with coolness and pluck, but the officers had a difficult task in keeping their black allies from fleeing headlong from the field. Three times they wavered and three times they obeyed the hoarse shouts of their leaders to continue the attack. But it could not last. After nearly two hours of fruitless effort to gain a footing on the hill, the natives turned and fled, and the European troops, who by this time had also lost heart, followed them back to the fort.

The casualties suffered by the Portuguese troops were heavy. On Heyman's side only one man was slightly wounded. One prisoner was taken, a little Portuguese whom Trooper Hay had run to earth in a donga. He was greatly relieved to find that the British did not shoot their prisoners on the spot.

The progress of the battle had been watched by crowds of natives from vantage points on the surrounding hills. Darkness fell shortly after the cessation of hostilities, and Heyman decided to leave the capture of the fort until next morning. Shortly after daylight one of the former Pioneers, Farrell, was dressed in Heyman's artillery uniform and sent with a white flag to the fort to offer the services of a doctor if required for the wounded. He found the fort empty of Portuguese, but alive with natives who had spent the night looting it. Under cover of the dark, the avengers of the insult to Portugal's honour had silently stolen away.

Heyman and his men soon evacuated the natives, and carefully inspected the fort. It was then that Heyman realised just how successful and fortunate his deception had been when he misled his visitors in regard to his strength, for he found eleven quick firing guns of the latest pattern. They had been left behind when the attack was launched in the belief that they would not be required against so small a force of British. Besides the guns they found the fort well stocked with foodstuffs, cooking utensils, boots, clothing, ammunition, rifles, dynamite, detonators, and spirits of wine. They also found several articles of feminine underwear. One of the troopers disobeyed orders by drinking a quantity of the spirits of wine, and paid the penalty by dying in delirium tremens.

Heyman ordered as many of the guns and as much of the foodstuffs as possible to be taken away. The rest was piled up into a large heap, saturated with the spirits of wine, and ignited. As they walked hastily away, the drama was brought to a fitting conclusion by a mighty roar, as the dynamite blew up. Where the fort of Macequece had been there was now a gaping crater.

When the first shots were fired in the battle, the native carriers had taken to their heels, and were now recounting their adventures in kraals many miles away. Heyman was consequently unable to press home his advantage by pursuing the flying Portuguese. In any case, even had the carriers stayed, it is doubtful whether he could have got very far, for many of the men had no boots and their clothing was in rags. The members of the Pioneer Column had been relieved of their kit at Mafeking, before the trek started, and had not yet received it; as a result they were left with only the clothes they stood in, which had suffered considerable wear and tear.

Three days after the battle Heyman sent Lieutenant Fiennes and six troopers to follow the fugitives. The patrol had not gone far when they met a party of officers from Ferreira's force returning under a flag of truce to ask permission to collect all the stores they had left behind at Macequece. Fiennes was naturally unable to accede to the request, and continued his pursuit. At Umluwan's kraal he found himself confronted by a stockaded fort occupied by Portuguese troops. Since he was not strong enough to attack the position, he formed a laager and waited for reinforcements, which had already been ordered from Salisbury, to reach him.

While he and his men were killing time watching the movements of the men in the fort, the Bishop of Mashonaland, Dr Knight-Bruce, arrived on his way from Beira to Salisbury with the news that Major Sapte, Military Secretary at Cape Town, was just behind with orders for the retirement of the Chartered Company's forces to the other side of Macequece. Fiennes decided to await the arrival of Major Sapte before raising his siege. Then he learned that a treaty defining the boundaries between the territories claimed by Rhodes and Portugal was on the point of being signed.

When the news was communicated to the officer in charge of the fort, he immediately invited his besiegers inside to celebrate it. And over a bottle of wine he blandly informed Fiennes that had he called upon him to surrender, he would immediately have done so, in spite of the fact that he had sixty men and four machine guns as against the half dozen ragged troopers behind Fiennes. The reputation gained by Heyman's little party at Macequece had proved to him that small numbers in a British force did not necessarily indicate weakness.

The rout of the Portuguese had a salutary effect in other quarters, also. The authorities at Beira desisted in their high handed attitude and treated intending passengers up the Pungwe with a welcome civility and courtesy. They had learned the lesson that the Pioneers of Rhodesia were not to be trifled with. The treaty signed in June closed an unpleasant chapter, and although it left Rhodesia without a port of her own, the drawback has to some extent been mitigated by the facilities which the Beira authorities grant to Rhodesia's trade.

Portugal conflict with Britain along Nyasaland-Mozambique border.

In 1879 the Portuguese government formally claimed the area south and east of the Ruo River (which currently forms the south eastern border of Malawi), and in 1882 occupied the lower Shire River valley as far as the Ruo. The Portuguese then attempted to negotiate British acceptance of their territorial claims, but the convening of the Berlin Conference (1884) ended these discussions. In 1884, Serpa Pinto was appointed as Portuguese consul in Zanzibar, and given the mission of exploring and remapping the region between Lake Nyasa and the coast from the Zambezi to the Rovuma River and securing the allegiance of the chiefs in that area.

The following year, he undertook an expedition with Lieutenant Augusto Cardoso as  his second in command. Serpa Pinto fell seriously ill and was carried to the coast, where he eventually recovered. Cardoso his twenty five year old lieutenant continued the exploration, visiting Lake Nyasa and the Shire Highlands, but failed to make any treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs in territories west of the Lake Malawi.

his second in command. Serpa Pinto fell seriously ill and was carried to the coast, where he eventually recovered. Cardoso his twenty five year old lieutenant continued the exploration, visiting Lake Nyasa and the Shire Highlands, but failed to make any treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs in territories west of the Lake Malawi.

Britain declined to accept the Portuguese claim that the Shire Highlands should be considered part of Portuguese East Africa, as it was not under their effective occupation. In order to prevent Portuguese occupation, the British government sent Henry Hamilton Johnston "Harry" as British consul to Mozambique and the Interior, with instructions to report on the extent of Portuguese rule in the Zambezi and Shire valleys and the vicinity, and to make conditional treaties with local rulers beyond Portuguese jurisdiction, to prevent them accepting protection from Portugal.

In 1888, the Portuguese government instructed its representatives in Portuguese East Africa to attempt to make treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs south east of Lake Malawi and in the Shire Highlands and an expedition organised under Antonio Cardoso, a former governor of Quelimane, set off in November 1888 for the lake.

A second expedition led by Serpa Pinto, who had been appointed governor of Mozambique,  moved up the Shire valley. Between them, these two expeditions made over 20 treaties with chiefs in what is now Malawi. Johnston sailed up the Shire in the African Lakes Company's stern wheeler, James Stevenson, until he encountered Serpa Pinto's camp near the confluence of the Shirè and Ruo rivers in August 1889. Pinto’s force comprised several European officers and a force of between two and three thousand native soldiers. Johnston was unable to accept the Major's assertion that his motive was merely scientific investigation. When Serpa Pinto asked for the good offices of the British in securing him an unmolested passage through the Makololo country along the Shire between the Ruo and Lake Nyasa, Johnston warned him that the size of his force was bound to arouse Makololo suspicions.

moved up the Shire valley. Between them, these two expeditions made over 20 treaties with chiefs in what is now Malawi. Johnston sailed up the Shire in the African Lakes Company's stern wheeler, James Stevenson, until he encountered Serpa Pinto's camp near the confluence of the Shirè and Ruo rivers in August 1889. Pinto’s force comprised several European officers and a force of between two and three thousand native soldiers. Johnston was unable to accept the Major's assertion that his motive was merely scientific investigation. When Serpa Pinto asked for the good offices of the British in securing him an unmolested passage through the Makololo country along the Shire between the Ruo and Lake Nyasa, Johnston warned him that the size of his force was bound to arouse Makololo suspicions.

He had reason to believe that Pinto's real purpose was to persuade the Yao chiefs of the region to join forces with him to conquer the Makololo, who had persistently refused to recognize Portuguese authority and were all the more obstinate now that they hoped the country would come under British protection. With this in mind, Johnston warned the Portuguese commander that if he caused any trouble north of the Ruo he (Johnston) would be compelled to take action to protect British interests.

After meeting with Pinto, Johnston sailed higher up the Shire to interview the powerful and aggressive Makololo chief Mlauri. Mlauri's people lived on the river bank at a point where the water was narrow and navigation difficult. Ever since Livingstone’s day their pleasure had been to hold passing steamers to ransom, demanding ''presents'' under threat of a shower of missiles from the high bank. Mlauri was intolerant of Europeans. He brusquely refused Johnston's offer of a treaty of friendship with the British, and at the same time stated that he intended to attack the Portuguese should they come within reach.